What’s in a Medium?

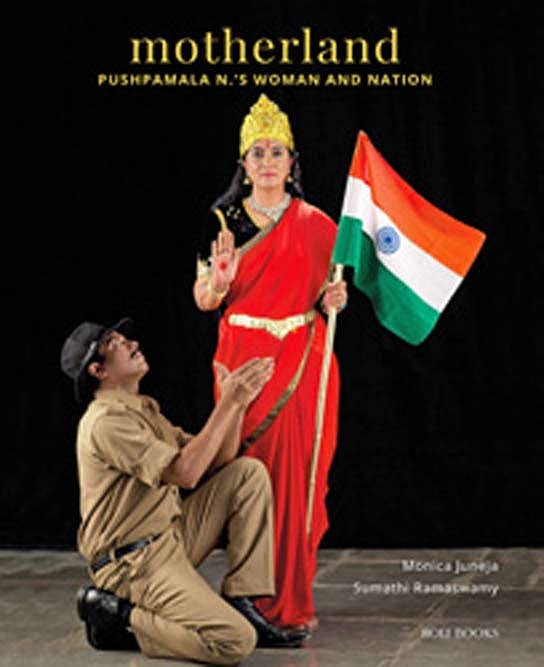

IN STUDIO PORTRAIT with Flag, Trishul and Om Flag (2009), Pushpamala N stands in a simple tableau. Dressed as the goddess Bharat Mata, she holds her implements in front of a small-scale, brightly painted, sharped-tooth lion, which is placed in front of the Indian flag, which in turn is pinned open on the floral textiles hung on lines as a backdrop. Layered and repetitious, every prop and costume falls approximately into the basic patriotic colour scheme of saffron and green, with liberal amounts of gold added in. Though immediately recognizable as a Bharat Mata image, there is no particular visual reference point, as there is for many of Pushpamala’s photo-performances. We should assume that this is deliberate, because the artist’s images include many more precise simulacra. This image, by contrast, imitates studio photographs in which ordinary people use sets and props to take on new personas. In many cases, the illusion is far from perfect; that does not seem to have affected the popularity of the practice.

As an inspiration for her performance photography, Pushpamala has cited her mother’s experience with similar sorts of make-believe, while acting in an amateur theatre club for women in Bangalore (present day Bengaluru). While she notes that her mother, Vanamala, was tall enough that she often took on male roles, the photograph the artist published is of her mother as Rani of Jhansi, the self-sacrificing warrior queen of the 1857 mutiny against British rule. Growing up in Bangalore, these performances were part of Pushpamala’s everyday life, as a middle-class form of popular mythological performance. The artist underscored that point by sharing with me a photograph of herself in a tableau, from her childhood, where she was playing the mythological figure Ahalya with three other children. They recreate a commonly represented moment of divine intercession, in which Lord Ram saves Ahalya from her husband, who is about to punish her by turning her to stone. Ram’s brother, Lakshman, and the sage, Vishwamitra, look on. The children in the photograph are all in costume, with Ram and Lakshman recognizable by their crowns and large bows, and Vishwamitra by his huge, grey wig and beard, sacred thread, and begging bowl. Young Pushpamala wears Ahalya’s white sari and flowers, kneeling prayerfully. All four children look serene and dutiful, carrying their iconographic signs and recreating familiar gestures, holding still for the shot.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The photographs from Pushpamala’s childhood must be just a few of hundreds of thousands of such images: some made by photography hobbyists at parties, some made in commercial studios chock full of costume options and others recording the temporary deification of children in sacred performances of epic stories. The kind of events that Pushpamala’s family participated in were clearly distinct from the Ramlila and other epic performances that have been the focus of academic scholarship. Here, we have an altogether looser and more worldly sense of play. This is something closer in spirit to a costume party, in which children and adults might take on a set of familiar roles, in a freeing masquerade. A woman takes on the role of a hero. A young child awkwardly impersonates an old man. A girl presents an ideal, virtuous version of herself.

And yet, while this tableau was likely just part of a fun family gathering, the choice of subject seems odd. Why on earth would adults ask children to recreate this episode? Ahalya was created by Lord Brahma, taken in as an orphan girl by the sage Gautama, then awarded by the god to the sage as a wife, a reward for his not taking advantage of her when she was underage. One day, after their marriage, Ahalya and her husband have sex, but then it turns out that the god Indra, besotted, had tricked her by assuming sage Gautama’s form. When sage Gautama discovers what happened, he angrily casts a spell to turn Ahalya into stone, setting up Lord Ram’s intervention. What does it mean for children to inhabit these roles, acting out a story of male sexual desire and female acquiescence? To find such photographs cute and harmless seems naïve, but to describe it as overtly dangerous seems histrionic. Neither option is terribly satisfying.

