The War on Inflation

INDIA IS IN THE MIDST OF RESTORING macroeconomic stability. If one may add, with vengeance. On June 8, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) increased its policy rate, the repo rate, by 50 basis points, the second major increase since May. The overall increase is just 10 basis points short of a full percentage point increase. This is a step that has not been taken since the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014.

The Union government has also stepped up at the same time. After RBI announced a rate increase on May 4, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a slew of pricing and taxation decisions on a host of commodities on May 22. The goal of the fiscal and monetary authorities, acting in near unison, was to cool down the inflationary fire that threatened to engulf India in the wake of the war in Ukraine and the dislocations wreaked by two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. The breakdown in supply chains, the imperative to restore economic growth, and the massive surge in the prices of commodities from crude oil to foodstuffs and from intermediate goods serving as raw materials to steel, had begun to threaten macroeconomic stability in India.

When Sitharaman announced the re-jigging of excise and import duties on May 22, people at large only looked at the cuts in excise duties on fuels. While the scope of these excise and tax changes affected large parts of the economy, these were forgotten in the acrid Centre versus states debate on fuel tax cuts. It is these changes that have begun to have a cooling effect on prices.

Perhaps the best example in this respect is that of steel and steel products. In 2021, reeling from a pandemic-induced depression in growth, steel sales and prices hovered around ₹ 67,000 per tonne for hot rolled coil (HRC). By May this year, these prices had ratcheted up to ₹ 72,600 per tonne, an unbearable level for many steel consumers. These elevated prices were not just due to higher demand as the economic recovery set in but also due to a complex set of factors. For one, the prices of many raw materials used in steel production had gone up globally, making life difficult for steel producers in India. For another, demand for steel outside India was robust and exports were a very attractive option.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

Unwinding these effects required simultaneous action on different fronts. This is what the finance minister's announcement on May 22 did. From that day, import duty on anthracite/pulverised coal injection (PCI) coal was brought down from 2.5 per cent to nil. Import duty on coking coal was reduced to nil from 5 per cent and that on ferronickel to nil from 2.5 per cent. But, at the same time, the government imposed an export duty of 15 per cent on a variety of steel products. The results were predictable. By early June, HRC steel prices had fallen by roughly 8 per cent to around ₹ 63,000 per tonne. They are expected to further come down to ₹ 60,000 per tonne by July.

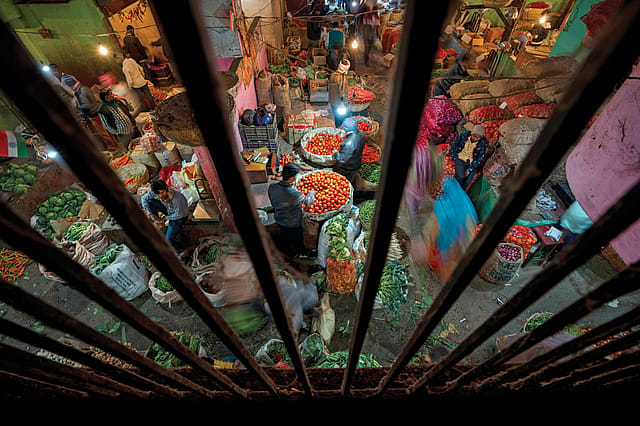

The story is repeated for commodity after commodity where the government has intervened to tamp down prices. Duty-free imports of 20 lakh tonnes of crude soybean oil and crude sunflower seed oil are expected to cool prices of edible oils, another price-sensitive consumption item. Cement prices have also begun to cool down. Import duties on raw materials used to produce plastics have also been slashed. The import duty on naphtha has been brought down to 1 per cent from 2.5 per cent; on propylene oxide to 2.5 per cent from 5 per cent, and on PVC from 10 per cent to 7.5 per cent. These being intermediate goods used in the production of other goods, their cascading effect on the reduction of prices is likely to be significant. Similarly, Sitharaman announced an additional subsidy on fertilisers of ₹ 1.10 lakh crore. This is in addition to the budgeted subsidy of ₹ 1.05 lakh crore for 2022-23. This is likely to blow a fiscal hole in the government's coffers but the calculation is a complex mix of food security and final output of various crops likely to suffer in case fertilisers are not available at reasonable prices. On June 6, the Union minister for chemicals and fertilisers, Mansukh Mandaviya, publicly stated that India has sufficient stocks of fertilisers to last until December this year. The "nano"-sized bags of urea and efforts to ramp up domestic production of complex fertilisers are another step to ensure that farmers get what they need on time.

