All Over the Map

A rich and capacious second novel spreads across Ireland, India and America, but turns into a fable when it doesn't quite come together

Much of second-time novelist Kalyan Ray's cross-continental saga is set in the mid-nineteenth century period of Irish history; the Irish experience, including above all the horror of the Potato Famine, mirroring India's own as a British colony. No Country begins, though, nearly 150 years later in upstate New York where an ageing Indian couple has been murdered in their bed, the blood lurid on the sheets. Almost immediately, Ray transplants the reader from New York in 1989 to bucolic Ireland in 1843. In the village of Mullaghmore, we are introduced by narrator Brendan McCarthaigh to tax collectors burning down his friend's stone and hatch cottage: 'his da stood grinding his teeth, his ma on the ground as if lamed, and Fintan with great round eyes crying and forgotten… The fire was the colour of dark rose and madder, climbing rose and gorse— all our Irish colours. And then—for it was our Ireland and our times—everything turned to ashes.' Brendan is watching with his 'best mate' Padraig Aherne, the two boys learning early about British justice and the power wielded by distant, aristocratic landlords over their poor tenants. For the reader, the passage quoted above is an early lesson in Ray's florid, heavy-handed 'Irish' style.

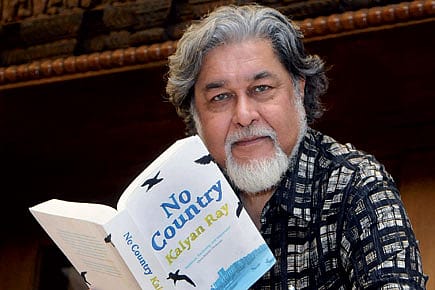

In the 1970s, long before Kalyan Ray had written a novel, before perhaps he even nurtured any ambition to write a novel, he knew he wanted to see the world. Born in Calcutta, "after 1947 to a family mourning their dispossession", he says on the phone from New Jersey, where he spends a substantial part of the year as a professor of English Literature, there was little money to indulge such frippery; their stately house was lost to them, on the wrong side of a crude, arbitrarily scratched new border. "I knew," Ray says, "that scholarships were escape routes." Teaching at St Stephen's College in Delhi on the strength of a Master's degree, he published some articles on Dickens, attracting the attention of a professor in Rochester in upstate New York who took Ray on as a PhD student. The world had opened a door.

2026 New Year Issue

Essays by Shashi Tharoor, Sumana Roy, Ram Madhav, Swapan Dasgupta, Carlo Pizzati, Manjari Chaturvedi, TCA Raghavan, Vinita Dawra Nangia, Rami Niranjan Desai, Shylashri Shankar, Roderick Matthews, Suvir Saran

"I travelled whenever I could," he remembers. "I would go to a bus station in, say, Rome, and ask 'When is the next bus?' They would say 'To where?' But I didn't care, I just wanted to get on a bus to anywhere. That's how I ended up on one going to Bari and then worked my way up the Amalfi coast." On a trip to Ireland, having run out of funds, he walked for days from County Sligo to Dublin. It's a journey Padraig Aherne, one of his key characters, replicates: walking the 100 miles to Dublin to join the great Irish 'Emancipator' Daniel O'Connell in his agitation against the British in Clontarf, north of the city. The British shut the demonstration down, shipping in thousands of troops, forcing O'Connell—who, like Gandhi, prided his movement on its non-violence—to call his rally off for fear of mass slaughter.

Bookish Brendan grows up to live a quiet life assisting Mr O'Flaherty, the village schoolmaster, reciting multiplication tables and telling stories of Irish heroes. These mythical heroes, poet-warriors like Oisin and contemporary freedom fighters like Daniel O'Connell, have an entirely different effect on Padraig; where Brendan is content to imagine wondrous men and wondrous places, preferring the idea to the reality, Padraig is driven to join the Irish freedom struggle, to march to Clontarf. As Padraig says when he takes over the narrative: 'Brendan loved stories for their own sake, savouring the sweet and sad pith of our Irish tales— but I longed for the sweat and gore of the strife itself. All our Irish songs moved my blood about, and I was so stirred.' All Padraig's feeling for Ireland, for national identity, should culminate in Clontarf but O'Connell's demonstration is stillborn, the Irish voice strangled before any expression is possible, and Padraig finds himself drinking balefully in a Dublin pub instead. The result of those whiskeys is fatal violence, the assumption of another man's identity and a hurried passage to Calcutta with the East India Company.

