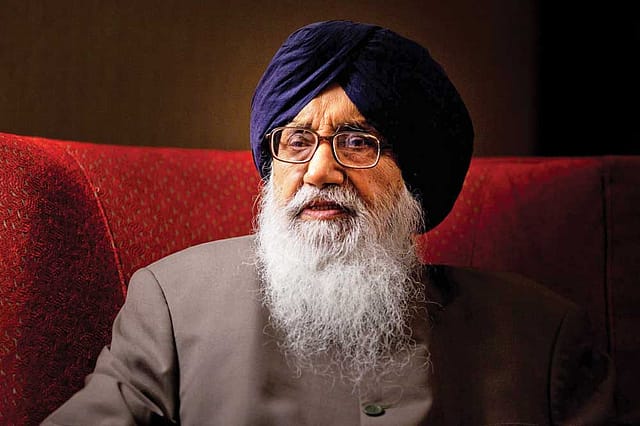

Parkash Singh Badal (1927-2023): The Man Who Normalised Punjab

THE YEAR WAS 2002. A young civil servant was seconded to the office of Punjab's Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal. As can be expected, proximity to power was relished by the bureaucrat. But within a year, the ambitious man sought a transfer out of the chief minister's office. The reason was not official displeasure or misdemeanour but plain exhaustion. The chief minister's daily life was gruelling. On many days in a month, Badal Sr would wake up very early, perform his ablutions, pray and after an early meeting with his officers, leave for different parts of the state to meet people. By the time he would return to Chandigarh, it would be late evening. The same schedule was repeated, perhaps too often for the members of his office. At that time, the chief minister was in his 75th year and could put a person younger by many decades to shame with his sheer stamina for work.

That scorching pace of work and monitoring were essential to keep a tab on Punjab, a state with a history of restiveness and insurgency. Badal Sr, a five-time chief minister, had witnessed everything: Independence, development, the vicious politics of the 1960s, insurgency, peace and decay. He was almost synonymous with Punjab.

His political achievement can be summed up in a single line: he brought political stability to his state. This was no small feat. From its birth in 1966—when the demand for a "Punjabi suba" or Punjabi province was conceded—the state remained a turbulent entity right until the end of the 20th century. Badal Sr was witness to the tumult. During this time, Punjab was the cockpit of political intrigue. A degree of stability was established by the mid-1970s, but one that proved to be shortlived. From 1979 until the mid-1990s, terrorism distorted its politics beyond recognition. These events had a national spillover to the point that the Constitution's emergency provisions (Article 356) had to be amended in quick succession in 1990 and 1991, solely because order could not be restored in the state.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

All this came to an end in 1997 when Badal became chief minister for the third time. Atal Bihari Vajpayee was at the helm of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) then, the successor to the Jana Sangh that had once been a partner of the Akali Dal in Punjab. The fit was natural: Badal would get a free run in Punjab while Vajpayee would provide him support from New Delhi. The arrangement worked very well: Badal 'normalised' Punjab and Vajpayee provided economic support to a state battered by terrorism. When Badal exited office in 2002, his was the first ministry to have completed its five-year term in two decades. By then the turmoil of the last 40-odd years was a mere memory.

The secret behind Badal's success was his ending of internecine conflict within Akali politics. Akali politics rested on two planks: religious mobilisation through its ecclesiastical wing— the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC)—that controlled gurdwaras and mobilised the faithful; and through the party proper, the Akali Dal (later Shiromani Akali Dal or SAD), that handled other issues, such as interests of farmers. But whenever the party would come to power, the SGPC would try to assert its dominance over the political wing, SAD. This was an in-built destabilising feature of Akali politics. At one time, powerful SGPC overlords like Gurcharan Singh Tohra, the 'fox' of Punjab politics, and Jathedar Jagdev Singh Talwandi would routinely fish in troubled waters. In 1999, Badal defanged Tohra who formed his own Akali faction. To no avail: there were no takers for his brand of religious politics and he died a bitter man. After that, there was no room for meddling by extra-constitutional authorities in Punjab's governance.

Paradoxically, all this came at a price. By 2000, most of Badal's rivals had been swept away. Those who remained within SAD's fold bought peace with the man from Muktsar. Soon enough, SAD caught up with political trends that prevailed in regional parties across India: a single family dominating an entire political party until the two were indistinguishable. By that time, the elder Badal began grooming his son, Sukhbir, for a bigger role. BJP—the long-term partner of SAD—acquiesced to Sukhbir being made Punjab's deputy chief minister in 2009. His close alliance with the Chautalas of Haryana made for a formidable bargaining bloc of farm leaders. Higher MSPs and other concessions for farmers flowed effortlessly to Punjab.

When Badal became chief minister for the first time in 1970, Punjab was one of India's fastest-growing states and among the top in terms of per capita income. By the time he demitted office for the last time in 2017, Punjab had become a laggard and routinely ranked close to last among major states. The heyday of prosperity, when Punjab was the envy of India, had come and gone. On the surface, all political parties in the state, especially SAD, blamed the phase of terrorism for Punjab's worsening economic fortunes. The reality was, however, very different. When Punjab had large sums of money at hand due to the largesse of the Centre that purchased every single grain of wheat and rice grown there, it chose not to invest that money in building infrastructure and human capital. Decades after India began liberalising its economy, Punjab continued to bank on agriculture as its economic mainstay. While southern states invested heavily in education and infrastructure, Punjab did not invest even a fraction of what it received from the Centre. The IT revolution, manufacturing and other modern sectors never touched Punjab.

This was the price of stability that Badal Sr ushered in Punjab. His political achievements were formidable: at one time, no one knew how to 'solve' Punjab. The various 'formulae'—to use a quaint expression that had currency in New Delhi during the 1980s and 1990s—were just paper planes until Badal took charge and systematically removed all elements that had the potential to create chaos. When it came to the political management of a difficult state, he stood way above the ruck of leaders in most Indian states. But the same cannot be said about his ability to steer Punjab to a better economic future.

His aura looms large over Punjab. Perhaps that was a function of his time. His rivals were wily and ruthless even as he exuded calmness. Today, Punjab's politics is dominated by minnows. It is not surprising that the state is witnessing political turbulence once again. Farmers, the constituency that Badal Sr took care to nurture and control, are on the warpath and the current political leadership of the state is clueless about what to do. Had Badal Sr been around, he would not have allowed the situation to arise in the first place. In his time, farmer unions like the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) were kept firmly in their place. The leaders of these unions—who masquerade today as 'farmers' leaders'—were no more than country bumpkins who knew their place or were reminded of it, often enough. But loosen controls over them and Punjab will become ungovernable. Badal Sr knew that and more. His political finesse will be missed in Punjab for a long time.