Kamal Haasan: A Star in Search of a Bigger Sky

AS AN EMERGING STAR, there were two things Kamal Haasan knew he had to get behind: being short and being a school dropout. A whipsmart actor roaming the theme park of the Tamil imagination, his delivery was convincing and his characters memorable. Like the rasping waves that thrashed his home town in Ramanathapuram, his low guttural voice seemed to command awe, respect, even dread. Stature was his if he wanted it. He would grow tall enough to play a dwarf in Apoorva Sagodharargal (1989)—a role that became a milestone in his career, the first of many that would use body language and make-up to elevate a character. Directed by Singeetham Srinivasa Rao, it became the highest grossing Tamil film of all time, until its collections were broken by Baashha, the 1995 cult superhit starring Rajinikanth.

The second flaw rankled. The high school dropout had to prove to the world that he was a thinking man; his head was abuzz with large questions that he had been seeking answers for in Gandhian and Periyarist literature, in Stephen Hawking and Edward de Bono, in the Srimad Bhagavatam and the Qur'an. An afternoon spent waiting for him in the conference room of the Makkal Needhi Maiam party office on Eldams Road in Alwarpet, Chennai, yields ample evidence of a life lived along the twin rails of thought and creation. The Padma Shri from 1990 signed by the then President R Venkataraman hangs on a side wall. Behind the glass panes of a bookshelf, a golden statuette is wedged against works on music, cinema, art and philosophy. The library appears carefully but artlessly tended, much like his image of late—that of a global intellectual with a wry tenderness for the Tamil motherland and a desire to delve into real issues. Echoes of his socio-political outlook, formed in the condenseries of such reading rooms, resound through Vishwaroopam 2, the circumquel that is up for release on August 10th after five long years in production and delays.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The PR team, busy carpet-bombing the media with promotional material on the spy thriller, has been extra-gracious with interview requests and Haasan has run out of time at the end of a day packed with over a dozen meetings. I ride with him in a white BMW to a glitzy venue nearby where he has to make an appearance after swapping ripped jeans and waistcoat for dark eveningwear. He prefers to sit on the left, leaning back against a pillow, and listens intently. There are no deities hovering over the dashboard, no divine symbols to ward off the evil eye. The irony of being hailed as 'Alwarpet andavar' (God of Alwarpet) is not lost on him. "It is a limiting epithet," he says, laughing. "Andavar is my fans' rib against me for being a non- believer." When it came to picking a name for his secular political avatar, however, the title just wouldn't do. "Ananthu (filmmaker K Balachander's assistant) had picked the name Nammavar (literally, one of ours) for a film we made in 1994. I thought we could go with it," he says. In the film, Haasan plays an irreverent professor of history who redeems a college from an unscrupulous administration.

Scruples. Kamal Haasan's politics is hinged on them. It is built upon the ruins of Dravidianism, whose last great generals have left behind a fractious and uncertain legacy that has strayed far from the original ideology of CN Annadurai. After a lot of back and forth, when 63-year-old Kamal Haasan took the plunge at a mega event in Madurai in February 2018 by launching Makkal Needhi Maiam (roughly translating to Centre for People's Justice), sharing the stage with Tamil Nadu's newest chief ministerial aspirant was Delhi's own activist-Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal. Like Kejriwal's, Haasan's cri de coeur stressed on accountability, clean governance and people's participation, betraying a naiveté that his critics in Tamil Nadu find absurd. "Some people didn't like it when I said, 'Thieves have turned you into beggars.' They ask me, 'What will you give us?' and all I can say is 'I give you my services and nothing more, and you must keep a check on me—don't just vote and forget'," Haasan says. When Kamal Haasan talks politics, his eyes betray some of the rawness of Rangan, the angry unemployed youth in Varumaiyin Niram Sigappu (1980) who would take no shortcuts to success. "Politics is not about instant revenge. I am in it for the long haul," he says. "The Dravidian legacy cannot be owned by two or three families. But, the revenge for having been a slave is only freedom, not enslaving the master. Very few people understand this."

