Always the Outsider

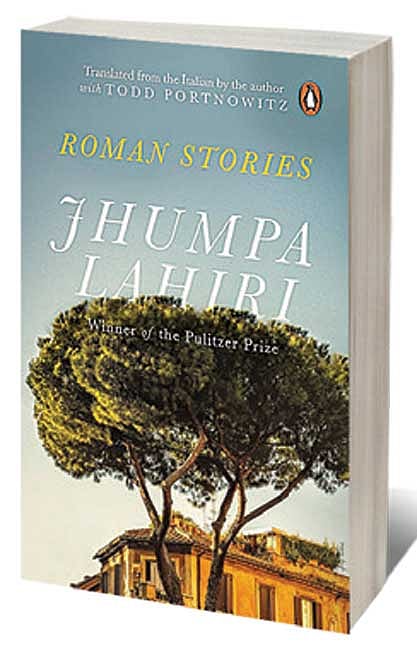

THE LAST LINE of Jhumpa Lahiri’s new collection of short stories Roman Stories reads; “This city is shit…but so damn beautiful.” This sentence approximately captures the sentiment of the collection, which deals with ideas of comfort and discomfort, belonging and foreignness. A city (in this case Rome) can make one feel both at home and ill at ease, it can be both cruel and kind, both welcoming and unforgiving.

Roman Stories can be seen in continuation with Lahiri’s 2021 novel Whereabouts, and her autobiographical meditation In Other Words (2015), on choosing to write in Italian and not English. By adopting Italian over English, Lahiri, as a writer, takes the most extreme step to show that home is never a permanent address. Roman Stories shares the same disquiet of the protagonist of Whereabouts who asserts, “I’ve never stayed still. I’ve always been moving, that’s all I’ve ever been doing. Always either to get somewhere or to come back.”

This alienation haunts many of the nameless characters of Roman Stories as they are also always in flux. ‘Well-Lit House’ brings this out vividly as in the first-person voice of a husband, it tells of a family who move into a well-lit house for the first time and realise how it can change one’s life. We recognise the cultural identity of the family only from the description of their dress, and we learn of their past when the husband says they’ve fled from a war-torn region and have lived in a camp, and a trailer. In this house the wife who wears a dress to her feet and her head draped in a veil, the five children, and her husband feel at ease for the first time, it is a “place without incident,” where the sunlight pours in. But the lightness slowly turns sinister. Residents of the apartment block begin to talk among themselves and start passing slurs. The comments turn into an embargo as they prevent the family of seven from entering and yell, ‘Pack your bags’. Unable to cope with the tension, the wife and children fly back to their home country. “At least there, despite its dangers, we’d never be forced to suffer such disrespect.” A content family of seven who found refuge in a sunny apartment, within less than 20 pages, become homeless and impoverished because they are seen as ‘outsiders’, as ‘different’. In ‘Well-Lit House,’ with the lightest touch, Lahiri unspools the threads of xenophobia and Islamophobia, how easily they arise and on what flimsy grounds they stand, and the personal toll they take.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

‘The Boundary’, ‘The Delivery’, and ‘Notes’ similarly tell of people who have moved cities or countries searching for refuge. Sometimes they find it, and at times even when they do, a stray hurtful comment like, “Go wash those dirty legs” (in ‘The Delivery’) or “You’re dirty” (in ‘The Notes’) can send the recipient hurtling into despair. All these stories illustrate how random acts of cruelty can cause a hundred cuts of disrespect and humiliation. Just as a warm and welcoming smile can make someone feel at home. ‘Notes’ is another gem of a story about a widow seamstress whose husband worked in a kitchen. She and her husband are punctilious about hygiene and keep their personal and professional spaces impeccable. She takes up a short-term job at an elementary school to mind the children. The job is easy enough. But she starts to find hurtful notes in her raincoat jacket. The third note, “You’re dirty”, makes her feel truly awful as she thinks of her immaculate home.

While Lahiri’s previous collection of short stories Interpreter of Maladies (1999) also dealt with ideas of home and away, Roman Stories does the same, but through abstraction. Interpreter of Maladies was thick with description of place and person. Roman Stories is devoid of names and identities. By freeing her writing of the concrete world, Lahiri does something new and bold, she tells us of universal rather than factual truths. By never using words like ‘refugee’, even while writing of them, she reminds us that we are all migrants.