Naval Mutiny and the War on Memory

ON FEBRUARY 18TH, 1946, sailors or ratings of the Royal Indian Navy mutinied. They were inspired by the heroism of the Azad Hind Fauj. But their anger was sparked by terrible service conditions, racism, and broken recruitment promises. In less than 48 hours, 20,000 men took over 78 ships and 21 shore establishments, and replaced British flags with the entwined flags of Congress, the Muslim League and the communists.

The British panicked and announced a Cabinet Mission to discuss the modalities of transfer of power. Indian troops refused to fire on the ratings, and the mutiny sparked revolts in other branches of the armed forces. People who thronged the streets of Bombay in support were incessantly fired upon resulting in over 400 deaths and 1,500 injured.

To quell the rebellion, the British commanded the powerful warship HMS Glasgow to sail rapidly and ordered low sorties by RAF fighter planes. In retaliation, the ratings trained the guns mounted on the captured ships towards the shore, threatening to blow the Gateway of India, Yacht Club and the dockyards.

As violence escalated, angry telegrams flew between the British prime minister and the viceroy’s office. While the communists flamed the ratings, Congress and the League pushed them to surrender, promising they would not be victimised. Shamefully, even after Independence the governments of India and Pakistan refused to honour those promises.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The mutiny caused public disagreements between Gandhiji and Aruna Asaf Ali, and between Sardar Patel and Nehru. As the last war of independence it hastened the transfer of power. Yet, this seminal event, which inspired songs, art and theatre, has been edited out of the popular narratives of the freedom movement.

***

ON MARCH 29TH, 1965, a Bengali play by Utpal Dutt, Kallol (literally “commotion” or “hubbub”) hit the boards at the legendary Minerva Theatre, on Beadon Street in North Calcutta. Dutt, a staunch communist, had dramatised the naval mutiny of 1946, taking it upon himself to act the part of Rear-Admiral Sir Arthur Rullion Rattray, Flag Officer Commanding, Bombay, who was one of the villains of the piece. The legendary Tapas Sen was director of lighting and Samir Majumdar, the assistant director.

The play lived up to its name as thousands lined up for tickets, causing pandemonium. Every show was a full-house. Majumdar recalls: “It was one of the finest productions. Utpal Dutt had created a wonder, the ship HMIS Khyber, was shown sailing in water on the stage.”

The play was highly critical of the role played by Congress and the Muslim League, depicting famous politicians as duplicitous, and highlighting their role in persuading the young, nationalistic ratings to surrender. Dutt had deployed his gifts of satire masterfully, ridiculing stalwarts like Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

Congress, under Chief Minister Prafulla Chandra Sen, ruled West Bengal at the time, and even 20 years after the actual event, the party tried to stall the production. They did not have the courage to ban it. But there were attempts to disrupt it by throwing bombs and sending goons to prevent people from entering the hall. The Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPM, countered this by putting a ring of volunteers around the venue to ensure smooth entry.

In his book, Towards a Revolutionary Theatre, Dutt later wrote, “Workers from the factories and students of several colleges took turns to stand guard outside the theatre… Youth Congress strongmen who had come prepared to attack the theatre, beat a hasty retreat seeing the CPM bandobast. Comrade Subhash Chakraborty (later sports minister of West Bengal) led the protecting volunteers at Minerva…

“Under pressure from Congress, no newspaper or periodical published news or reviews. The theatre critic of Ananda Bazar Patrika (ABP), a pro-Congress paper, bought tickets and smuggled himself in. ABP wove a review centred around one question: Why has the play not been banned immediately? But as the crowds at the box office grew larger and larger, ABP lost its sangfroid and wrote an editorial, calling for a social boycott of the actors and technicians.”

The Statesman was the only newspaper that praised the play in its review. It also published a sarcastic opinion piece headlined ‘The Mutiny on Beadon Street’. Dutt writes, “One day, all newspapers excluding the Statesman, refused to print our advertisements. That they were acting in concert and under instructions from the Congress bosses and police chiefs was obvious to all.”

To counter the absence of media, CPM volunteers made posters and pasted them across Calcutta. Some of these read in Bengali, “Apni kon dol ey—jara Kallol dekhechhey na jara Kallol dekheini”, which roughly translates as “On which team are you—those who have seen Kallol or those who haven’t?”

Street corners across Bengal boldly displayed posters saying “Cholchhe, Cholbe”—whatever is happening, will carry on happening—in an apparent reference to attempts to stop the play. That slogan has since been used in every, yes every, sort of demonstration in Bengal. Cholchhe, Cholbe in Bengal became like Inquilab Zindabad elsewhere.

Dutt was arrested in September 1965. He was picked up in a midnight raid and detained without trial in the Presidency Jail. He was only released in March 1966, in an event celebrated with much fanfare and a special performance of the play.

