The Rani of Jhansi’s Journey to Eternity through Art

THE PRINTED TEXT, I have discovered as a university teacher over the course of three decades, is increasingly but a foreign object to most students—even at allegedly world-class universities. Any reading is too much reading for some of them, though practitioners of the visual arts often complain that the culture of the modern West was shaped predominantly by the culture of the text and that the written word still reigns supreme. Some, having in mind the Sanskrit tradition, might be inclined to argue that the same could be said of India. At any rate, what scholars term the “visual turn” started to gain prominence in the 1990s and signalled a shift in humanistic scholarship and the social sciences towards the visible. The visual, however, is not merely a matter of apprehension of the phenomenal world by the naked eye, but rather also points to socially constructed experience and the conditions under which social experience becomes possible. As a student of the anti-colonial movement, I now recall that Indian history school textbooks, such as those produced by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), were almost entirely bereft of art work, and the narrative of the “freedom struggle” in even the vast majority of scholarly histories is presented purely in text. In recent years, several scholars, most eminently Chris Pinney, Sumathi Ramaswamy, and a few others, have turned to formerly unexplored ‘archives’—indeed, in work of this sort, one has to create an archive of one’s own—and treated images not merely as supplementary to the text but rather as shaping a narrative of their own.

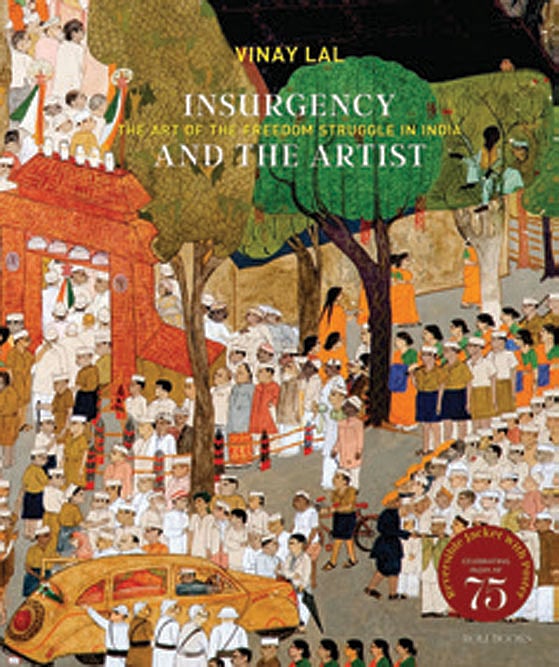

As a historian, especially of modern India, I have long wondered how artists who were contemporary to the freedom struggle responded to the anti-colonial movement. Just what was meant by ‘art’ and the ‘artist’, especially in the late 19th century or in the first decades of the 20th century, are vexing questions though it will not be possible to delve into them in detail at this juncture. The market for art in Europe was already well-developed by at least the mid-19th century and involved a complicated matrix of painters, sculptors, consumers, patrons, agents, art critics, museologists, gallery owners, conservators, and suppliers of art materials. One could justifiably speak of the vocation of the ‘artist’. Nothing like this was even remotely the case in India. What counts for ‘art’ is a wholly germane question even today: in the course of writing my book Insurgency and the Artist: The Art of the Freedom Struggle (Roli), it became apparent that most scholarly work on the art of the anti-colonial movement has thus far been riveted to what we might call “nationalist prints”. These were produced at workshops in cities such as Kanpur, Calcutta, Bombay, and Lahore, but little is known about these prints. No one would have even deigned to call them art until around two decades ago. These “bazaar prints”, as they are otherwise known, are akin to minor discourses; they have generally been viewed as ephemera, inconsequential, far more like advertisements than oil paintings: they are the flotsam and jetsam of the art critic’s world. Such prints, however, yield extraordinary insights into the freedom struggle, for instance, in showing how printmakers drew upon the vast lore of the mythic material that is the inheritance of nearly every Indian—stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, the large number of Puranas—in making the freedom struggle come alive even for Indians who were illiterate and far removed from the world of the text, print culture, and formal schooling. There was, moreover, far more to the anti-colonial movement than these prints, and in fashioning my own archive I stumbled upon the work of obscure or largely overlooked artists such as Babuji Shilpi, SL Parasher, MV Dhurandhar, and Zainul Abedin.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It is a similarly difficult question to assess what might justly be encompassed under the rubric of the “freedom struggle”. The coming of Gandhi, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay was to write in her memoir, virtually obliterated everything that had preceded him: in her words, “To those of my generation the real political history of India begins with the Gandhi era.” But artists and printmakers nevertheless found many other subjects, as their treatment of Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, demonstrates. The celebrated Bengali writer, Mahasweta Devi, whose vast oeuvre of novels, short stories, plays, and essays offered a dazzling and robust account of the lives of women, Adivasis, lower castes, and the downtrodden, was a lifelong admirer of Lakshmibai. As a young woman, she was smitten enough with her to write one of the first biographies of the Queen of Jhansi who, though very much a part of the lore of the Indian nation, had scarcely been a subject of serious historical inquiry. One can imagine why the Rani of Jhansi’s life may have been inspiring to Mahasweta, as it has been to so many women—and men. Sumathi Ramaswamy has noted the paucity of women in Indian nationalist art: though the oppressed nation itself is idealised as Bharat Mata, “Mother India”, she argues that the narrative of Indian nationalist art is largely framed around “big men”. These “pictorial big men”, she argues, visually endorse “a prevailing truth about nationalism as a masculinist project, fantasy, and hope.”

