Happily Ever After

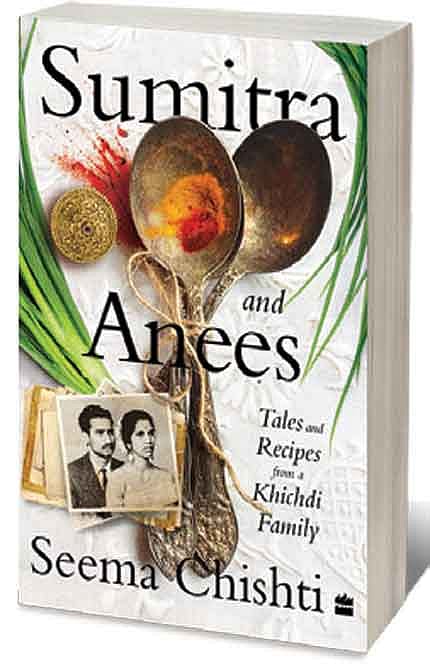

JOURNALIST SEEMA CHISHTI’S narration of an idyllic marriage between her parents, a Hindu woman from Mysore and a Syed Muslim from Deoria, is her argument against contemporary India’s drift towards state-backed surveillance and prevention of interfaith marriages and food practices. A child has the right to portray her deceased parents’ marriage in ways she likes. But when Chishti uses her parents’ marriage as evidence in a debate on consequential political and social issues, such as love jihad, then both the marriage and the merit in using it as an argument invite scrutiny.

Chishti is no Miriam Margolyes, the rare public figure who frequently refers to outré moments in her parents’ marriage—an alliance, as she says, was between a desperately shy man and a loud, fat, caustic woman. In Chishti’s book, professional ambitions bring Anees and Sumitra to Delhi in the sixties. They meet, marry, and live happily ever after. The story is almost like a family album, where pictures have been curated to construct an almost endless state of marital peace, if not bliss.

Chishti’s book fortifies an ironic literary pattern where blissful marriages exist far more in non-fiction than in fiction. The burden of portraying bleak marriages is then left to literature, where reality can be savoured without embarrassment for anyone. From Anna Karenina in the Russian literary classic to Man Booker winning Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, marriage has been consistently portrayed as a state of oppression for one or both partners. Strands of simmering discontent and uneasy equilibrium mark RK Narayan’s The Guide when the lovers start living together like a married couple. Ghachar Ghochar by Vivek Shanbhag, a recent story of covert violence in domesticity, tells us that even now illustrious Indian writers treat marriage with a certain amount of pessimism and wariness.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Nothing disturbs Sumitra’s marriage to Anees. The wife is older than her husband by eight years. Sumitra works as an economist at the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, rises to the position of director, and then moves to Jawaharlal Nehru University as a professor. Anees, the journalist, sees a steady if not spectacular career. It could not have been easy for the couple to nurture a marriage and a child while balancing demanding professional lives within a modest budget.

The intellectual accomplishments of Anees and Sumitra invite comparisons with a book on the married life of another distinguished couple—literary critic John Bayley and novelist Iris Murdoch. In Elegy for Iris, many anecdotes add up to what Bayley has described as “the manoeuvres and rivalries of intellect… the power struggles and surrenders of adult loving”. Unfortunately, Chishti either lacks these insights into her parents’ marriage or is diffident about sharing them. In the process, the story of this unusual marriage is robbed of its authenticity.

Chishti’s book has a political dimension. It is a constructive attempt to engage with the debate around love jihad. But is it a case of, to frame it bluntly, bringing out one’s umbrella in a hurricane?

Love jihad is a political reaction to perceived expansionism by Islam—a religion that sanctions and indeed mandates conversion—against Hinduism that has no scope for conversions. Castes are the building blocks of Hindu society. Hindutva knows Hinduism cannot convert because there is no guideline on which caste the converted will be assigned.

In this context, Hindutva views the twin acts of marriage and conversion as that of a foreign patriarchy that challenges its own patriarchy and, by extension, seeks to annihilate its society. The Hindutva argument against interfaith marriage, especially to a Muslim man, is not concerned with marital bliss or discord between the couple. A vivid account of one blissful marriage, however genuine, does little to address a portentous struggle for numerical, social, and political supremacy.