A Home in Memory

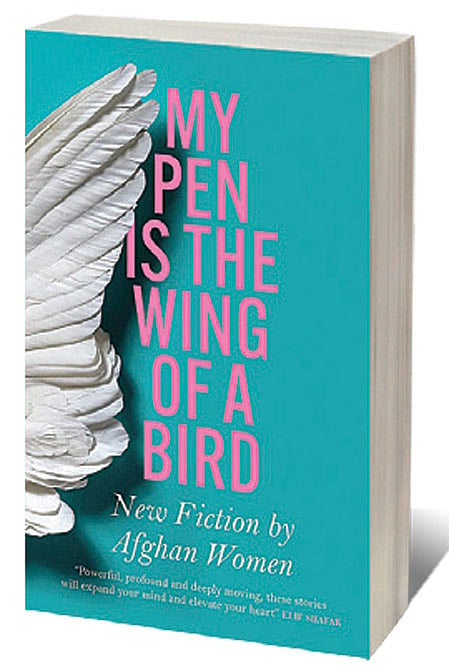

THE TERM SIAH SAR appears several times in My Pen is the Wing of a Bird: New Fiction by Afghan Women. It’s a term used to describe women, often in such a matter-of-fact way that the average reader may not realise the implications of it. As Anahita Gharib Nawaz, in her story ‘D for Daud’ (translated from the Dari by Zubair Popalzai) explains, “… When I see her, I understand why women are called siah sar. She represents the true sense of the word: one who is destined for darkness.”

An unsettling reflection on the status of Afghan women, indeed—a status that is reinforced with every single story that forms this collection. There are illiterate women here, and educated women who must soldier on, working even as violence explodes all around them. There are women struggling against poverty, corruption and the ruthlessly patriarchal mindset of a society that piles on responsibilities and strictures to confine women, without according them any space for their own dreams, their own ambitions.

And yet, there are women in these pages who are not cowed. There are the more obvious examples: the eponymous Ajah of Fatema Khavari’s story, who shows the way to a village threatened by floods; or Sanga, doggedly going on reading the news even as bombs fall all around the building where she works, in Sharifa Pasun’s ‘The Late Shift’. But there are others, too, who show determination and strength in their own way: Rana Zurmaty’s Haska, for instance, in ‘Haska’s Decision’, who finds an innovative solution to the bullying she faces after being widowed. Or the memorable unnamed protagonist of Marie Bamyani’s ‘The Black Crow of Winter’, hardly the stuff stereotypical heroines are made of, but a heroine in her own right, coping with dire poverty in the only way she knows.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Grinding poverty is one of the recurring themes of this collection; the other most notable one is violence. The war that has gripped Afghanistan, in different forms and guises for the past several decades, comes through sharply and painfully here. Suicide bombers, gun shots, flying shrapnel, and the long-term, wide-ranging devastation caused by never-ending violence: the number of stories about people living their lives against this backdrop is heart-breaking. In ‘Sandals; in Khurshid Khanum, Rise and Shine’; in ‘What Are Friends For?’ and several other stories, there is a veneer of normality—as non-Afghans might know it. Children play and go to school, men and women go to work, there is laughter and love. But violence is never far, and the way it engulfs the narrative when least expected makes it that much more impactful.

But there are stories, too, that show another side of life in Afghanistan. There is, for instance, a young girl’s obsession with a beautiful pair of red boots. An Afghan immigrant, now in the US, whose ache for her homeland comes through in the subtlest and most personal of ways. A boy, struggling with a dawning sense of his sexual identity.

In the afterword to the book, Lucy Hannah describes the way this collection was built up. The very real obstacles—writer’s block is nothing compared to this—that the 18 women whose stories comprise this book had to surmount. From unreliable connectivity to frequent power outages, to the sheer danger of speaking up in a Taliban-ruled country, these writers fought daunting odds just to be able to have their say.

And what a say it is. Each of the stories offers an insight not just into Afghanistan, but what it means to be human. There is emotion here, sensitivity, empathy and wisdom. Pain, fear, grief. Hope, strength. In its own way, at its own level, inspiration.

One of the finest collections of short stories in a while, this one is a treasure.