Floral Folios

THE 500-ACRE ROYAL Botanic Gardens, Kew, a mid-18th century establishment, which started as a private garden, has initiated the process of decolonising its research collection and re-analysing its responsibilities as a public museum. Recently, Kew published a 10-year manifesto for change that aims to redress historical wrongs, reach under-served populations, and conserve biodiversity.

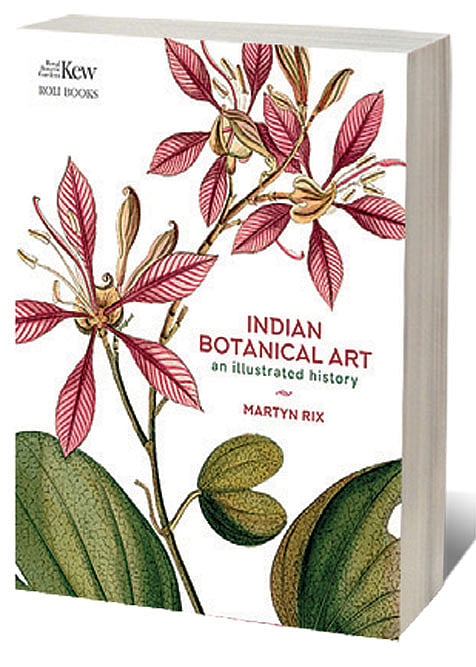

The 224-page book Indian Botanical Art written by Martyn Rix, a British botanist, collector, horticulturalist and author, can be seen as an extension of the garden’s efforts to rewrite history. Two hundred years since the first botanical paintings were sent by ship from India to Kew Gardens, this book will now return to the subcontinent for the first time as a printed archive.

Drawing from Kew and other collections, the book illustrates the relatively unknown stories of Indian botanical paintings from the times of the Mughals, starting from the rule of Babur to the East India Company, to the days of colonialism to current times.

The elaborate Introduction gives a detailed account of the growth of botanical art in India. The 18th century saw a resurgence of interest in the natural world and an almost obsessive attempt to list all species of plants and animals seen by European travellers to the Americas and Asia.

Young doctors who worked for the East India Company were trained in botany as part of their medical course. A few of them studied the unfamiliar plants they encountered, preserving dry specimens and commissioning local artists to make paintings of plants to keep an accurate record of the colours and details of the living plants.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Indian artists skilled in the Mughal, Rajasthani and other Indian miniature traditions were commissioned to make scientifically accurate paintings of plants, flowers and animals. Soon Indian rajas, European visitors and the Company made collections of paintings of traditional medicinal plants, ornamental flowers, birds and mammals that they kept in their private gardens. These were printed in many renowned botany journals of that time.

The book highlights several significant collections and more importantly, the forgotten Indian artists who made them. One of the earliest collections of scientific botanical paintings of Indian plants was commissioned by Lady Impey. At 25, she arrived in Calcutta with her husband and nine children to set up a beautiful garden in the eastern city and make a valuable collection of natural history paintings by employing three artists—Zain-al-Din, Bhawani Das and Ram Das—who described themselves as natives of Patna, and may have trained in the court of the Nawab of Bengal in Murshidabad and Patna. They initially concentrated on bird paintings, often, in the Chinese tradition, accompanied by, or perching on a flowering branch. But soon, they started creating paintings of plants, and for other collectors as well.

Botanist and collector Robert Wight planned to publish the drawings in India at affordable prices, to help other botanists identify the plants. His drawings are smaller than folio size and emphasise enlarged floral dissections. His artists were Rungiah and Govindoo. Together they made 4,000 paintings of which 1,445 were published. Rungiah was particularly good. He would place the plant on paper and draw the boundaries.

One of the most interesting yet succinct chapters is on botanical art in India today. It highlights the work of contemporary artists in this area. Thakur Ganga Singh (1895-1970) was one of the modern torchbearers of the art form. He was an artist at the Forest Research Institute in Dehradun for 30 years. In 1942 he was appointed as court painter of Yadavindra Singh Maharaja of Patiala, a keen amateur botanist with an interest in the flora of the Shimla Hills. Singh’s student, PN Sharma from Rajasthan continued his legacy. Even today, the most skilled painters of the art are from Rajasthan including Damodar Lal Gurjar, Mahaveer Swami, Jaggu Prasad. This book is valuable for highlighting the contribution of relatively unknown Indian artists who documented the cultural and economic importance of plants.