Imagining Saif Ali Khan as a Lizard

Three Bollywood costume designers talk about their unique techniques for visualisation, research and getting the details right

Imagining Saif Ali Khan as a Lizard

Dolly Ahluwalia Tewari, costume designer for Omkara and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, on her 'animal theory'

Just as emotion is at the core of the human experience, it is present in every frame of cinema. There are emotions even in clothes. Clothes breathe. That's why, besides the script and director's vision, one of the things I focus on while doing film costumes is the cast. I am always curious who is playing which role, their body language and how they need to carry off their costumes. How the characters speak is also important because it reveals who they are and where they belong. That's the starting point of creativity for me.

I use what I call an 'animal theory'. By this I mean I visualise the characters of a film in terms of the animals they resemble, or, in some cases, how similar they are to an object. When I read about a character, I ask myself, 'Does s/he look like a ball, pen or a tree?' All humans have animalistic instincts. In the most trying of circumstances, our internal animal takes charge of our body.

When I heard that Saif Ali Khan was playing a character in Omkara based on Iago (of Shakespeare's Othello), I could see him as a lizard. A lizard is sinister. It's always alert—waiting, watching and looking right through your eyes. You see it, and within seconds, it's elsewhere. When there is danger around, it changes colour. Iago is similarly untrustworthy. On the other hand, Desdemona (played by Kareena Kapoor) was like a jasmine flower, a bud trying to blossom. To emphasise her purity and innocence, we gave her whites in romantic scenes.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

For Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, I had the image of Farhan Akhtar as a tiger and also as a graceful white horse. A horse looks harmless, but it's a very powerful animal. Most of its strength lies in its legs. Taking a cue from the horse's anatomy, director Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra and I discussed the shape of an athlete's legs from where s/he gets grip and power. It was suggested that we focus on Farhan's arms along with his legs because though the legs bear the weight, the arms give them motivation. It's the body's way of 'give and take.'

In costume design, the director's contribution is a great deal. It's good to be on friendly terms with the director. Professional relationships can be too dry for creativity. Vishal Bhardwaj and I share that kind of relationship. He never runs an artiste down. He will never say, "Dollyji, it's not good," or "I don't like it." When we were filming Kaminey, he would come and say, "Very nice but can we put some more masala in this?"

Similarly, Shekhar Kapur gave us a free hand in Bandit Queen (based on the life of dacoit-turned-politician Phoolan Devi). He said, "I want each and every character to come out from the soil—Indian soil." That was his brief. I was in love with Shekhar. He was such a good-looking fellow. The first time we met, I said teasingly, "Shekhar, I have to give you a hug before we start." I had to keep my romantic feelings aside to work with him. And what an experience Bandit Queen turned out to be. I learnt the ABC of costume design from that film.

I didn't know anything about the lives of dacoits. I decided to do a little research of my own. A friend helped put me up with a gang of 13 dacoits and a young boy near Chambal. They were very nice to me. They assured me of protection and safety. I cooked for them. One night, we sang Bollywood songs while some members of the gang played dholak and harmonium. They sang Kasme Vaade, that famous song from Upkar. I broke into Jhumka Gira Re from Mera Saaya, and everybody joined in. The costumes of all the dacoits were real, rugged and textured. My National School of Drama and theatre experience had taught me how to age clothes.

Bandit Queen was the first film I handled on my own. I had no idea whether I had done a good or bad job. One day, cameraman Ashok Mehta was framing a wide shot from the top of a crane. When he saw me, he came down and said, "Beta, come here. Do you want to see what you have done?" I was frightened. I thought I had messed up.

He put took me up on the crane and said, "Look what a brilliant job you have done!" I asked him, "Sir, why do you feel so?"

He explained how the brown colour of the ravine stood out against the sky and how the faded green merged with the dry bushes and how the clothes blended so well with the landscape. That's how I understood the relationship between colour, texture and background. To this day, I believe God is in the details. If the background details are weak, the foreground details would appear incomplete. It's like chess. What's a king without knights and pawns?

Gatecrashing Delhi Weddings

Niharika Bhasin Khan, costume designer for Kai Po Che, Band Baaja Baaraat and The Lunchbox, on unconventional research

Clothes have the power to transform a movie. They tell a story. You learn a lot about the person from the clothes s/he wears. Characters wear clothes as much as clothes wear characters. Sometimes, we have to make that impact in just two seconds. That's how much time we might get for a scene. For The Lunchbox, the costume and look of the characters told us a little more about their private lives. Nawazuddin Siddiqui comes in first as a Saudi Arabia-returned man who doesn't put much thought into his clothes, but once he meets Irrfan Khan, he starts idolising him and everything about him changes. His confidence and way of dressing reflect those changes.

Irrfan works as a government official. So we gave him subtle colours. But when he is going on a date with Nimrat Kaur, he works a little on his appearance. Nimrat, on the other hand, rarely goes out of her house. You only see her cooking and her clothes literally smell of food. When she is trying to seduce her husband, she wears what she wore on her honeymoon, a slightly tight dress that suggests she isn't the demure newly-wed she once was. She has had a child since and has put on weight. We didn't give her dupattas because that's how most housewives are within the privacy of their homes. In fact, she may look like a bored housewife on the surface, but I know men who found her sexy in her white kurtas with black bra straps visible. If we had given her a prim and proper look, it would perhaps have backfired.

