Sultan of the Sublime

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INDIAN ART THROUGH FIVE MASTERPIECES – PART 3

Ibrahim Adil Shah II, who ruled the central Indian kingdom of Bijapur in modern Karnataka, was an erudite scholar, lute player, poet, singer, calligrapher, chess master and an aesthete.

Since he came to the throne in 1580, he oversaw a remarkable explosion of artistic activity, attracting to his court the greatest painters and poets of his day, from as far afield as Abyssinia, Turkey and Central Asia. These included Zuhuri, the Persian poet-laureate, who he lured all the way from Isfahan, and one of the most celebrated artists of the Mughal court, Farrukh Husain, who travelled to Bijapur from Shiraz, via the courts of Kabul and Agra. But an itinerant Dutch Mannerist painter named Cornelis Claesz de Heda who arrived at his court in 1608 was certainly Ibrahim's most exotic catch. As soon as word reached court that a European painter had crossed the border from Goa, Ibrahim summoned him straight to his capital.

'When I came here to the court,' Cornelis later wrote, 'the King, as a great lover of the arts, let me come immediately before him. The King said he had long wished for a painter from our land, and had me clothed with great honour.' Cornelis was delighted by the enthusiasm of the sultan who he described as 'very mild and kind-hearted… and having good judgement in matters of aesthetics.'

Shortly before Cornelis arrived in Bijapur, Ibrahim had changed the name of his capital from Vijayapur, City of Victory, to Vidyapur, City of Learning. According to the chronicler Rafiuddin Shirazi, during his reign the libraries of Bijapur had swelled with painted manuscripts as Ibrahim had 'a great inclination towards the study of literature and he had procured many books connected with every kind of knowledge. Nearly sixty men, calligraphers, gilders, book binders and illuminators were busy doing their work the whole day in the library.'

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The atmosphere of languid, courtly freethinking that Ibrahim encouraged is reflected in the Bijapur school of miniatures which underwent its Renaissance under Ibrahim's patronage. In these wonderful otherworldly images, water drips from fountains as courtesans as voluptuous as the goddesses of south-Indian stone sculpture attend bejewelled princes. There is a sense of timelessness and calm. Nowhere more so perhaps than in the fabulous series of portraits of Sultan Ibrahim painted by the two star artists of his atelier, Farrukh Husain and Ali Reza.

The same sensuous spirit animates Bijapuri architecture, where fantastical outsized domes swell out of all proportion to the structure that supports them, bursting swollen from their drums as if about to break open into flower, and where the arabesque stucco work swirls with a restless, almost organic energy. Nowhere is this more true than in the tomb of Sultan Ibrahim himself, completed in 1626, one of the greatest—and most charming—of all India's monuments.

I went to the mausoleum my first morning in Bijapur as a young backpacker, 30 years ago. The tomb—an exquisite jewel box of a building—lies within a low-walled enclosure just beyond the black bastions of the Adil Shahi walls. Behind it lies open farmland, rich, well-watered black earth where bullocks plough fields edged in palm groves and mango and guava orchards.

Out of the pastoral landscape rises the great double domes of Ibrahim's mausoleum. From afar it looks uncompromisingly Islamic. Yet, for all its domes and arches, the closer you draw the more you realise that few Muslim buildings are so Hindu in their spirit. The usually grim and austere walls of Islamic architecture in the Deccan here give way to a petrified scrollwork indistinguishable from Hindu decoration, as the bleak black volcanic granite of Bijapur is manipulated as if it were as soft as plaster, as delicate as a lace ruff. All around minars suddenly bud into bloom, walls dissolve into bundles of pillars; fantastically sculptural lotus-bud domes and cupola drums are almost suffocated by great starbursts of arabesque which curl down from the pendentives like pepper vines, winding their way up brackets and gripping around the cusps of archways. This tomb is no necropolis, not a place of mourning so much as an aesthete's pleasure garden, alive with fine architecture and playing fountains, a resort outside the city to smoke a hookah with the ladies of the court.