The photographs of Pushpamala as a child performer are not designed to yield to such questions. But the adult artist’s later recreations certainly are. They sit within the sphere of contemporary art, with its established modes of viewing and history of critique. They use artistic conventions to intervene critically in popular visual practices. Pushpamala’s photo-performances open up to scrutiny the act of dressing-up and posing for the camera, as well as the desire to recreate visual stories. They also open up the stories themselves to questions. As a whole, Pushpamala employs two major modes of practice in her work. In one, which has been the primary focus of her work from the Native Women in South India project onwards, the artist recreates an archive of visual references through performance and in the other, the artist indulges in, while critically appropriating, everyday forms of popular performance. These include the role-playing practices just described, but also, more significantly, our everyday inhabitation of gender roles. This essay traces this second mode from the first two of Pushpamala’s performance photography projects up to the Motherland series.

These two modes of work prompt different forms of viewing. In the first, knowledgeable viewers typically read or decode the artist’s work by paying close attention to the historical significance of the reference image. Pushpamala recreates images with care; her attention to details of costume and material culture often encourages in viewers a similar attentiveness, as they pick apart the elements of the image. The work not only depends upon but also adds to the viewer’s knowledge of visual culture. In that, it is similar to other works by artists associated with the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University, in Vadodara, Gujarat. Encouraged by artist KG Subramanyan to create forms of art that would resonate as critical interventions in everyday life, rather than simply in an autonomous history of art, it was common for artists associated with the faculty to document and/or collect visual culture. While each took a different approach, some, like Gulammohammed Sheikh, employed a strategy of visual quotation and recontextualization, bringing visual references directly into their works, while others, like Bhupen Khakhar, adopted popular pictorial strategies in their works. Pushpamala’s practice is exemplary of the broader approach of imbedding contemporary art in India’s layered and complex visual culture. Her photo-performance practice was developed alongside the growing interest in collecting popular art and ephemera, as well as the field of scholarship. Over the past two decades, the knowledge about the images she recreates has deepened considerably.

WORKS MADE IN the second mode tend to announce their construction, as in Studio Portrait with Flag, Trishul and Om Flag, with its contrast between the set’s decidedly non-spectacular nature and the perfectly composed performer-as-goddess, her costume, gestures and props correct. In other works of this more informally staged type, the artist assumes her guise and then improvises her actions. This is the manner in which the artist began to explore photo-performance as a medium, in the initial set of works in The Phantom Lady, or Kismet (1996-8) series. Working with her friend Meenal Agarwal in response to the curator Arshiya Lokhandwala’s prompt to create works in dialogue with cinema, Pushpamala performed as “The Phantom Lady”, wearing a costume that invoked the screen icon of 1930s, Fearless Nadia (Wadia) and, more distantly, the figure of Zorro. This image is reminiscent of Bhupen Khakhar’s faux advertisements in his 1972 catalogue, “Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God”, for which he posed as a somewhat effete babu, a cigarette model, and an international spy. While Pushpamala credits Khakhar’s playful, queer photo-performances as an inspiration for her work in the medium, her work captures this spirit most in images like the one from her first shoot as the Phantom Lady. In the photograph, she floats in mid-air, having jumped off the balcony of a slightly decrepit Italianate mansion. The image suggests an open-ended narrative—a chase, perhaps, or maybe just some fun—but the focus is on the figure, and the artificial and constructed nature of performance.

These more improvisational images offer ideal sites from which to consider Pushpamala’s engagement with performance as a medium. Pushpamala began her performance-based work at a moment in which ideas about the medium were profoundly shaped by the work of Judith Butler. Butler’s focus on the performative function of speech, on doing-by-saying, made possible an understanding of the constitution of gendered subjectivity through language. In her 1998 book Body Art/ Performing the Subject, art historian Amelia Jones very skillfully articulates the broadly emergent understanding of performativity to argue that performance art fundamentally troubles the distinction between subject and object. Focusing particularly on the work of Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, she builds a model in which feminist performance has the most to gain, analytically, from exploiting the medium’s possibilities. As the feminist-artist-subject is also the woman-art-object, at once actor and acted upon, in feminist body art/performance, the artist/woman’s subject-position is both made manifest and subverted—rendered false— through the act of articulation. For our purposes, it is important that Jones rejects the primacy of live performance and considers the oft-displayed records of performance as equally significant. Indeed, it is possible to see how a focus on the documentary evidence of performance would only further justify Jones’s point: held static, both photographs of performance and photo-performances expose even more clearly how the artist has placed herself in the role she inhabits, making visible the processes of objectification that she both imitates and undermines.