There is, to be sure, the occasional print of Kasturba, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, or Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, and more often of Sarojini Naidu, but the salience of Ramaswamy’s observation cannot be denied. Still, her invocation of the phrase “big men” is curious if only because the ‘big man’ has a history all his own: among political scientists, the “big man syndrome” has long been used to explain the trajectories of post-colonial states, especially in Africa, though the idea has also been used in reference to the likes of the Haitian dictator, François Duvalier, and Saddam Hussein. It is almost invariably used to refer to political leaders with pronounced authoritarian tendencies, but there is nothing to suggest that Ramaswamy had this indictment of Indian ‘big men’ in mind. Moreover, I wonder if the emphasis should equally be on “big” as on “men”: nationalist art has gravitated towards the commanding figures, rather than towards subalterns, the working class and peasants, and the marginalised. It has had little use for the tillers of the soil and all manner of ‘small men’.

If there is a ‘big woman’ in nationalist art, it is surely the Rani of Jhansi. In north India, at least, generations of schoolchildren grew up with Subhadra Kumari Chauhan’s poem on her with its famous refrain “Bundeley Harbolon key munh hamney suni kahani thi, / Khoob ladi mardani woh to Jhansi wali Rani thi (From the mouth of the Bundelas and the Harbolos we had heard the story, / This gallant manlike fighter was none other than the Rani of Jhansi)”. She was born as Manikarnika (“Manu”) on November 19, 1828 to a Marathi Brahmin family in Varanasi. Her mother passed away when she was but four years old; her father, Moropant Tambe, worked as a priest for Peshwa Baji Rao II in Bithur, instructing young boys in the scriptures. Vishnu Bhatt Godshe Versaikar, whose contemporary account of the events of 1857-59 was published some decades later, observed that Chhabeli (meaning the bird mynah), as Manu was affectionately called, was left unattended and started playing with boys, developing a “liking for boyish games”. “Once in a while,” Mahasweta Devi was to write, “she also got a chance to go horse riding. She often had boys for playmates because she was spirited and rambunctious by nature.”

Lakshmibai’s companions may have included Nana Sahib and Tantia Tope, two future leaders of the revolt of 1857. Sometime around 1890, a Jaipur artist, working in the style of the atelier of the court of Maharana Ram Singh II where the use of bright colours was common, drew an imaginary portrait of the young Lakshmibai astride a galloping horse, her right hand clutching a javelin. The rich brocade work on her tunic (angarakhi) and the similarly lavish jewellery adorning her horse suggest that the artist had in mind the girl who had already been enthroned as the Rani of Jhansi. Mahasweta Devi describes her as one of the most renowned “connoisseurs” of horses in north India, and no equestrian challenge was too great for her; indeed, rare is that print of Lakshmibai which does not suggest her fondness for horses and her adeptness in handling them. A Chitrashala print of Lakshmibai, from around the late 1880s, may have, in this respect, set the trend (see figure).

