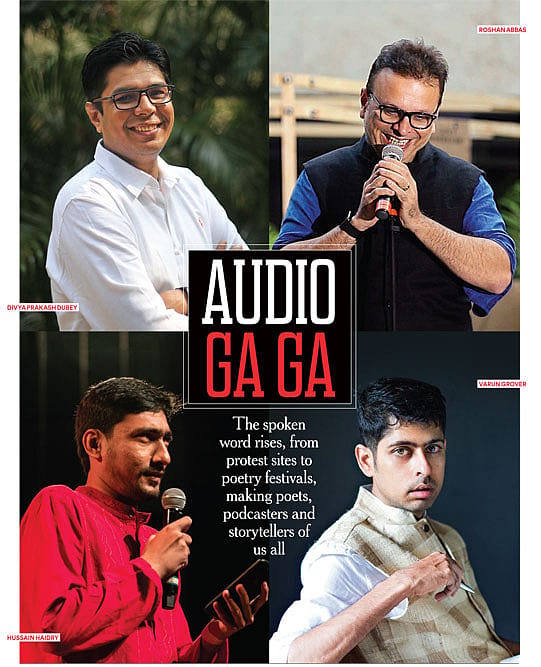

Audio Ga Ga

THE PIYA MILAN Centre of Lucknow zoo, the masala-soda of Allahabad, the late night gully cricket of Benaras. Divya Prakash Dubey's father worked in Sales Tax and the family travelled across north India. Little did little Dubey know he would be using people, places, smells and sounds from that time to tell stories that people would be riveted to.

Dubey, author of four Hindi bestsellers which have cumulatively sold a million copies, is an engineering graduate from College of Engineering in Roorkee with a management degree from Symbiosis. Just another middle-class man, whose greatest failure was perhaps that he couldn't get into IIT. But he did pretty well for himself, nonetheless, becoming Area General Manager of Idea Cellular in Mumbai. That was before he met Neelesh Misra there one day, a journalist who had quit to tell stories on radio for a living, and decided he would do the same.

The platform can vary, from live events, to Audible Suno, a new ad free storytelling app launched by Amazon, but the tales are multiplying. Dubey is one of the many stars created by the headphone revolution, which has seen the spoken word packing a punch. Across India, poets, storytellers, singers and rap artists are enjoying a revival as never before, bringing to life characters and cities, lived experiences and unlived fantasies. From countless young protestors at Jamia Millia Islamia to the students of Aligarh Muslim University, singing Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Rahat Indori with equal ferocity. From the women of Delhi's Shaheen Bagh to the citizens of Mumbai's Azad Maidan, echoing Varun Grover's Kaagaz nahin dikayenge and reciting the Preamble to the Constitution. From Hussain Haidry, son of a bookshop owner from Indore, to Misra, a Lucknow-based former journalist who lives in a house called Slow, the movement has created new stars, new events, and new organisers.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

There's Suno, an unlimited service that's the first of its kind for Audible, over a year after Amazon launched Audible India. CEO Don Katz says the service deepens the mission to honour India's "proud and distinctive storytelling culture by connecting the best writers and actors to listeners through unique, original audio-first stories created by the most gifted Indian directors, authors and actors". From Misra talking about how war impacts families in a 30-episode series, Yoddha, to Guneet Monga and Tahira Kashyap collaborating on the latter's cancer survival tale in My Ex-Breast, Suno hopes to gift "found time" to busy people, providing a rich destination for insight and inspiration.

It's a world that started taking shape around the end of the noughties with Open Mic events in and around Mumbai where poets, comics, storytellers would just come together and share their tales. Annie Zaidi and Manisha Lakhe had started Caferati around the same time. Suddenly everyone was allowed to speak about their experiences at cafes which have since closed down. Even as the visual world was taking off, the word was finding its own audience. As a young chartered accountant Haidry remembers being one of those who shared the stage with a young Varun Grover, who was yet to be part of Aisi Taisi Democracy, and Gazal Dhaliwal, who was yet to find her distinctive voice, which later led her to write movies and lyrics. Haidry went back to Indore after two years, got an MBA degree from IIM Indore, and then returned to Mumbai in 2016, for good. His Hindustani Musalman, a poem about being Muslim in today's India, went viral when it was broadcast on YouTube by the storytelling and events curation company, Kommune. Fame followed, close on the heels of work with Anurag Kashyap (he wrote lyrics for Mukkabaaz) and Karan Johar (he is co-writing his next film, Takht).

Spoken word rescued Roshan Abbas as well. The All India Radio veteran and Hindu College theatre enthusiast was exhausted after making his first film in 2011, Always Kabhi Kabhi, an experience that was vastly different from how he had imagined it. He was depressed and says his friends staged "almost an intervention" and started to meet once a week to tell each other stories. One thing led to another and Kommune was born in 2015 with his friends actor and presenter Gaurav Kapur and musician Ankur Tewari. It now stages events where actors, poets and storytellers talk about what moves them, inspires them and motivates them. The latest version of their event, Spoken Fest, has taken off and has featured an array of stars, from Kubra Sait whose performance got her cast as Kuckoo in Netflix's Sacred Games, says Abbas, to Jim Sarbh whose range, from Neerja's villain to Made in Heaven's rich boy, has made him Bollywood's current It Boy. There's also the teenage Simar Singh's UnErase poetry which has helped launch the careers of the remarkable Gaurav Tripathi whose spoken word Lord Ram in Court remains a searing indictment of contemporary India as does Aranya Johar's fierce A Brown Girl's Guide to Beauty.

