House Warming

AT 40, I OWN A HOUSE. This is not a boast. Rather a confession. My husband and I don't inhabit it yet, but all my life, I've lived only in rented accommodation and so this seems like an aberration. Something unknown, unexpected. One doesn't get to only decide the colour of the curtains or the paintings on the wall, but suddenly one has a say in the tiles of the kitchen, the patterns on the floor and even the number of windows in the walls. While I've been playing down this new possession, a friend rightly reminded me that all these years I'd resisted even buying a couch. And it hit me then, I've always chosen diwan over couch. Compact over cumbersome. Everything needed to be compressed—tablet-like TV, toadstool-like fridge. I am not cool enough to contain all my possessions in four suitcases. I am, sadly, no minimalist. But I've always imagined my home to be a carapace. Something portable on the back. Something mobile. Something unrooted. And, most importantly, something light. And owning a house seems quite the opposite. Renting a house is like being a tortoise with its shell. The shell just comes along with you. Owning a house is like being a cat, you walk in, mark your boundaries and then never stray too far.

The owning of a house is laying claim to territory. And it is something that authors have long thought about. What is the effect of owning property? What does it do to you? Does it make you feel heavy? Or does it make you feel light? Lionel Shriver has an entire collection of short stories titled, Property, which deals with how our houses can either liberate or shackle us. In her three living autobiographies, Deborah Levy has been occupied with ideas of home. In Real Estate, she writes that at the age of 60, she moves to Paris on a fellowship and moves into a sparsely furnished rental. Working in Paris, and with her daughters having flown the nest, Levy imagines the "major house" of her dreams, but knows that she cannot afford it. 'Real' means 'king' in Spanish (and 'royal' in Latin), she writes, 'real estate' has roots in the fact the kings used to own all the land in their kingdoms. The ownership of land was always something for kings and not commoners.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In real estate hierarchy, renting is always inferior to owning. Delhi has grown me. And anyone who has rented in Delhi (or in any big city for that matter), knows that as a renter is to be at the mercy of the owners. You've to first contend with broker. Then landlord, who will look at you questionably if you are single. He will raise both eyebrows and objections when you say you are a journalist. If you are ridiculously lucky, you will get the house, and it wouldn't have pink walls, and it will have running hot water. Then you'll have to manoeuvre your way around the landlord's dog, chained to the entry gate. Which will invariably be a maniacal Pomeranian. Named Lucky. Or Rocky. That takes the stairs only to poop on your doormat. It will be a house where a drunk young man will wander up the stairs and loiter on the terrace, only because he's seen girls on the balcony, and feels he has a right to intrude into the space, to inspect what is going on. You'll then have to figure out escape routes—not for the drunk lout—to avoid the landlady who has requested if her son can come and study in your home, since her house is too noisy. You don't know how to tell her that since she's rented the barsati to you, her son cannot use it. Instead, you try to slink in and out of the house at odd hours. You'll also have to battle rats. And not Ratatouille's Remy the Mouse. But Brontosaurus-like rats. Which wakes you up at night by chewing through cement. And then insist on dropping dead in your bathroom (because of the poison you left out). As you lift its heavy corpse out in a dustpan you wonder if it is easier to deal with an alive or a dead rat. You've never dealt with a dead-anything. Other than perhaps, a cockroach or a mosquito. So, you toss it out from your balcony. Given your weak throw it promptly lands in the landlord's house. Right near Lucky. Or Rocky. For a second you wonder if Lucky or Rocky should just eat it. But then your Humanity kicks in and you yell to the landlord, "Uncle mai terrace pe khadi hu, maine neche chua dekha. Lucky kha jayega. (Uncle, I'm standing on the terrace and can see a dead rat below. Lucky will eat it.)" The Uncle will reply, "Arey beta, mere ghar mein bahut chuhe hai. (Oh, don't worry, there are many rats at our home.)"

Anyone who has rented in Delhi, as a student or a young professional, will have a version of the above story. But I also had a very different story. I stayed in the same home in Delhi for nine years. I was the chief flatmate, who'd rent out the second room to a series of flatmates. Six to be precise. Like so many Delhi houses, the landlords lived downstairs. We didn't spend hours drinking chai or discussing politics. But for me that house in Sarvodaya Enclave, and their presence downstairs was the ground beneath my feet, for close to a decade. Husband and wife had worked in government banks. Both were retired now. Their only outings were to the temple. Their only friends seemed to be the neighbours. On every festival (and in their calendar there were numerous occasions) they'd ring my doorbell and hand me a plate of puri, aloo, channa, raita, salad and kheer. They adhered to the Landlord CCTV routine, which entailed peeping through the bedroom curtain every time they heard the gate open or shut, at all times of night and day. Every Diwali we'd exchange elaborate gifts. My routine, or that of my flatmates, differed vastly from that of their young working son and daughter-in-law who lived with them. But these differences were accepted, and no one was questioned about it.