Ibrahim's audiences typically took place in such pleasure gardens in the cool of night, attended by more than 500 bejewelled women, who danced and played instruments while the Sultan deliberated. In the wide-eyed letter that Cornelis wrote to the Dutch East India Company after seeing his first court durbar, he told of how during their first audience, Ibrahim asked him 'to make something'. A fortnight later, the Dutchman was granted a second audience so that he could present a three-by-two-foot Mannerist painting of Venus, Bacchus and Cupid.

Ibrahim was mesmerised. 'The King approved of it, and held it for two hours before his face, while I talked. He asked me if I wanted to serve him for a time, promising to give me great riches. When I swore him service, he showed me great honour, and further gave me a purse with 500 Pagodas of money. He ordered me to make another work…which now with God's help is going even better.'

In time, in addition to the 500 gold pagodas—an enormous sum—he also gave Cornelis the title Nadir-uz-Zaman (the Most Excellent of the Age), made him 'the Third Counsel of the King' and presented him with a Bijapur mansion so magnificent that after his death, it was considered to be a suitable residence for the Persian ambassador.

During the reign of Ibrahim, India was dominated by the powerful Mughal Empire, which from Agra ruled all of north India, as well as most of modern Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. But the south-central belt of the Indian peninsula—the Deccan—was fragmented into a patchwork of small but culturally dynamic sultanates, the most prominent of which was Bijapur.

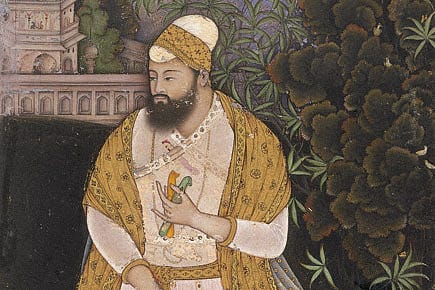

Sultan Ibrahim was the one-man catalyst for this outpouring of creativity. The Sultan was a contemporary of the greatest of Mughal emperors, Akbar, but while Akbar was an illiterate general and man of action, Ibrahim was a romantic and a dreamer. While Akbar liked to have himself depicted at the head of his army, storming Rajput forts, Ibrahim is typically depicted either sleeping, being fanned by his servants and having his feet massaged as he slipped into the reverie of his siesta, opium cup by his side; or else strumming his favourite lute. One portrait shows Ibrahim sharing an intimate moment with a lover. Another shows him clicking castanets: all perfectly appropriate ways of depicting a ruler who wrote that the two most beautiful things in the world were a lute and a beautiful woman.

My personal favourite of the many portraits of Ibrahim is by the Persian émigré artist Alireza, and it shows the Sultan of Bijapur wandering through the haze of an emerald forest in a fantastic landscape, lost in thought, his gentle gaze directed slightly downward. The image is otherworldly and indeed almost psychedelic, the radically surreal and perspective-free miniature the perfect visual counterpart to the mystical experiments taking place in Ibrahim's court.

The artists, writers and craftsmen who worked for Ibrahim and who produced these portraits were drawn from a wide variety of different backgrounds and religions, and crossed the divide both between Sunni and Shia and Hindu and Muslim. For Ibrahim did share one very important quality with his Mughal contemporary Akbar: his fondness for and interest in Hinduism. Early in his reign, Ibrahim gave up wearing jewels and adopted instead the rudraksha rosary of the Hindu sadhu. He visited both Shaivite temples and the monasteries of the Nath yogis, and knew Sanskrit better than Persian. According to the art historian Mark Zebrowski, 'It is hard to label him either a Muslim or a Hindu; rather he had an aesthete's admiration for the beauty of both cultures.'