Although these fundamental ideas about feminist performance art informed Pushpamala’s work, they were perhaps less directly influential on her choices than a set of transdisciplinary and transnational debates that were emergent at around the same time. One important initiative sought to collect and publish women’s historical and contemporary writing, thinking very carefully about the relationship between authorship, expression and political agency. The small publishing house most closely associated with that trend, Kali for Women, also became the site of historical reinterpretation of colonial and nationalist debates about the so-called “women’s question”, meaning, the rolling set of issues through which the contours of women’s lives were shaped by colonial law and nationalist debate. In a series of landmark essays, historians established the manner in which a normative ideal of high caste, Hindu womanhood came to be seen as the site for the preservation of Indian tradition and identity. That current in turn allowed for the identification of an idealized and reified womanhood within Indian cinema, which informed a foundational set of works in film theory and history. These scholars, which included Pushpamala’s then-husband Ashish Rajadhyaksha and others in her social circle, grappled with how much female characters simply reflected male desire. The “good woman” character in Indian cinema, in particular, lacks subjective depth. The crucial underlying principle in all of these debates is the focus on narrative, and the manner in which the stories told about and by women constitute their understanding of female agency, or its lack, as well as women’s ways of being in the world.

In this context, Pushpamala’s photo-performances layer the already established feminist understanding of the capacities of the medium to subvert received notions of gender over these intellectual projects, in which the capacity for female agency was being excavated, represented and rethought. Pushpamala was immersed in film when she developed Phantom Lady, recapturing through that persona a relatively obscure and complex moment of Hindi cinema. The creation of Mary Evans, an Australian circus performer who married into a storied Parsi film family, the persona Fearless Nadia appeared in stunt films wearing outlandish clothing and wielding a whip. Her career, though illustrious, was short. As the generic codes of Hindi cinema began to solidify, the stunt-film genre and this character type was sidelined. Indeed, Fearless Nadia is everything that the typical cinema heroine is not. And so, from the point of view of the present (or even the 1990s), she is a highly subversive figure, presenting a neat counterpart to the Hindu womanhood projected on screen.

The artist underlined this contrast through an early companion project to Phantom Lady, the 1997 short video Indian Lady. She made the video as part of an Indo-Australian artist exchange Fire and Life, in which Pushpamala was paired with Australian artist Derrick Kreckler, whose work dealt with the Australian folk hero, Ned Kelly. In the thirty-second video, presented on a loop, the artist comes out from behind a painted studio backdrop of the city of Bombay (present day Mumbai). Smiling gaily, she looks coquettishly at the camera, her finger along her cheek, and dances back and forth before sashaying out of frame. Seemingly slight, the video pays extraordinary attention to costume and bodily gesture. To viewers at all familiar with the romantic song sequences commonly referred to as “running around trees”—in which the hero chases after a heroine who pretends to resist—it is clear what is being parodied. But just as in the 2009 Studio Portrait, viewers are given few cues to spark their associations. Isolated from her narrative context, questions emerge about how and why she is acting in this manner. It is fun and subversive, but the image maintains its open-endedness, preferring to ask rather than answer.

In later projects, Pushpamala placed film images alongside a wide array of visual cultural forms. Throughout, her work has retained its initial concern with rethinking agency, consistently offering an alternative, explicitly feminist artistic subjectivity that eschews the heroic demonstrations of virtuosity so prized in Indian modernist discourse. With this, and perhaps because of her working relationships with theatre and film, Pushpamala’s photo-performance works are both very densely referential and openly collaborative in process. Particularly in these more improvisational images, it is clear how much her practice is characterized by dialogue with other practitioners, who contribute various sorts of skills and forms of expertise to their making, even as the artist quite literally animates the work. And so, it is possible to consider how her process of working reinforces the role that narrative plays in the constitution of the self. What her work proposes is a decentralized and fragmented idea of personhood, in which one’s costume, gesture and context profoundly shape the course of one’s actions.

What, then, does it mean for the artist to perform Bharat Mata? Informed by performance art’s fundamental blurring of the distinction between subject and object, Pushpamala at once stages, takes on, and opens up an image of divine power to questions or comment. The 2009 Studio Portrait, in particular, finds its inspiration both in everyday practices of performance, in which children and adults participate in forms of masquerade both in and out of theatrical settings, and in sophisticated debates about gender and subjectivity. Her inhabitation of the figure of the goddess is quite precise, projecting calm beauty and determined power, but also offering herself to be viewed. As mentioned above, the tableau in which she stands is dramatically less convincing. That disjuncture is a gesture through which Pushpamala opens the image. It makes its meaning less determinate, offering the photo-performance as a space for deliberation, and an openness to critique, if not, necessarily, an explicit critique in itself.

(This is an edited excerpt from Motherland: Pushpamala N’s Woman and Nation edited by Monica Juneja and Sumathi Ramaswamy)