I don't ever want the clothes to jar and take attention away from the film. Usually, it's the director, art director, director of photography and costume designer who decide the look. The colour palette is determined by the director of photography. All of us work under the director's instructions. The look depends entirely on the director's vision. My design philosophy is to ensure as much. We may have ideas of our own, but even if they are damn good ideas, translating the director's vision takes all our effort.

Then come the details. Although I am not a 'details person' in my own life, I pay close attention to it in films. In Kai Po Che, the whole thing of Govind (played by Raj Kumar Yadav) wearing tight half-sleeved shirts was inspired by a conversation I overheard at a friend's place. They were talking of somebody who wears small shirts to save money. Govind is like that. He is not the sort to fuss over appearance and wouldn't mind if he had to spend less or nothing at all on clothes. Another character, Omi (Amit Sadh), is a priest's son and though he owns a sports shop which also sells shoes, he only wears chappals. Ali's green taaweez was another minor but important detail.

To research Band Baaja Baaraat, I gatecrashed weddings in Delhi. I wouldn't recommend that to anyone. However, any kind of research can be useful. Speaking strictly for myself, I rely on research because I don't have that background. For Kai Po Che, I studied the way Gujarati boys dress and behave, the mentality of middle-class Gujarat and the colours and textiles there. For Anurag Kashyap's upcoming period film Bombay Velvet, we did eight months of research before starting work. We read tonnes of books, visited libraries in Mumbai, Delhi and Kolkata, spoke to experts and even sourced photographs of the 1970s' Bombay from friends and acquaintances.

If you don't know the world you are trying to recreate, you have to research it. Your mind stores its own observations, of course. I was recently at my high school reunion and I can't tell you how many style details I picked just by observing people. "My God," I said. "I am going to use that detail for a film someday."

Getting Orgasmic Over the Script

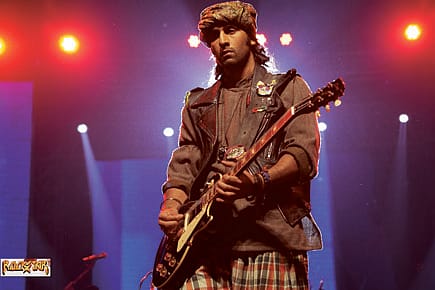

Aki Narula, stylist for Rockstar and Barfi!, on why he smeared Burnol on Ranbir Kapoor's shirts

Director Imtiaz Ali once told Tehelka magazine, "Aki doesn't design clothes. He designs people." I think he got it bang on. My clothes are honest and organic. They come from a space that lends an organic honesty to the characters and the story, particularly in Rockstar and Barfi!. The key trick in getting costumes right is to have them absolutely belong to the character. For example, you have to know where the character is coming from, what he can afford to wear, what his likes and dislikes are. It's about creating a wardrobe.

For me, the script is God. You've got to be excited about the script. Only when that perfect marriage happens can you actually peak an orgasm.

Imtiaz Ali sent me the script of Rockstar at 8 pm. I read it over the next few hours and called him up at 3 am. I was like a child bursting with ideas. The next day, I showed him a lot of pictures and references that I had worked on overnight. The starting point for Jordan (played by Ranbir Kapoor), who is like a tormented musical genius, was that he had to have a distinct identity. We had no reference points in mind, no one really who we could have emulated because that was not what Jordan's journey was about. We didn't want him to be like, say, Jim Morrison.

In India, we have no concept of a rock star. Jordan's look was created out of pure love, originality and imagination, keeping only his struggles and growth in mind. Every garment that Jordan wears has a story to tell. He starts out as a simple college-going, middle-class Delhi boy. He goes from being a student to having epiphanies at the Nizamuddin Dargah to finally superstardom, Kashmir and Prague. Every experience adds to his depth as a person. For example, the salwars he wears in Prague are influenced by what happens to him in Kashmir. And then, the experience of his Prague days is reflected in his final concert where he wears a military-inspired jacket. Even the guitar strap has charms and anecdotes that remind him of his journey—for example, it has his mother's mangalsutra boondi, the green fabric of the dargah where he started singing, the red mata-ki-chowki chunri when he used to do jagrans.

Remember the sweaters he wears in college? We got them handknitted by Delhi housewives because Jordan comes from the kind of family where grandmothers knit sweaters. We shopped at various markets in Delhi's Sarojini Nagar, Palika Bazaar and Janpath. All of Jordan's salwars were made at my workshop. T-shirts were cut up to make hoodies for kurtas. It was not one of those films where you just fly abroad, buy clothes in bulk and put them on the actors. That's not the kind of costumes I believe in.

Another fulfilling experience was Barfi!. It was an emotional journey for me. I was born and brought up in Kolkata and have stayed there for 26 years. I believe the best journeys are those that take you back home. Barfi! did that to me. Sourcing saris for Ileana D'Cruz from shops frequented by my mother in Kolkata was like revisiting old times. I went back to all the old khadi shops to get stuff for Ranbir, especially buying shirts and getting them starched in Kolkata because there's a certain starchy feel that only dhobis there deliver. A lot of work went into Ranbir's styling. We used to apply Burnol cream on the underarms of shirts to give them the effect of sweat stains. We used Brylcreem on his hair. He also carries a comb.

For Priyanka Chopra's look, we thought of school-girlish fabrics; little blouses, bloomers and skirts, all which were sourced in Kolkata.

Yet, one thing I never do is overdo. Sometimes, costumes are so overpowering for a character that they detract from the film. That should never happen. My clothes never scream for attention. They blend in—quietly.

—As told to Shaikh Ayaz