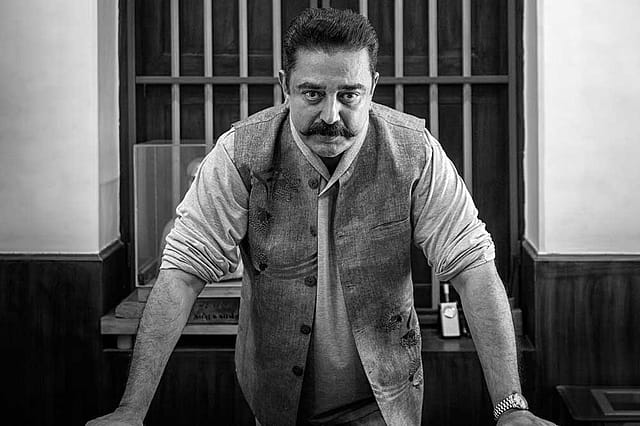

FOR SOMEONE WHO has spent his entire life trying on different personalities, Kamal Haasan is working harder than ever to slip into his newest role. Not since the 1970s, when he was wrapping up a film every three months, has he worked this hard. "I lived in the studios, but I did it for very selfish reasons. I was paid money to do it. I wouldn't push myself to the limit if I was paid crores today. Politics is like mountaineering. You are frustrated after sitting in an office all day and then you decide to go on a 14-hour hike. It's the most rewarding experience." Wikipedia now describes him, first and foremost, as an Indian politician. When did he cross the rubicon? "The bridge was already there. I was at the wrong end playing Horatio. I thought that was no way to lead a life. I was thinking politically even 20 years ago, but when you are not sure, you continue doing what you do best, so I made Hey Ram instead," says Haasan, filmdom's original moustache muse, twirling the thicket on his face. "I am ready now. I still have a few business commitments (Sabaash Naidu/ Shabaash Kundu is in the final stages of shooting, and he intends to make a sequel to Indian), but when I go into election mode, I cannot be fooling around. Films won't just take a backseat, there can be no seat but this one," he says.

"Kamal Haasan can hold forth on just about anything. He is like Google, but would you vote for Google? The reason he is still riding two horses is that he knows he may not have a bright political future," says Maalan Narayanan, a senior journalist from Chennai and former editor of Dinamani and Kumudam. "Unlike Rajinikanth, who cultivated a pro-poor crusader image onscreen, Kamal Haasan will find it hard to channel his cinema for his politics. The Hindi teaser for his new film, for instance, has a message about being a good Indian rather than a good Muslim, but these drawing room platitudes won't work in Tamil Nadu. The upcoming General Election will be all about arithmetic, not ideology, not even about larger-than-life leaders," Narayanan says.

An opinion poll conducted by Thanthi TV last month suggests that the DMK- Congress coalition may walk away with 41 per cent votes in the Lok Sabha elections next year, the AIADMK with 25 per cent, and TTV Dhinakaran's AMMK with 8 per cent. Kamal Haasan's Makkal Needhi Maiam and Rajinikanth, should he launch a party in time, are pegged to bag 5 per cent each, only marginally better than the PMK at 4 per cent, the BJP and Naam Tamilar at 3 per cent each. Haasan's Maiam is expected to eat into the urban AIADMK vote and Rajinikanth into the ruling party's rural vote. The BJP may prefer a multi-cornered contest in Tamil Nadu, with Haasan walking off with a small chunk of the anti-saffron vote.

TO KNOCK A bigger dent in the runaway train that is Tamil politics today, Kamal Haasan has to make a Jedi move, and he has to do it fast. He has pitched himself as a centrist—inspired, he says, by Buddhist and Advaita philosophy— built from the parts of unconnected political ideologies. He may have disarmed himself by not picking a side, but even Tamil writers and leaders who admire the artist in him say they find him lacking in political maturity. "Even if he joins a coalition, he would not be projected as its chief minister candidate, so the first election will likely be a dry run for him," says D Ravikumar, an anti-caste activist, writer and Viduthalai Siruthaigal Katchi leader. "His is an artist's fickle mind—what makes him a versatile actor could also make for erratic politics." On the one hand, Kamal Haasan seems to harbour an almost perverse grievance against his community, perhaps in an effort to snag anti-Brahmin votes, but at the same time, he is sharply critical of the Dravidian pabulum that has been fed to the masses. "He has made some very immature statements. Asking students to not fill the caste and religion columns in their school admission certificates reeks of upper-class privilege—he does not understand how important this identity is for the underprivileged," says writer Charu Nivedita. "He will struggle to find acceptance among both forward and backward communities."

As a radical filmmaker and actor, he shook south Indian society out of its comforting falsehoods with the feminist masterpiece Aval Appadithaan (1978), the searing black comedy of Pushpaka Vimana (1987), and the loaded politics of Hey Ram (2000). His words as a politician, couched in clever puns and poesy, don't have the bite of a Prakash Raj's or a TM Krishna's, and he sometimes slips into an oracular ambiguity when questioned about his manifesto. "I have no doubt he means well. He is certainly not manipulative like Rajinikanth," says writer and film historian Theodore Baskaran, who likes Haasan for his sincerity. "For a star, there comes a point when he realises that the power he wields over his audience is illusory and he wants to convert the illusion of popularity into reality. This is why stars take to politics," he says. Haasan's socio- political outlook has matured over the years, says Baskaran. "As a young man, he was a regular at international film screenings in Chennai. He also understands the difference between theatre and cinema— which Sivaji, Karunanidhi and Annadurai never did. When he gained control over his films, he favoured liberal secular scripts, often dealing with timely, urgent matters. Women won't be discounted in his films, for instance," Baskaran says.

