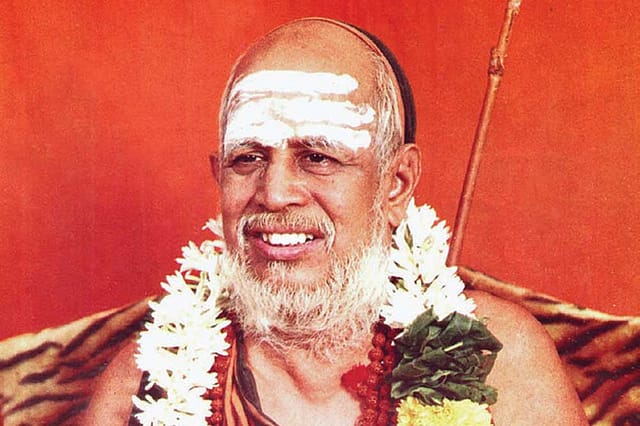

Jayendra Saraswati: The Saint Destigmatised

THE BRAHMOTSAVAM at the Kamakshi Ambal temple in Kanchipuram, renovated only last year, was underway when news of the Shankaracharya's passing fell like a bomb from the sky, crumpling a mass of devotees. With the death of the restlessly intelligent pontiff of the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, Acharya Jayendra Saraswati, at the age of 82 on February 28th, a sense of numbing dread has crept over the elite community of Tamil Iyers who believe the acharya to be an incarnation of Adi Shankara, the father of Advaita philosophy. In a couple of days, when they've said their final prayers and moved on to stand by the next Jagadguru, the 70th in a supposedly unbroken line of seers, to take over the Peetham, a boggling mix of devotees, frenemies and politicians will take stock of his life, and what it meant to them. "He was a perceptive man who always knew what to say to anyone—a naughty child, an egotistic politician, a man on the brink of a nervous breakdown," says K Chidambaranathan, a 49-year-old businessman from Vellore who last met the acharya—reverentially referred to as periyava, the elder—a month ago to seek blessings for his daughter's wedding. "I expected a cursory greeting. But he could see I was worried. He told me, 'Do not think, will my darling daughter be happy? Assume happiness and make it possible'."

Born on July 18th, 1935, in Tiruvarur district, and chosen by Kanchi 'Maha Periyava' Chandrasekharendra Saraswati, the 68th pontiff, as his successor in 1954, Jayendra Saraswati had rather large shoes to fill, but he always chose his own path. Unlike other Brahmin gurus of his time, he was accessible to the common man. His pro-Hindu politics, in direct contrast to the secularist moderation of his predecessor, was moulded in the furnace of the anti-Brahmin movement in Tamil Nadu, and spread to Delhi with his offer of mediating between the stakeholders in the Ram Mandir issue. By the late-1980s, he had already become a power centre in the parallel Hindu resurgence movement in Tamil Nadu. Then, one day in 1987, he mysteriously disappeared from the math, only to be tracked down in Talacauvery, Karnataka, three days later. His return 17 days after he was assumed to have absconded was discomfiting for the math, which had already appointed another successor, but his devotees easily forgave the errant saint. The 90s saw him emerge from the shadow of the Maha Periyava and land in the thick of political action in Tamil Nadu, with the friendly AIADMK government appointing him to state-level committees and cracking down on mass conversions, and his own efforts to reach out to Dalits, whom he saw as a people in need of spiritual direction. With the coming of BJP-led governments at the Centre in the late-1990s, his sphere of influence grew wider and wider. Until the ignominy of 2004.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

On Deepavali in 2004, when Jayendra Saraswati was arrested in the middle of the night from Mahbubnagar in Andhra Pradesh for his alleged involvement in the murder of A Sankararaman, the manager of the Varadaraja Perumal temple in Kanchipuram, the media asked DMK patriarch M Karunanidhi if he would have done the same as Chief Minister. "Had I been Chief Minister, the murder would not have happened at all." Ever the quick- thinking politician, Karunanidhi had implied that he would have successfully mediated between the math and Sankararaman to put an end to the mutual animosity. The dramatic arrest of a man millions worshipped as a living god—he and 22 others including his successor Vijayendra Saraswati were acquitted in the case in 2013—was an oversize gesture by the then Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa. The DMK had been demanding action against the Peetham, but Jayalalithaa, known to be a devotee of the math, went a step further. To silence the emerging cacophony of critiques against her government, she targeted the Shankaracharya in an effort to win back the Dravidian vote, cut the Hindutva cord, and demonstrate her power over the most powerful math in Tamil Nadu. "Her arrogance did her in," the Shankaracharya is known to have said. His own ambition proved to be his downfall, forever staining his legacy.

It is said that time makes use of men to fulfil itself. Acharya Jayendra Saraswati, then, was a man who proved useful in more ways than any pontiff of his time.