Podcasts too are rising in popularity as well, whether it is long running series such as journalist Amit Varma's The Seen and the Unseen or newer efforts such as Christina MacGillivray and Aditi Mittal's Working Title, which investigates why women are dropping out of the workforce, with humour, candour and sarcasm. What is driving the return of the spoken word? Partly technology. MacGillivray believes more apps available on phones will fuel the greater intimacy afforded by audio, freeing it of the geographical restrictions of radio. "Podcast is essentially radio that no one can stop you from making, plus it doesn't have the high cost of video," she says.

The need to express ourselves and reconnect with our roots are two interconnected forces in the world today. In an environment of increasing loneliness and isolation, holding on to nostalgia is a given and with everyone becoming a publisher, there's never a dearth of stories. Add to that the time spent in traffic snarls in India's increasingly clogged cities—according to a report by The Boston Consulting Group in 2018, on average, travellers in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Kolkata spend 1.5 hours more on their daily commute than their counterparts in other Asian cities during peak traffic. And it's no accident that one of the biggest stars in Bollywood today is former RJ Ayushmann Khurrana, who has often said how much he owes to his years in FM. Two recent beloved films have also focused on lead characters who talk to lonely strangers for a living, the naughty but nice Dream Girl, starring Khurrana as a sultry Pooja, and Tumhari Sulu, which features a remarkable Vidya Balan, who radiates empathy and warmth as the throaty late night talk show RJ Sulu, who is as charming to seedy auto rickshaw drivers as she is to lonely widowers. Nothing connects better for what Abbas describes as the "loneliest generation".

The spoken word is protest as much as it is poetry, it is the azad nazm (prose poetry) as much as it is the plain story. It has also meant the rise of spoken Urdu, often by non-Muslims, a fact that Saif Mahmood, lawyer by day and storyteller at other times, remarks upon. Son of a well-known jurist and former cosmetics CEO, Mahmood grew up with poetry at the dining table but is struck by the youngsters who now write poetry in Urdu, albeit in the Devnagri script. It has allowed the most unusual things to become popular—for instance, Kallo, a story of two women in love by Pakistani author Sameena Nazeer brought to life by Old Delhi's very own storyteller Fouzia Dastango. It is enough to delight Mahmood who says Urdu cannot be killed in this country. "What's more, it is no one's monopoly," he adds.

THE SPOKEN WORD has become the uncensored social commentary on our present, seen at its most effective in the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protests. Young poet Sabika Abbas Naqvi believes it has allowed youngsters to focus on themes frowned upon by traditional poetry: mental health, gender, love, post traumatic stress disorder or even falling in love at a protest site. It has allowed the articulation of resistance, she says, in a mix of languages, English, Hindi, Urdu, as well as other regional languages. This democratisation of ideas, points out Haidry, has enabled an outsider like him to break into the insider culture of literary circles. "Even if it is spirited speech, it is communicating an innate human emotion. In an accessible way," he says. In a way, that connects grandparents to the grandchild, CEO to the driver, the South Delhi resident to her tailor. "Every day I become the other," says Misra about a platform which has allowed him to tells stories as diverse as Sa Re Ga Ma Pa, about a woman who comes to her husband's home after marriage and is denied time with her best friends, the sitar and the table, or Vidaai ke Baad where again Misra imagines the life of a new bride. "So many people have come up to me and told me it reminded them of their mother," says Misra.

And here the role of radio remains paramount. With 99 per cent of India covered by radio and the growth of FM, the RJ remains an abiding star. Like RJ Stutee of Fever 104 FM who says as a radio jock, she has realised that the need to be heard and understood without being subjected to unnecessary judgment is a universal need. "On radio, no one can see your face, you can choose to keep your identity anonymous but unlike the internet, radio empowers people to share their thoughts, keep it raw, and really open up. That someone is listening to them makes them happy. It also, at times, makes one realise how solitary we have all become, how conversations are a rarity. At any given point, lakhs of people are tuned in but each one of them feels that the one RJ is speaking directly to him or her. Radio is a friend, a guide, an entertainer and a therapist." Ditto for ISHQ 104.8 FM RJ Sarthak who switched from television to FM radio early in his career. For him the radio is the medium of the moment. It's the theatre of the mind. "You say something, the listener says something, you laugh, they laugh. For that brief moment, you enjoy the camaraderie, the moment of pure joy, with no strings attached. You encounter such a brilliant cross-section of people who share what you like and you create something collaborative."

As the Urdu poet Noon Meem Rashid wrote and as Mahmood quotes so lovingly: Tamanna ji wussat kisko khabar? Indeed, who can know the expanse of desire. There may not be enough words to articulate the angst and the joy of what it means to be an Indian today, in ways big and small, in stories cataclysmic and catastrophic, but there are enough artists—self taught and trained by others—who are willing to try. To talk. To listen. To tune in. To sing. To repeat.