HAASAN ADMITS THAT in the early years, he had to contend with working for "inferior filmmakers". "I had to seek out good films that were also commercially viable. People got angry that I gave priority to Balachander. I would leave everything and run to him. We worked on 36 films. All because there was a possibility to do good work. Balu Mahendra, who was a good friend, wasn't as prolific. He made a handful of films when he could have easily made another 40, and towards the end he felt regret. Other filmmakers like C Rudhraiah, who showed promise in the beginning, meandered and faded away. Yet others were not compatible with me. They were intimidated by my stardom," Haasan says. Does he enjoy scriptwriting? "I am one of the fastest writers in the country. But then I learned from people like KB who wrote even as the film was being shot, and Malayalam writer T Damodaran who could finish a script in 10 days."

In 2013, Vishwaroopam, Kamal Haasan's geopolitical magnum opus, partly set in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, suffered massive losses after district collectors, acting on the orders of the then Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa, asked theatre owners in Tamil Nadu not to screen it, citing law and order problems. Muslim organisations had expressed outrage at some scenes, which were eventually muted. Written, directed and produced by Kamal Haasan, the film finally released in the state weeks after its international release, but the damage was done. Haasan was consumed by indignation—"at a politician's high-handed interference"—and briefly considered leaving Tamil Nadu. He has since lent his voice to landmark protests that have strived to speak truth to power—against the ban on jallikattu; against the flagrant cruelty of the police in Thoothukudi that left 13 dead and over 120 injured; against the Salem-Chennai greenfield highway project. "The wave of protests sweeping Tamil Nadu has one common theme. We all are talking about the ascent of man, not the ascent of God. It has been a theme for the world's civilisations. Every time man goes to defend God, it ends up in war. When man upholds the spirit of community that all religions preach, he makes progress," he says.

Vishwaroopam 2, too, has been delayed due to financial issues between the original producer and Kamal Haasan. Haasan says he has never fought as hard for any project as he did for Vishwaroopam. Does he think the sequel will overtake the array of Rajinikanth films—Enthiran (2010), Kabali (2016), I (2017)—that fill the top grossers chart? "The numbers are debatable," he says. "When you are dealing with the black money economy and politicians laundering money through cinema, what is the right number and what is the wrong one? What I can say with confidence is that Vishwaroopam 2 is no mean technical feat. Some of my colleagues, both admirers and detractors, will have to accept that it is not an imitable act."

Does he self-censor his films now to avoid skirmishes not only with the Central Board of Film Certification, but also with communities that seem to take offence at the most innocuous mention? "As a commercial filmmaker—and now as a politician—I have to be inclusive. I want everyone to watch my films. It was a proud moment for me when Gopal Godse (co-conspirator in the plot to assassinate Gandhi) sent a congratulatory message after watching Hey Ram. Apparently he clapped at the theatre," Haasan says. "If people can set aside ideological differences and start a dialogue, it's a success for art—and for politics."

Outreach could be a problem for an incipient politician, but Haasan says he has that part figured out. Apart from an app, membership drives, roadshows and social media engagement, he says films and Tamil Bigg Boss have become a valuable stage for political messaging. "Look at the logistics of arranging a public meeting. Assembly of people, even on a beach, costs money. That's happening on Bigg Boss with minimal effort. No politician can match this. They can bring 5-6 lakh people together, logistics permitting. But Bigg Boss could be playing on your TV even if there is Section 144 in the state. It's a large audience and I get to deliver messages to them in capsules. I am not going to make them memorise my manifesto, but this is enough. They look into my eye. This is direct interaction and social media is no match for it."

Other than MG Ramachandran, no actor in the history of Tamil Nadu politics has commanded a following large enough to ensure political success. Jayalalithaa, it must be noted, did not take the cinematic route to politics—she gained entry into the AIADMK because of her proximity to MGR. But while MGR, when he transitioned into politics, had a politically homogenous mass of fans, namely DMK supporters, Sivaji, whose shortlived Tamizhaga Munnetra Munnani (TMM) lost every seat that it contested in the 1989 elections, could not manage to convert fandom into votebank. Haasan appears undeterred by the number of actor-politicians who have fallen by the wayside over the years. "I am here to challenge the status quo," says Kamal Haasan, with the studied confidence of an overachiever. "I like all the three colours in my flag. I don't want one seeping into the other," he says. Beneath the wordsmithery, the self-mythologising and the highbrow cultural references—Cesare Borgia and Gramsci among them in the course of a half-hour drive to the airport—is a star who sincerely believes that if he shines brightly enough, he might just be able to rearrange the constellation in the sky.