Dream Verse

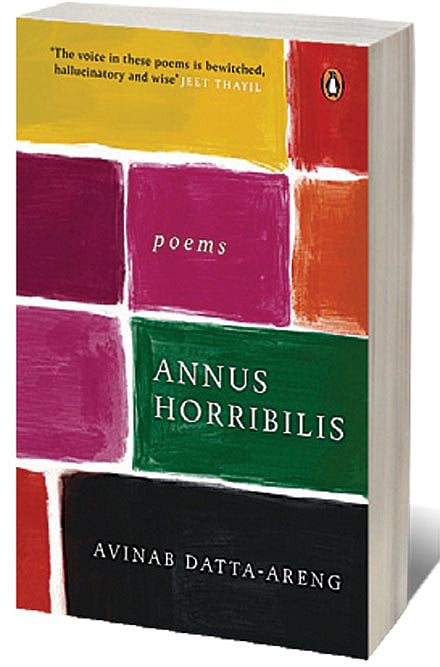

ABOUT TWO-THIRDS into Annus Horribilis, Avinab Datta-Areng’s debut poetry collection (Vintage; 88 pages; ₹ 250), there’s a poem called ‘Mise en Scène’ that fires this stunning opening salvo: “By the time they had passed / the pile of burning bodies / at the station / their arguments had become / irreversibly benign. / Which is to say / they could no longer end or arouse them.” There are two portraits of suffering in these lines: a public one, wherein there’s a pile of burning bodies near a railway or bus station (evoking Partition-era violence, perhaps, or a similarly large-scale tragedy) and a private one, which is the impending demise of a couple’s relationship; the beginning of the end. The poem only grows stronger and weirder from this point on, before ending with the line “(…) Please don’t leave me / This is changing the world”.

The irony of the narrator saying this couldn’t be more bittersweet, since it is in fact the exact opposite of what is going on—this couple has grown apart because the world is changing. Because sometimes, larger geopolitical events can have smaller, much more intimate consequences, a reverse butterfly effect if you will. Annus Horribilis is full of alchemic moments like this one that do not follow strict narrative logic (we do not know, for example, the immediate source of conflict at the heart of the poem) but the poems are irresistible all the same.

At a time when publishers typically turn away debut poets, Annus Horribilis is an exception as it showcases the solo work of Datta-Areng, who has been the recipient of the Charles Pick fellowship for fiction from the University of East Anglia and the Vijay Nambisan Fellowship for poetry.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

During a telephonic interview with the 33-year-old Datta-Areng (who lives in Goa), the poet speaks about the process behind some of these poems. “Most of the poems in this collection were written close to a decade ago,” he says. “‘Mise en Scène’, like some of the others here, is basically a ransliteration, you could say, from my dreams. I just noted them down, no matter how baffling they sounded initially.” But isn’t ‘dream logic’ notorious for stitching together possibly unrelated strands from whatever you were thinking of before your REM cycle began? As it turns out, this can be a real narrative strength, as Datta-Areng explains during our conversation. “Perhaps it’s because of my personal history or my family history, but I’ve always felt really immersed in the larger histories of the world. It’s a kind of insecurity, you could say. There are these moments when I try and make those things coalesce, where I can’t view myself in isolation, where I am inevitably connected to the world.”

While Datta-Areng was at Bombay University, he and three other students (Divya Nadkarni, Ishita Bal and Rohan Chhetri) formed the literary journal Nether. With a little help from poets like Ranjit Hoskote, and pooling their own resources, the first issue, for example, featured a photograph by Datta-Areng’s sister Jennifer on the cover. And although Chhetri and Bal later left, Nether is still spoken of fondly in poetry circles, due to its high-quality output and meaningful conversations around craft. During the first wave of the pandemic in 2020, Nadkarni and Datta-Areng revived the journal, albeit in a digital-only format. “To an extent, running a literary journal is a young person’s game,” recalls Datta-Areng. “When we started Nether we weren’t thinking about the costs or the risks. But the rewarding part is, obviously, that you get to publish the kind of work you wished you saw more of in the mainstream—and the conversations you can have with fellow writers, free from the pressures of the bottom line.”

He also contrasted the preponderance of literary journals in American academia, for example, with the analogous, much smaller space for literary journals in India. “In America, every university that has a creative writing programme also has a journal of their own,” he says. “And those MFA programmes and these journals kind of prepare you for the

specifics of a writer’s life—getting professional feedback, the economic realities of publishing and so on. I think while this may not be to everybody’s liking, it does benefit a lot of people.”

During one of the conversations published last year in Nether (titled, ‘Have we cancelled our parents?’) , Datta-Areng discussed his work-in-progress, a novel where the Indian protagonist begins to see the face of an authoritarian Indian prime minister superimposed upon his father’s face. Through the course of the novel, the flaws of the two men begin to converge, starting the process of “coalescing” private and public histories that Datta-Areng previously referred to during our conversation.

This fixation with ‘overcoming’ the influence of a father figure is visible across Annus Horribilis as well. In a poem called ‘Your Father’s Shirt’, the poet strings together a series of visceral images that interrogate the narrator’s fears regarding his love life, locating it within that same unthinking faith that most of us have in our parents.