Meanwhile, in Mullaghmore, Padraig's childhood sweetheart Brigid—forcibly taken away by her father, in part precipitating Padraig's journey to Dublin—returns bearing his baby. She dies in childbirth and the baby is brought up by Maire, Padraig's flame- haired mother, and breastfed by Odd Madgy Finn, a Faulknerian grotesque and the half-wit orphan of a local drunk, whose own baby, the result of rape, was pecked to death by birds while she begged for food and drink. Maire dies during the Famine and Padraig's baby, Maeve, is entrusted to Brendan and Mr O'Flaherty, who become part of the desperate Irish exodus to the New World, boarding a ship headed for Canada. Rescued after a shipwreck, Brendan and Maeve (minus Mr O'Flaherty, who dies before the rescue) eventually make it to Canada and then, with the aid of a prize pig (don't ask), to a farm in Lake Champlain, Vermont.

It is among Padraig's descendants—those of his lost daughter in Vermont, his Anglo-Indian family in Calcutta, and the Mitras of Barisal, with whom he becomes involved—that the novel plays out, its dénouement at once bloody and optimistic. It is, as the partial summary above should indicate, a digressive, winding saga. Ray is prone to melodrama and sentiment; No Country is a nineteenth century novel with a huge, throbbing heart. An all-encompassing one, marshalling history, mythology and the headwinds of fate to buffet its characters from one tragic circumstance to another, its characters are not so much fully realised people as symbols, representations of the author's ideas about identity, for instance, or destiny. The machinery of the plot is deliberate, all the ludicrous coincidences necessary; because, for all the prodigious research that has gone into the novel, all the use of historical fact and incident, No Country is not realism, is not a literary simulacrum of reality, as much as it is an illustrative fable.

The reader must buy into the world of the story, must willingly accept the grinding machinations of the plot, the overdetermination, the reliance on ludicrous coincidence; even the most tenuous connection must appear predestined. However, Ray is skilful enough with his beautiful imagery and philosophical reflections (on identity, human connection, choice and family) to compensate for some of the clumsy shoehorning of history—particularly Jallianwala Bagh—into the novel.

Ray and I spoke on the phone and emailed, and he sent me detailed responses to questions I had not asked. It illuminated his thought process: the snatches of poetry— William Blake's 'A Poison Tree' and, of course, WB Yeats' 'Sailing to Byzantium'—which give Ray's novel its title and epigraphs for each section and the historical immersion necessary (Ray spent six months reading nineteenthcentury Irish history and documents) to "earn the novel's Irish voices", those of "ordinary people caught up in grand arcs of history". He wrote to say, 'Our common histories are those of travel and hybridity.' We are indeed peripatetic, migratory creatures carrying our histories and our 'homes' with us wherever we go. The results can be tragic, love lost and abandoned, but can also result in love found and perpetuated, his book implies.

Italy-based English novelist, translator and critic Tim Parks has a series of articles questioning the new internationalism of the novel, a kind of ersatz cosmopolitanism that does away with local complexity and the particular intricacies of local language. In No Country, Ray makes the argument that our stories are remarkably similar, that we all have access to and the rights to each others' stories. "The only stories worth telling," he says, "are global."

No Country is a migrant's story and America is its natural harbour; Ray is confident and ambitious enough to claim every diaspora—whether Italian, Irish, Jewish, Indian or some hybrid of all those—as his own, to adopt each of their voices. What do you do when you lose your country, lose your language, Ray asks of his characters; of Padraig, of Brendan, of Maeve. Some respond with fear, finding some small patch to call their own and sticking fast. Others adopt new countries, new languages, form new alliances. Some pick a side; the Anglo-Indians in Ray's novel, who pine for an England that is wholly constructed in their own imaginations. Others refuse to choose. More alarming than losing your country, the novel suggests, is losing love, losing empathy: that is the soil in which to root ourselves, rather than some arbitrary landmass.

If, in the end, Ray's story does not quite cohere as a novel, its many-splendoured parts, its noble ambitions, are worth your perseverance.

(Shougat Dasgupta is a freelance journalist based in Delhi)