Feminist Fire

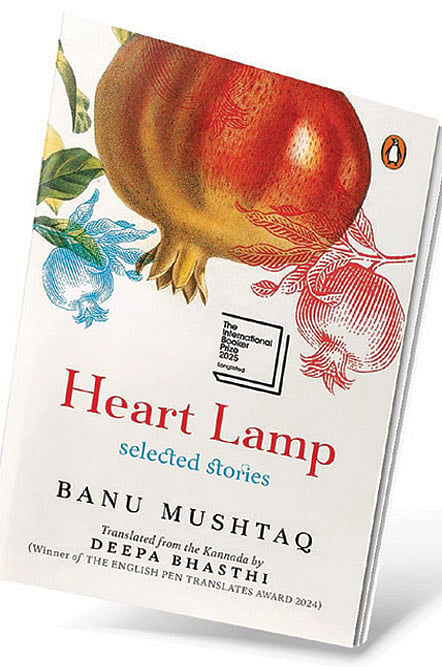

ON APRIL 8 it was announced that Heart Lamp had been shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2025. Written by Banu Mushtaq and translated from Kanada by Deepa Bhasthi it is a book well deserving of this recognition. Heart Lamp is the only collection of short stories on the shortlist, which includes five novels, and this is the first time a Kannada book has received this acclaim.

The 12 short stories in the collection centre on Muslim women and their families. But to pigeonhole these stories to a particular religion or community is to do them a disservice. Mushtaq—activist, lawyer, the author of six short story collections, a novel, an essay collection and a poetry collection—is an author and not a polemicist. She is too skilled a writer and too erudite a thinker to wield her stories as tools of either ideology or propaganda. Nearly all her stories have memorable characters, most of them end with a delightful twist. And they evoke a wide range of responses from a reader—a smile, a smirk, a shudder, a snigger, even a sniffle. To read her stories is to be immersed in the spats of mothers-in-law and daughters-in-laws, the tiffs of husbands and wives, the crusades between mothers and children. Her characters are feisty and foppish, fools and heroes, doers and dreamers, and over and above it all they are authentic.

In the translator’s note (fittingly titled ‘Against Italics’), Bhasthi (winner of an English PEN Award) writes that Mushtaq’s entire career can be summed up in the one Kannada word—bandaya, meaning “dissent, rebellion, protest, resistance to authority, revolution and its adjacent ideas.” One of the few women of the Bandaya Sahitya movement, Mushtaq’s writing is inherently feminist, and anti-class and caste. ‘Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal,’ the opening story, a perfect blend of the comic and the tragic, shines a light on a husband-wife and mother-daughter relationship. One of the few first-person stories, it is told in the voice of Zeenat the newly wed wife of Mujahid. She astutely observes her husband’s colleague’s family— Iftikhar, Shaista Bhabhi and their six children, who she describes as “all monkeys without tails” (except for the eldest daughter). It is a story that illustrates how instead of making a Taj Mahal for a wife, a husband often gives her only a stone slab. It highlights the hollow proclamations of love, and the emptiness of lovelorn words. Its last sentence, “Shaista was probably whispering, ‘She is not my daughter, she is my mother…’” highlights a key theme of the collection—women standing up for women.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The titular story, ‘Heart Lamp’ vividly portrays a woman’s struggles within the family; a young mother of five children returns to her own home as her husband has eloped with a nurse. Instead of finding support and sympathy, Mehrun’s own family packs her back to her in-laws, declaring that it is more ‘honourable’ to set oneself alight than to leave one’s husband’s house. Humiliated by her husband, abandoned by her family, cheated of her dreams, Mehrun has little reason to continue living. ‘Heart Lamp’ sears because it fleshes out the isolation of a woman, and the oppressions of society. It pits the woman against the world and shows how her only succour might lie in her own daughter. Together they are stronger, together they can take on the most unjust world.

‘Black Cobras’ is another story that highlights a mother’s instinct to protect her child at any cost. Here, a booky woman tries to inform her domestic help, whose husband has abandoned her after the birth of their third daughter, about her rights. Aashraf cares little about getting her husband back, but she needs to find a way to feed her children, and so she writes petitions to the mutawalli. The story takes a tragic and evil turn, but once again it is the women who stand up for each other.

Through fiction, Mushtaq writes about granting women property rights, the place of women in Islam, and the social and political power of the mutawalli. To quibble, however, on a second read, these stories can, at times, feel like they are succumbing to stereotypes. Too many families have multiple children, too many husbands seem blundering at best, savage at worst.

But even while dealing with issues like the violence of patriarchy, the diktats of religion and the burdens of poverty, Mushtaq’s stories are not oppressive. That perhaps has much to do with her lightness of touch and Bhasthi’s translations. Too many translations in India read like transliterations, with a few exceptions. Bhasthi makes the language her own while retaining the original nuance whether it is using phrases like “Che” or “parvardigaar” or “shaitan” or “dip-dipping”. Fittingly, the second paragraph of the opening story, ‘Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal’ spells out the nuances of words and their connotations—a pivotal conundrum for all translations. Zeenat wonders how to address her husband. Is he her “home person”? Is he her owner, a “yajamana,” or her “pati”? The opening page announces that this translation is not going to spoon-feed readers of English. It is not going to italicise non-English words, as if to pronounce the arrival of an intruder from afar. This is a wonderfully assured translation that is both confident and playful. One gets the sense that the translator is having fun with words and sentences, by bringing in robust Kannada words and not anaemic English substitutes.

Heart Lamp must also be commended for its memorable plot twists, whether it is conjecture over a burial, or an Arabic teacher with an unholy love for gobi manchurian, or how copious quantities of Pepsi introduce unlikely peace to a household. By bringing together the folkloric and the contemporary these stories are truly timeless.

The International Booker Prize which celebrates the best long-form fiction translated into English, this year received a record 154 entries. It is also the first time that nine of the 12 nominees are women. Six of these authors are featuring for the first time.

HeartLamp’s appearance on the shortlist comes after the 2022 win for Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell, and the 2023 longlisting of Pyre by Perumal Murugan, translated from Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan. At a time when the Indian English novel seems to have one foot stuck in a rut, the standout translated fiction is making its presence felt with its sparky language, original stories and fiery voices.