But while Congress did not succeed in bringing down the curtain on Kallol, it did succeed, over the decades, in downplaying mentions of one of the most important and seminal events of the independence struggle. Instead of being enshrined in public memory alongside the Salt March, Jallianwala Bagh, etcetera, the naval mutiny of 1946 tends to be relegated to just a footnote, except in scholarly works written by historians, for the benefit of other historians.

DESPITE THE DISDAIN shown by the political class, the ratings were openly supported by the common man and by the intelligentsia. Creative groups, largely Left-leaning, aligned themselves openly with the strikers. Despite the official disapproval, echoes of the mutiny seeped into literature, art and culture.

The Indian People’s Theatre Association or IPTA had been formed in 1943, three years before the naval uprising. The IPTA was at the forefront of communicating the spirit of freedom through its cultural prism. The founding members included Utpal Dutt, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Balraj Sahni, Pandit Ravi Shankar, Ritwik Ghatak, Salil Chowdhury and Prithviraj Kapoor.

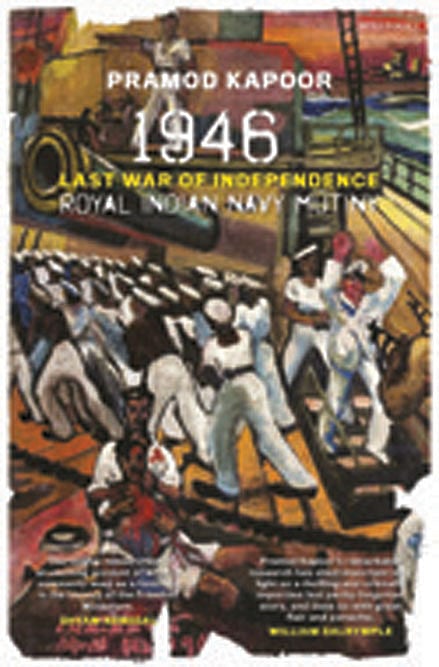

They not only supported the Ex-Services Association as a group but also lent their individual voices in support of the mutiny. In Karachi, AK Hangal was arrested for protesting against the firing on the sailors. The famous artist Chittaprosad (whose painting is used as the cover of this book) displayed his paintings at a rally supporting the strikers. His ink drawings and prints on the mutiny were profusely used by the Communist Party paper, the People’s Age.

Salil Chowdhury’s ‘Dheu Utchchhe, Kara Tutchhe (The waves of freedom are rising. The shackles of bondage and slavery are starting to crack)’, the song written in July 1946, barely four months after the mutiny, resonates even 75 years later.

One of the most poignant episodes during the naval uprising was the sight of ratings with their heads covered in white shrouds after taking control of the ship HMIS Kathiawar, and reciting Josh Malihabadi’s famous lines:

Kaam hai mera taghyur, naam hai mera shabab,

Mera Naara, Inquilab, Inquilab, Inquilab…

(My mission is change, my name is youthfulness/ My slogan is Revolution, Revolution, Revolution)

Sahir Ludhianvi also wrote powerful verses about the uprising:

Yeh jalte hue ghar kiske hain, yeh kat te hue tan kiske hain,

Takseem ke andhe toofan mein, Lut te hue gulshan kiske hain,

Badbakht phizayen kiski hain, barbad nashe man kiske hain,

Kuchh ham bhi sune, humko bhi suna, Ye rahkar-e-mulk-o-kaum

bata, Yeh kiska lahu hai kaun mara.

Woh kaun sa jazba tha jis se, Farsuda-e-Nizame jeest hila,

Jhulse hue veeran gulshan mein, ek aas ummeed ka phool khila,

janata ka lahoo faujon se mila. Faujon ka lahu janata se mila.

(What passion it was that made a moth-eaten system quiver/What passion it was that caused a flower of hope to bloom in this dreary desiccated land / What passion it was that mingled the blood of people with the armies, the blood of armies with the masses.)

The naval mutiny is also referenced in Bhowani Junction, a famous novel later turned into a multi-starrer movie, written by John Masters, a British Indian Army officer. Salman Rushdie, in his novel The Moor’s Last Sigh also devoted a large chunk to the mutiny. Amitav Ghosh’s The Glass Palace wonderfully details how young sons of peasants joined the navy at the beginning of World War II and then rebelled.

Utpal Dutt was so proud of the play, he named his home Kallol. The play ran for a record 850 shows. According to Samik Bandhopadhyay, a close associate and friend of Dutt, “A massive rally was held at the Maidan (after he was released). A special stage was set up to show a truncated version of Kallol.” Jyoti Basu, Harkishan Singh Surjeet, BT Ranadive were present at the performance. The day was called the Kallol Vijay Utsav.

Two massive performances in the most extraordinary settings were produced after Utpal Dutt’s death in 1993. An offshore set, which moved with the waves, was specially fabricated on the river Hooghly. Then in November 2005, over 50,000 people watched the play at Salt Lake Stadium in Kolkata.

The stage resounded with cries of “NO SURRENDER” every time it was staged.

(This essay draws on Pramod Kapoor’s new book 1946: Last War of Independence: Royal Indian Navy Mutiny)