Can God Die?

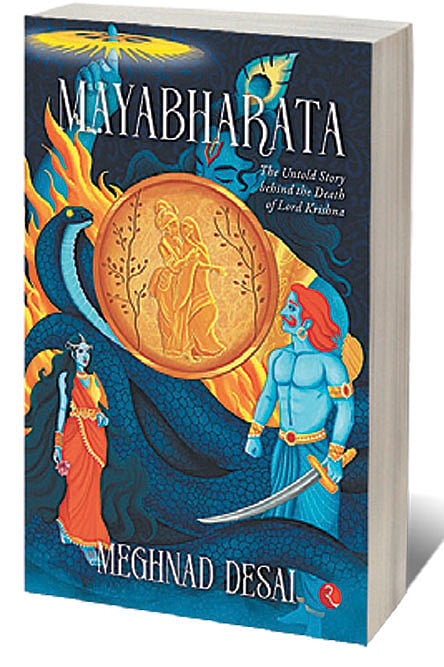

MEGHNAD DESAI’S NEW book, Mayabharata throws historical coincidence, hypothetical geographies and lively new interpretations of old stories into a cauldron bubbling with imagination, leaving the reader gasping for breath.

The setting for Desai’s story is as follows: the ghastly fratricidal war within the Kuru clan on the northern river plains of Aryavarta is over. The Pandavas have won, but it’s a pyrrhic victory, especially for Yudhishthira. Long burdened with the responsibility of being Dharmaraja, he is not only the king, he is the son of Dharma and by inclination, a man more interested in philosophical conversation about right and wrong than in devising battle formations or determining tax collections. The pressure on him to do the right thing is immense and he is in a state of profound, guilt-ridden despair.

Although Desai uses Yudhishthira to set up the plot and the narrative arc of his book, he is more interested in Krishna and what happens to him after the war. For any reader of any Mahabharata, the death of Krishna, the divine figure who controls the war and the fate of the world, comes as a huge surprise. Can god die? Can god be killed by a passing hunter who mistakes his foot for a deer? Would god exit the world of men just as it has been utterly devastated and as it enters the last and most morally compromised yuga? Who will be the dharma guide, if Krishna dies? Desai has some answers in this short book.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In his retelling of the end of the Mahabharata, Desai eschews the idea of Krishna’s divinity for the most part and plunges fearlessly into the emotional disturbances and ethical discomforts that the war has left behind. In order to sort through these, Desai calls upon characters within the traditional Mahabharata narrative, such as the Nagas (whose princess, Ulupi, was one of Arjuna’s many wives) and their king Takshaka, the mighty snake who wreaks revenge on the Kuru clan for destroying his home and family, but also deploys the profound intelligence and gentle nature of a mysterious traveller called Maya. Krishna met Maya when he and Arjuna burned down the Khandava forest and saved Maya’s life. Maya then became the architect of the spectacular new palace that Yudhishthira commissioned to establish Indraprastha as a rival capital to Hastinapura, using techniques and materials and decorative flourishes that had never been seen before among a people that built largely of mud and clay. Krishna understood that Maya had come from far away, possibly from over the vast oceans, and that he held great wisdom, different even from what Krishna himself knew, rooted in the knowledge and ways of thinking of his own people.

It turns out (and this is not a spoiler) that Maya is from the ancient civilisation in Mesoamerica which was contemporaneous with Indus Valley urbanisation in the subcontinent. The Mayans were known for their magnificent architecture, their complex systems of counting and measurement, their mapping of the stars. Maya had fled his own lands in fear of death and sought the faraway lands his father had told him about— the only other place in the world where they made huge public buildings, where they lived in cities that prospered from agriculture and trade.

Instinctively, Maya and Krishna are drawn to each other, recognising that they share the sense of a reality beyond the one they experience every day. Maya nudges Krishna towards further subtleties of dharma, and Krishna is humbled. The third man in this triumvirate of friends is Takshaka, also wise, noble and circumspect. Desai cleverly presents Takshaka’s people, the Nagas, as the earliest inhabitants of the subcontinent, the people to whom the land belongs. The Kurus are the aliens, the tall, light-haired (blonde, even) and light-eyed people who came in from the north-west, pastoralists who live by different rules, for they have neither the grand vision of city and empire nor do they listen to the secrets of the generous forest or the whisper of the fertile land. After the Vrishnis have succumbed to their own drunken genocide, Takshaka and Maya become the last chapter in Krishna’s life, abetting the processes that will fulfil Gandhari’s curse and end his time on earth.

Clearly, Desai’s imagination has made a meal out of established historical theories, our common knowledge of the past and even the ancient stories we tell about ourselves. And a rather sumptuous meal at that. No matter. This is, I believe, a book of fiction so Desai is free to construct a narrative of his choice. What becomes interesting is the historical and literary ‘evidence’ that Desai claims as his sources and resources in his Introduction for creating a “historical fiction,” as it were. Here’s an example of how Desai creates his character, Maya. In traditional Mahabharata stories, the Maya who builds Yudhishthira’s palace in Indraprastha is Maya the asura, known for his architectural skills. He was a friend of Takshaka’s and surrendered to Krishna when the Khandava was burnt. Krishna then asked him to make a palace for Yudhishthira, unlike anything ever seen before. Desai stays with the important narrative details (architecture, friend of Takshaka) but turns Maya from a local person (either an asura or a tribal king) into a traveller from a real and contemporaneous civilisation. Could such a person have made his way to the subcontinent over land and sea, following only the stars? Might Maya, on the American continent in 2500 BCE, have heard about the public buildings of the Indus Valley through traders and travellers? That determination is up to you, dear reader.

The moral crisis that the end of the war creates and the regeneration of society now required is complicated further, according to Desai, by the fact that as the king, it is Yudhishthira’s duty to impregnate all the virgins in his kingdom, “if they had no other way to simulate the onset of womanhood.” This injunction does not appear in the Sanskrit Mahabharata nor, as far as I know, in any mainstream treatise about the duties of a king. Sadly, Desai does not name the “one volume account of the story of the Mahabharata by another author” that is the basis of his new construction. Of course, the Mahabharata is capacious, it claims to hold everything within itself. It could be that some retelling by some writer in some age in some accessible language or translation or tradition added this salty little detail to Yudhishthira’s raja dharma. Again, dear reader, you decide: could that have happened?

Decades ago, Dharamvir Bharati wrote Andha Yug, a majestic play that deals with this same moment in the Mahabharata, the horrifying aftermath of the 18-day war and the death of Krishna. Bharati stays well within the parameters of the original text and produces a searing elegy for humanity. Desai’s Mayabharata lacks that power and existential bleakness, but it does prove that the Mahabharata is irresistible: for the questions that it makes us ask and for the answers that we want to give back to the story itself.