From the start, I adored the house. In the early years, when the end of the lease was nearing, I'd be paranoid that they'd ask me to leave. But by year four, or was it five, I no longer felt like a renter. My existence did not feel precarious, dependent on the whims of a landlord who might hike the rent or even demand the house back. It was roomy and sun-filled, with a balcony in the front and back. It boiled in summer and froze in winter. But it is the place I stayed longest at. It felt like a shell on my back. I left on my own accord.

My parents lived in 17 houses in 35 years of government service. The houses varied from the scenic (mountain facing) to the despairing (mosquito filled pit for commode) to the spacious (a bungalow). Looking back, I marvel at the seeming alacrity with which they packed up, relocated, unpacked and settled. They brightened and beautified the bleakest of quarters. For my sister and I, 'home' was never a pin code or a neighbourhood. It was the paintings on the wall, the plates on the dining table, the books on the shelves. For many people, all of this is just 'stuff'. But when relocation is a way of life, this 'stuff' is the sum and substance of home. To my parent's credit, they left every house in a better condition than they found it, allowing in light and laughter. House hunting is never a joyful task. As Shriver reminds one in her story, 'Vermin,' when you step into an apartment you can immediately pick up that the previous residents had been unhappy there. One can only hope that prospective tenants walked into 17 houses and felt a sunlit vibe.

Owning a house has the advantage of stability and constancy. It is yours and yours for good. You never need to worry about landlords again, now that you are the landlord. It is also an enormous responsibility. Suddenly you are no longer just factoring in the rent for the coming months. Instead, you are thinking of EMIs for the next decade. You can no longer stay removed from neighbourhood WhatsApp groups. You now have to witness the pettiness of neighbours who raise a furore over a dog not on a leash or a lazily parked car. Also, suddenly there is no Uncleji to call over a bust geyser or an empty water tank. In the short story 'Possession' by Lionel Shriver, a woman proudly starts refurbishing a house she has bought. But on day two she finds that she is unable to open the main door. In that second, she realises there is no landlord to call. She is a homeowner and on her own. With owning a house, the buck stops firmly at one's own doorstep.

Wanting a house, owning a house, it can do strange things to people. The story, 'My House' by George Saunders deftly illustrates what owning, buying and selling a house can do to one's psyche. Every family knows how easily property can cause discord. It can shatter relationships and enervate trust. It can make monsters of, otherwise, decent humans. Saunders' story from the collection Liberation Day, illustrates how instead of possessing a house, a house can possess you. Mel Hays has a gem of a house that he wishes to sell as he cannot maintain it and has a sick wife to attend to. The narrator, the prospective buyer, and Hays hit it off immediately. They like the same things about the crumbling manor, which is rich in history and memories. By the end of the meeting, the narrator is convinced that the house is going to be his. Just as he is about to leave, Hays asks if he can, perhaps, drop in, or even stay for a day or two. The narrator pauses before accepting. And in that moment of pause, the surety of their agreement and relationship falters. The seller bails. The prospective buyer is left confounded. Unable to accept the rejection, he starts writing vicious letters, which border on the unhinged. It is a story of just a few pages, but captures how the buying and selling of houses can warp the mind. Something we've all, perhaps, seen in our own lives.

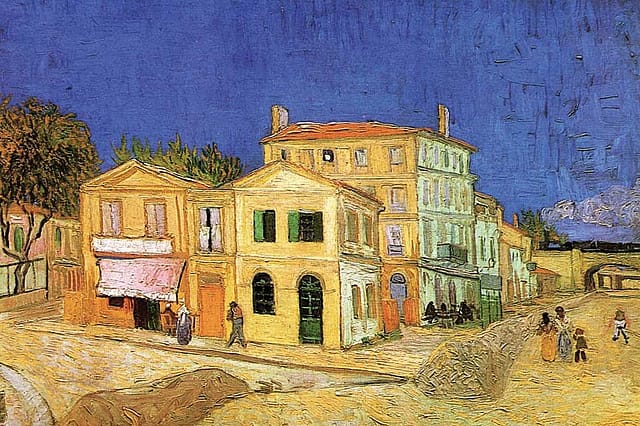

The owning of a house is the ultimate embodiment of self. As Levy writes with such eloquence, "If real estate is a self-portrait and a class portrait, it is also a body arranging its limbs to seduce." Our home is an expression of the self and a marker of how society will see us and our family, and where society will place us. Everyone has a vision of what those four walls will look like. For Vincent Van Gogh it was a yellow house with green shutters in the south of France. A place where he could work, and invite like-minded artists to come paint. Levy comes to the philosophical conclusion that in the final reckoning her books are her real estate and the only physical thing she actually wishes to own. Levy's interest is always in how to feel "like herself". Her books are her home. The pull of home is, after all, the certainty that one can sense the sky while being within walls.