WHEN SHE WAS not quite 12 years old, Lakshmibai was wedded to Gangadhar Rao, the ruler of Jhansi who had been in search of a bride from a south Indian Brahmin family. The son she bore him nearly 10 years later, Damodar Rao, lived not more than four months. The night before Gangadhar Rao died in November 1853, they adopted an eight-year-old boy, Ananda Rao; however, the British refused to recognise the legitimacy of the adoption. Dalhousie, then the governor general of India, invoked what historians have termed “the doctrine of lapse”, whereby a native kingdom was viewed as having forfeited any right to an independent existence upon the failure of the ruler to produce a biological heir to the throne, and Jhansi was absorbed into British India. However, as central India became imperiled in 1857, the British restored her power and then sought her assistance. When about 60-65 Britons, including women and children, were massacred in Jhansi the British held her responsible. The Rani rejected the charge; to the contrary, argues Mahasweta Devi, Lakshmibai was moved to help the British from “an innate feeling of solicitude”. To the mind of Thomas Lowe, a British army doctor who penned a narrative at that time, the Rani was the “the Jezebel of India”, a false prophetess who sent her people like lambs to slaughter. When Jhansi was invaded by Orchha and Datia, native states that had allied themselves with the Company, the Rani implored the British for help but her call went unheeded. She had fallen afoul of the British; at this time, she threw her lot in with the rebels.

In late March 1858, Sir Hugh Rose, commander of the British forces, besieged Jhansi. Our Brahmin witness, Versaikar, reports pitched battles and states that the “Rani personally supervised the site of all attacks”; dressed in male attire with a sword in her hand, she would do the “rounds to boost the morale of her men”. A lithograph from around 1890, again from the Chitrashala Press in Poona, shows her rather in a cavalrywoman’s uniform, but she is heavily armed and her face suggests quiet but fierce determination. At last, the defences of Jhansi broke: “One must praise the lone woman, our great Rani,” Versaikar wrote, “who roamed the fort and defended the city constantly for eleven days while the British bombarded us.” An English writer offered a more vivid account of the Rani’s heroic defence of her kingdom which the publishers of Vinayak Savarkar’s 1947 Indian edition of his book on the “First War of Indian Independence” illustrated with a painting in vivid colours and the image of a fearless warrior who seems to leap from the page (see figure): “the beautiful Ranee… led her troops to repeated and fierce attacks and though her ranks were pierced through and were gradually becoming thinner and thinner, the Ranee was seen in the foremost rank, rallying her shattered troops and performing prodigies of valour. The dauntless and heroic Ranee held her own.” Lakshmibai took to the fort after the city fell but there was to be no respite from the relentless assault and just days later she decamped with her son, father, other kinsmen and some retainers for nearby Kalpi, where she joined forces with Tantia Tope. It is said that her favourite horse, Badal, died during her flight, but what is likely the most enduring image of the Rani of Jhansi seems to capture the moment when she jumped on her galloping horse. In a print L Pednekar published from Bombay, her young son clutches her as the turbaned Rani, dressed in a bright red sari, brandishes her sword in defiance (see figure).

Unable to hold Kalpi, which fell to the British in late May 1858, the Rani, Tantia Tope, and others took to Gwalior. It is in the capital of the Scindias that Lakshmibai took her last stand before succumbing, sometime on or around June 17, to the enemy under circumstances that remain unclear. Her legend was set in motion very soon after her death, judging at least from the fact that a painting by an unknown artist, where the Rani engages with British troops, is dated to around 1860 (see figure). She dominates the picture: not only is she drawn larger than the men but she alone appears to sit majestically astride a horse. The other Englishman on a horse seems a little off balance, and his horse has its face turned away from the action; another Englishman has fallen on the ground, the blade of the sword wielded by one of her swordsmen at his neck. In the heyday of nationalism, in the era of Gandhi, the Rani of Jhansi was not forgotten. Picture merchant Shyamlal Sunderlal of Kanpur issued a print by Ramshankar Trivedi, captioned ‘Jhansi ki Vir Kshatrani (The Brave Woman Warrior of Jhansi)’, which takes elements from the earlier prints: there is the Rani with her adopted son tied to her back, spearing the Englishman on the ground. Her legend spread far and wide: some in Europe likened her to Joan of Arc, and the Coast Hindustani Association of San Francisco, in its periodical The United States of India, celebrated the anniversary of the beginning of the rebellion in May 1857 by a front-page spread in its May 1926 edition featuring a drawing with the headline, ‘Rani Lakshmi Bai: Heroine of the War of Independence of 1857’. A heroine, indeed: ‘Khoob ladi mardani woh to Jhansi wali Rani thi’; or, as Sir Hugh Rose, her vanquisher, put it, “She was the bravest and best man on the side of the Mutineers.” Gandhi strove for androgyny, and so found the best of the woman within him. Lakshmibai, so goes the story, was the only man of the Indian Rebellion of 1857: thus is the wondrous story of our freedom struggle.