“I failed to see your longing for your father / as a footnote to me. How could any love / that drew from within the same source / as your love for him, its dedication, be untrue? / I was deceived by my destiny of fathers. / In my life’s revolutions of fathers, my answer, / too, was disguised in a father, but the mind / meanders toward what it first sees. / First father, then fear, then flounder.”

There’s plenty of literary precedent for using the imagery of patricide or matricide as a kind of coming of age. The much-loved Irish writer Colm Tóibín has, in fact, written an entire book of essays on the topic — named, appropriately enough, New Ways to Kill Your Mother: Writers and Their Families (2012). “My understanding of this world and my emotional worldview, you could say, have always been plagued by my familial relationships, or lack thereof,” says Datta-Areng. “This is a very crude metaphor, but it’s almost like a Rorschach test, where everyone sees something different in the same inkblot pattern. My sense of affect has always been navigated through stuff like this, like my relationship with my father with whom I share an intense personal history. It has always found a way into my work. It’s something I have been trying to navigate.” To that extent, he calls his novel-in-progress “a failed novel”, until he finishes this process of navigation, that is.

To confront family is also, inevitably, to confront loss and untimely death and there’s plenty of that in Annus Horribilis. A poem called ‘Genealogy’ begins with a ‘seventh-son-of-a-seventh-son’ kind of moment, where the narrator sees three generations of his family staring back at him through his grandfather’s face, before the daunting business of grief (and therefore, coffins) creeps in.

“Dear grandfather, said / my grandfather / to his grandfather / as he stood staring / at the trunk / of the jackfruit tree / I had climbed yesterday / to yearn for you. / From up there the only / sign I could see / was a board that read / ‘Coffins available’. / My brother and I had made / a joke years ago, as we drove / through town looking / for a bottle on a dry day. / We didn’t buy one then but had / to buy one for him a year later. / My brother now in the coffin.”

And yet, the poems here are neither optimistic nor strictly doomsday in their outlook. In a poem called ‘To a Moth’ the narrator wonders whether the fleeting life of a moth is worth the effort of preservation. Is a swift death always kinder than a drawn-out demise? Writers as diverse as Albert Camus, Nadine Gordimer and Dave Eggers have weighed in on this question previously. What’s remarkable about Annus Horribilis is that despite the deadly serious matter at hand, ‘To a Moth’ is actually a funny poem. Note the way the deadpanned last line (“What’s a little more life anyway?”) uses its ambiguity (because this can be said before a life-saving or a life-ending intervention).

“The meanest thing I said / all week (to a moth trying / to perch on the screenlight): / I’m sick / of you but you’ll be / dead by dawn anyway. / I placed you on top of a bunch / of golden everlastings in the garden, wings / still spread out. (I didn’t know / you weren’t dead yet.) / You jumped from the bract tower, buried / in pollen. A little movement. / I put you back. What’s a little more life?”

RELAUNCHING A literary journal, releasing Annus Horribilis — it’s been an eventful couple of years for Datta-Areng. In a way, these two ventures are in direct opposition to each other; the book representing traditional, brick-and-mortar publishing and the all-new digital-only Nether representing an alternative route for writers to reach discerning readers. How does he view all of the ongoing disruption in the interconnected worlds of writing, publishing and journalism—Substack, Patreon, the new models of monetising ‘content’?

“I think the ways in which we process information have become so muddled,” says Datta-Areng. “In a way, the ‘disruption’ that you speak of has been happening across the last decade or so. But also, when you say ‘disruption’, I’m also thinking of the ‘disruption’ of the traditional relationship between reader and writer. I wouldn’t say that relationship is broken, but it’s going in all directions — it’s just so much easier to reach people now, if you really want to. I don’t even necessarily see it as a bad thing; I just see it as the next step in the evolution, in the structures we use for our reading and writing.”

Like a lot of debut works, Annus Horribilis is also, ultimately, interested in the nuts and bolts of writing itself. It does not romanticise or shun the uglier aspects of the craft. Instead, it bravely attempts to deconstruct everything intangible about the practice of writing. One of my favourite poems in the collection is called, quite simply, ‘Writing’. Early into the poem, you have the deadpanned brilliance of the line, “You have a different voice today, said the voice to the voice”. Spring-heeling off this one-liner, the poet goes further and further into the writer’s heart and mind, noting the little provocations and obfuscations steadily, almost dispassionately. And then in its last movement, the poem soars, laying bare the paradox at the heart of writing: that almost every text worth your time is trying to describe something inherently easier to understand than to describe.

“In another room I am rising from bed with no desire / any more to put anything down, and with a tree’s / wisdom of grief, whatever that means. / In what mode do I speak of / the rock lying there, now a different / bird coming to perch on it, / now the sense in me arriving that it’s time? / At its core always a spinning / where it appears you’re there but not.”

Annus Horribilis may have taken a decade in the making but it’s well worth the wait. Poetry lovers, in particular, would do well to keep track of Datta-Areng’s career, because this collection feels like the beginning of something special.