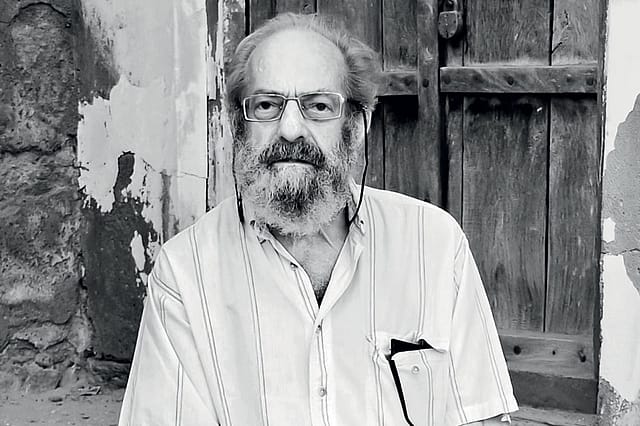

Paul Brass (1936-2022): The Chronicler of South Asia

PAUL BRASS, WHO DIED after a long illness aged 85, was a scholar par excellence of modern India and a pioneer in the fields of ethnic politics, nationalism, and collective violence. He was trained in government and political science at Harvard College and the University of Chicago. Throughout his professional career, he was anchored at the University of Washington, Seattle, where he taught political science and international studies.

Brass first visited India in 1961 while still a graduate student of political science at Chicago. What began as a doctoral project would turn into a lifelong intellectual pursuit, an academic career spanning more than six decades, over a dozen books and scores of articles. In his wide-ranging oeuvre, Brass grappled with some of the most pressing questions facing modern nation-states: how identity politics or collective violence shapes and is shaped by, in turn, the everyday life of the people and institutions that make the nation. He didn't offer quick answers to these ever-shifting dynamics of politics. Instead, he would make this broad enquiry the basis of his long-term ethnographic engagement in northern India, the empirical foundation upon which he built some of the most original works on the political life of violence. It is often said that he chose Uttar Pradesh as his field site. Yet, looking back, it seems that it is more likely Uttar Pradesh chose him. He returned regularly to the state, especially the city of Aligarh, for extensive periods over half-a-century to draw rich accounts of the many political lives of independent India.

Brass leaves behind a rich body of scholarship which testifies to this long-term relationship with northern India. One of the most prolific writers of his generation, he authored a number of groundbreaking books including Factional Politics in an Indian State: The Congress Party in Uttar Pradesh (1965); Language, Religion, and Politics in North India (1974); The Politics of India Since Independence (1990); Riots and Pogroms (1996); Theft of an Idol: Text and Context in the Representation of Collective Violence (1997); The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India (2003); and a three-volume magnum opus on Chaudhary Charan Singh entitled The Politics of Northern India 1937-1987 (2011-14). It is difficult to offer a full account of this vast range and depth of scholarship produced over several decades. But what runs through this body of work is a continuous effort to make sense of the nature and effect of communal violence in Indian politics. Why do communal riots persist in India? What explains the occurrence of violence in some places and not others? And how are power relations transfigured in the shadow of violence?

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

These overarching questions are what led him to one of his core arguments: that communal violence is a complex production of "institutionalised riot systems." The riot system, as he laid out, comprises the rehearsal, staging, and interpretation of violence as "spontaneous" retaliation against presumed threats from the other community. Moving beyond the explanations of communal violence as sudden and unpremeditated, he drew attention to the work of riot specialists or agents he called "fire tender"— those who keep the embers of communal animosities alive—and "conversion specialist"—who turn a small incident into a full-blown riot by inciting the crowds or indulging in violent actions. This activation of tensions/prejudices into violence at critical moments, he suggested, is what potentially led to communal polarisation and consolidation of blocs amid an intensification of electoral/political competition. As crucial as the production of violence was the competition to interpret and classify the event of violence as a riot, an exercise that made visible the role of police and media in how the event was recorded and reported. For Brass, this detailed forensic analysis of violence only opened further questions: If the mechanisms of riot production were well understood by the local authorities, media, and the public as such, then why do riots continue to occur? The Brass thesis, as it came to be known, offered an instrumentalist position on riots as rational orchestrations which seek to consolidate political constituencies. This explanation was by no means a rejection of cultural and psychological factors of how communal identities were created and nurtured, or how an alternate archive of knowledge was created about the "other" community. Instead, he foregrounded how such knowledge was put to work to transform arguments into violence. If riots continue to persist, he argued, it is because of their functional utility to generate political benefits. Perhaps one of the most vital contributions of Brass was to make familiar a vocabulary of violence that was both universal and specific to South Asia. He not only delved into the local politics of classifying violence but also located communal violence in a wider genealogy of forms of collective violence.

Based on a wealth of primary empirical data, these observations about the nature of "riot politics" were central to framing key debates in Indian history and politics. A memorable example is the Brass-Robinson debate, a series of exchanges between Paul Brass and Francis Robinson, a British historian specialising in South Asia and Islam. In his masterpiece Language, Religion, and Politics in North India, Brass explained the emergence of Muslim separatism as a rational bid to keep power in modern politics that was shaping up under colonial rule. For Robinson, this instrumentalist view underestimated the role of Hindu and Muslim revivalism and cultural symbolisms that forged collective fears and desires. What was remarkable about this exchange was not just the arguments but also the absence of acrimony between two scholars who held contrasting views.

His work has indeed been influential in shaping an entire generation of scholars of Indian politics. Witty, warm and generous, he seemed to take delight in sharp arguments, even disagreements, also when they came from junior scholars. I experienced this first hand in 2004. Paul was on my PhD defence committee, a scholar of repute who was also known for not holding back stinging criticism. It was an unnerving prospect especially since I was to present my thesis in a public defence. As it turned out, Paul asked sharp questions but also welcomed equally sharp responses, including disagreements. This kind of intellectual engagement and generosity is what drew junior scholars to him from far and wide. I was still a postdoc when I published my first book (an edited volume) on religion and politics. He not only gave helpful advice but also contributed an essay to the volume. He remained supportive of newcomers venturing into the maze of academia.

Paul Brass will be deeply missed, but his name will endure, thanks to his stellar studies on one of the most crucial periods in the history of the world's largest democracy.