Another good example, one for which the government has been criticised severely, is that of wheat. The war in Ukraine and the Russian blockade of Ukrainian ports in the southeastern part of that country sent global wheat prices spiralling north almost uncontrollably. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) tracks food prices globally through a variety of indices. FAO's composite Food Price Index (FFPI) shot up dramatically and stood at 157.4 in May compared to 128.1 in the same month last year. The cereal index came almost unhinged: 173.4 in May 2022 compared to 133.1 in May 2021.

This situation affected India as well. The second advance estimates of production for major crops for 2021-22, released on February 16, pegged wheat output at 111.32 million tonnes. This was expected to be a record yield, higher than the average wheat production of 103.8 million tonnes. India was expected to be the next big wheat exporter in the wake of the Ukraine crisis. Instead, disaster struck in March when a record-breaking heat wave hit north India. Wheat yields were now expected to go down anywhere from 10 to 20 per cent. In no time, domestic prices began rising fast. In April, wheat prices touched ₹ 2,100 per quintal, up from ₹ 1,975 per quintal in February. For comparison, wheat prices in July last year were around ₹ 1,750 per quintal. These are phenomenal increases in a food item in which India prides itself as not just self-reliant but also surplus.

Unsurprisingly, the Union government banned wheat exports on May 13. This step attracted unusual ire from the policy community and the wider commentariat. The anger was due to an attractive option to earn from exports and allegedly over India backing away from its commitments. No one bothered to examine the consequences of sustained increases in wheat prices, economically and politically. But the government did what was necessary.

BUT BEYOND THE immediate goods and commodities, the inflation story for the most part revolves around RBI's extraordinarily accommodative stance to ensure that growth recovered quickly after its precipitous decline in the wake of the lockdowns due to the pandemic.

To that end, the central bank kept its policy rate, the repo rate, unchanged for the entire duration of the pandemic at 4 per cent. While the repo rate had been brought down steadily over the years from a high of 7.75 per cent in March 2015, the two-year period between May 2020 and May this year was probably one of the longest stretches in recent memory with such a low rate. These rates were consistent with the low level of inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in those years. In 2017, the rate of inflation was 3.3 per cent; in 2018, it was 3.95 per cent and in 2019, 3.72 per cent.

That was not all, if one reads the minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) for the last one year, RBI resolved to keep its monetary stance "accommodative" during this entire period. This meant the central bank was not likely to tighten monetary policy and would maintain its policy rate unchanged.

Even as RBI was ensuring that money supply did not come in the way of economic recovery, inflationary pressures were building up steadily. In 2020, CPI inflation jumped to 6.62 per cent, up by almost three percentage points over 2019. But give or take a percentage point, these figures were still within the band deemed acceptable by RBI. Right until May this year, the overwhelming concern for MPC was ensuring the recovery of growth. The voting record of MPC attests to the unanimity on this goal.

But somewhere along the path, the central bank had lost the plot. During the period when RBI kept the repo rate unchanged, various editions of its own Inflation Expectations Survey of Households (IESH) pointed to a very different picture. A year after the pandemic, from May 2021, it was clear that inflationary expectations—the perception of individuals about future inflation—were hardening. In May 2021, surveyed individuals felt that inflation would rise to 10.9 per cent. By December of that year, this went up to 12.6 per cent. Such surveys are not a reflection of actual inflation but are a very good indicator of the direction of inflation—up or down—and that signal was unambiguously clear: individuals expected inflation to go up. But that did not alter the central bank's policy preferences and all along RBI kept the policy rate unchanged.

