A Patriot’s Pledge

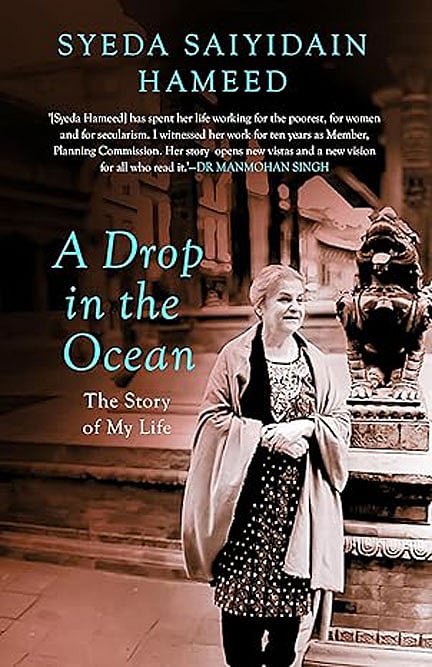

Renowned social activist Syeda Saiyidain Hameed’s memoir A Drop in the Ocean begins on a bold note, with provocative but well-substantiated contemplations about personal identity and national identity. The daughter of a pre-Partition nationalist who did not believe in borders made along religious affiliations, Hameed was raised to love her country even when it did not seem to love her in return. Love it she did—fiercely. In her senior years, however, that love has felt challenged, and this book is her reckoning with that.

Hameed describes herself as one who has “travelled the length and breadth of this country proud and free with a single identity, Indian, a person whose spirit is embedded in every stone, leaf, and blade of grass of my dharti (soil)”. Then, she recounts the unsettling incident in 2022 when she visited a friend she had known for almost all her life, from the sixth standard onwards, and saw how “decades of communal baggage gently tumbled out”. It comes in the form of a passing comment assuming that she must have a link to Pakistan, followed up by a facetious statement about having friends in Muslim bastis. It is a very mild incident, as compared to the experiences of many minorities in India, and Hameed knows it too—but it hurts her, perhaps more because it calls her national loyalty into question, than through the religious discrimination on display. It embitters her in the right way—the way of the storyteller.

It seems that this incident makes decades of her own pain, suppressed by the pride of not just being any Indian but a person of repute in the political and social work milieu, also “gently tumble out”. She recounts being a child watching post-Partition Indian Muslims pick up the pieces, and shares her own experiences as an adult: significantly, after the demolition of Babri Masjid in 1992, the Gujarat riots of 2002 and the anti-CAA/NRC protests of 2020. Her work at places like the National Commission for Women and the Planning Commission, and the direct encounters she thus had with people across the spectrum of privilege and across denominations, augment her recollections of her own life trajectory. The book also contains excerpts of poetry in multiple languages, and Hameed takes a very clear political stance when she refers to hosting Faiz Ahmed Faiz while she lived in Canada, and goes on to say, “So Faiz’s toast is raised… to Gauri Lankesh, Gobind Pansare, Kalburgi, Dabholkar, and… yes to Sudha Bhardwaj, Gautam Navlakha, Varavara Rao, Father Stan. Hum dekhenge!”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

As with many disillusioned people, admitting the present is one thing but letting go of nostalgia is another. Throughout the book, Hameed vacillates between pride and horror, both sprung out of love for India. The pain begins early, but always buffered by the myriad advantages of a charmed life. Throughout this memoir, it is evident that the highly accomplished Hameed, who would eventually be conferred a Padma Shri, had always been largely protected from the experiences and tribulations of most Indians—she observed these in public service, consultancy, activist and reportage capacities, but at a certain remove.

At points, this memoir frustrates because it is the record of a very sheltered, very privileged life—one in which everything from family connections to foreign citizenship have allowed patriotism to dominate sentimentally, even when events contradict that sentiment, and even when Hameed’s own work itself had long before been revealing of on-ground realities. On the other hand, A Drop in the Ocean works because it serves a sort of barometric evidence: of how the hatred Hameed describes and the fear she feels have touched even the echelons that she occupies, which indicates a far greater, perhaps irreversible, spread of the same.