In his book of songs and poems, called the Kitab-i-Nauras, Ibrahim uses highly Sanskritised language to shower equal praise upon Sarasvati, Hindu Goddess of learning, the Prophet Muhammed and the Sufi saint Gesudaraz of Gulbarga. In the 56th song, this Muslim Sultan more or less describes himself as a Hindu god: 'He is robed in saffron coloured dress, his teeth are black, the nails are red… and he loves all. Ibrahim whose father is God Ganesh, whose mother is Sarasvati, has a rosary of crystal round his neck… and an elephant as his vehicle.' Ibrahim's preferred Sanskrit title was Jagatguru, 'World Teacher'.

Bringing together Hindu and Muslim in an atmosphere of heterodox learning, and uniting Persians, Africans and Europeans in a cosmopolitan artistic meritocracy, Ibrahim presided over a freethinking court in which art was a defining passion. Through music and art, he believed that his people could learn to look at each other with mutual understanding:

'They speak different languages, he wrote,

But they feel the same thing:

The Turk and the Brahmin.'

Mark Zebrowski, who laid the foundations for the study of the art of Bijapur with his 1983 volume, Deccani Art, argued persuasively that Bijapur's mix of Persian and south Indian influences produced art unlike that found anywhere else. 'Whereas Mughal painting clearly illuminates the world through realistically observed detail,' he wrote, 'Deccani painting presents us with a civilisation seen through the charmed mirror of poetry… Whereas Mughal art has a generous dose of logic behind its glamour, Deccani art revels in dream and fantasy. Paintings pulsate with restless lines and riotous colours… Portraits of Ibrahim aim to establish a gently lyrical atmosphere, often one of quiet abandon to the joys of love, music, poetry or just the perfume of a flower. Moods are established through fantastic colours. Reflection and reverie triumph over dramatic action.'

There is, however, about the art of Bijapur something so dreamy and refined that it often feels somehow too rarefied to survive the real world. A kingdom so obsessed with the arts could only be hopelessly vulnerable to more worldly and militaristic forces.

This is not just a modern perception. Jacques de Coutre, a Flemish jewel merchant from Bruges who visited Bijapur five times between 1604 and 1619, saw the ageing Ibrahim in a different light to the generous patron described by Cornelis. For De Coutre, Ibrahim was instead the weak pacifist who paid off the Mughals to avoid war. He quotes Ibrahim as saying, "Why would I want to make war on the Great Mughal? I would rather offer him money as a gift, and keep him content, and be his friend, and remain in my house in peace and quiet."

Ibrahim continued throughout his reign to ply the Mughals with presents, sending embassy after embassy with precious jewels to keep them at bay: one scholar has even suggested that the absence of jewels in portraits of Ibrahim might be to prevent the Mughals asking for them as presents. In their wake there followed Ibrahim's daughter, sent as a bride for Akbar's son Daniyal, as well as one of his favourite elephants, Chanchal, sent, writes de Coutre, 'in order not to make war and put [himself] at risk of losing his lands.' The pressure of having to appease the ever-growing ambitions of the Mughals eventually turned Ibrahim into a paranoid recluse: 'When he reached old age,' wrote De Coutre, 'he did not have any more with which to make war, even if he had so wished, and he succumbed to the thousand requests the Mughal asked of him.'

To keep the Great Mughal at bay, Ibrahim supported him in a war on the rival Deccani sultanate of Ahmadnagar, led by the former African slave, Malik Ambar, one of the great guerilla commanders of his day. Inevitably, the war went badly, and in 1624 Malik Ambar swept through the sultanate's defences and burnt Ibrahim's newly built suburb, Nauraspur. Ibrahim died three years later, demoralised and depressed.

It was the puritanical Emperor Aurangzeb, appalled by Bijapur's reputation for liberal freethinking, who marched on the city and besieged it in 1685. The city held out for 18 months, before Ibrahim's great grandson finally handed over the keys in 1686. The city was looted, and left the backwater it is today.

But for the extraordinary miniatures with their fabulous chromatic experiments which were preserved in the libraries of Rajput princes who looted the Bijapur palaces as part of the conquering Mughal armies, no one would ever know the existence of this remarkable but until recently completely forgotten moment in Indian art history.

(Next week: court painter Nainsukh and Pahari art of the 18th century)