It is not as if the matter did not enter MPC's deliberations. One member, Jayanth Varma, repeatedly emphasised the dangers of inflationary expectations coming unhinged and making inflation the problem that it finally turned out to be this year. In the MPC meeting from June 2 to 4, Varma issued a statement saying, "The MPC must be sensitive to the risk that inflation expectations could become entrenched if inflation remains elevated for too long." He also warned that MPC's ability to keep inflation in check depended on its "hard-earned" credibility. He kept on repeating this message until he voted against the accommodative stance of the central bank at MPC's meeting in October last year.

But all along MPC continued to vote unanimously to keep the repo rate unchanged at 4 per cent. This was until early May this year when RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das made an "off cycle" announcement of a 40-basis point increase in the repo rate. But the announcement was late. By then retail inflation (CPI) had remained beyond RBI's 2015 mandate of the 4 to 6 per cent band. Worse, the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) had remained in double digits since last year. CPI and WPI measure inflation for different baskets of goods. A better measure is based on what is known as the GDP deflator. Technically, the GDP deflator measures the level of prices of all new final goods and services produced in an economy. It is a much wider measure of inflation.

The GDP data for 2021-22, released on May 31, shows the GDP deflator at 9.96 per cent, indicating that inflation was not only higher than what RBI had estimated for the year but had also spread to a much larger set of goods and services. (Some private sector economists pegged the GDP deflator even higher at 10.8 per cent, closer to what respondents said in various IESH rounds). The GDP deflator has gone up from 5.6 per cent in 2020-21 to 9.96 per cent in 2021-22, an increase of 4.36 percentage points.

At this point—as indicated by RBI's further increase in the repo rate on June 8—the central bank had no option but to increase the policy rate. Given the generalised nature of inflation as seen from the rapid increase in the GDP deflator, there is no other option for the central bank but to increase its policy rate steadily. Until about a month ago, it was an open debate whether RBI should even contemplate rate increases as inflation was due to a massive surge in prices of commodities that were not amenable to control via monetary policy. But this was hardly a debate as recently argued by Sajjid Chinoy, a private sector economist who is also a part-time member of the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council (EAC). In an essay in Bloomberg Quint, he argued: "In April, prices of almost 60% of the 300 items in the CPI basket were growing at an annualised monthly momentum of over 6%. This used to be less than 30% back in 2019."

SLOWLY, THE CENTRE is getting its act together. Fertiliser supplies have been augmented and are claimed to be sufficient until December. The flip-flops in the export of commodities like wheat—that have led to strong criticism—notwithstanding, the key objective of the government is to ensure that prices of wheat and other essential food items don't get inflamed, the last thing that is needed in managing supplies in a supply chain-broken world.

No one could predict the complex effects of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine that followed before Covid was safely behind us. One of the predicted effects of the pandemic was reduction in demand. That led to vociferous demands for a stimulus on the part of the government. In no time, the war in Ukraine led to the very opposite situation where red-hot prices are giving headaches to policymakers across the world. Compared to a vast majority of countries, India is much better off and self-reliant in key supplies like food and manufactured goods. The price vortex it has faced in the past months is, in part, due to a commodity price shock of items like oil, coal and fertilisers that it is forced to import. RBI and its MPC have been roundly criticised for falling "behind the curve". But all along their objective was very clear: ensuring that India returned to its growth trajectory, an objective that is far more important for the economic and political future of the country.

The war in Ukraine has entered its fourth month. These months have been turbulent for commodities and other downstream products. Basic goods like oil and food are now in a supply shock that seems to have no end in sight. Countries that until the other day could pick and choose their suppliers are now desperate for wheat, coal, iron ore and a host of other items. While the effects of this shock are felt most immediately by consumers, there are bigger problems for governments that are trying to undo the effects of the pandemic. India was no exception. For a long time it was thought that a loose monetary policy was the solution to the problem. This year it discovered, painfully, that this was not so. The one lesson of the combined external shock of the pandemic and the war is the need for a better, coordinated, mix of monetary and fiscal policies. In the uncertain times ahead, this is the best course of action.