The road to prosperity in India is being paved by the nation’s large and growing middle-class population. By 2047, if political and economic reforms have their desired effect, India is expected to become the fastest growing economy in the world. Over the next 25-year period, at a sustained and conservative annual growth rate of 6-7 per cent, average annual household incomes are set to rise to about ₹20 lakh ($27,000) at 2020-21 prices. The population count would have risen to more than 1.66 billion when the nation celebrates its centenary year of independence. By then the middle class would be poised to become not only the biggest income group in the country in numerical terms but the major driver of economic, political and social growth.

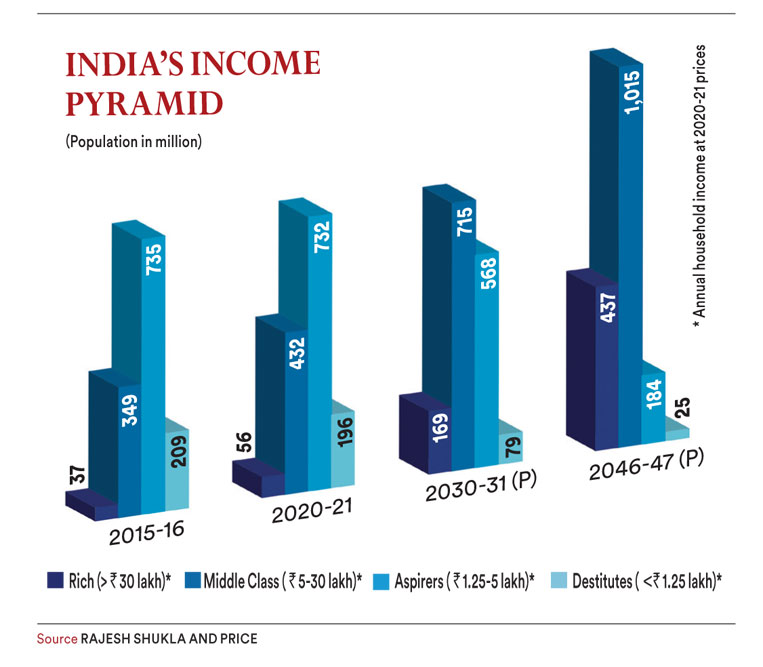

Today, one out of every three Indians belongs to the middle class, making it a dynamic group of 432 million people. Expanding at the rate of 6.33 per cent per year, the middle class comprises of households with annual incomes ranging from ₹5 lakh to ₹₹ 30 lakh at 2020-21 prices. It represents 31 per cent of the population currently, is expected to form 47 per cent of the population by 2031 and 61 per cent by 2047.

This middle class has helped drive India’s enviable record of economic growth over the last 30 years. A large middle class (as opposed to a few rich and a sizeable segment of poor) leads to higher domestic consumption because it has a higher marginal propensity to consume than the rich and is financially secure compared to the poor.

The middle class is also more likely to have acquired certain assets and is in a position to take more risks, thereby becoming a source of entrepreneurship and job creation. Moreover, it supports growth by strengthening social cohesion and enhancing political stability. The process of growing the middle class also supports economic growth because human capital investments are key to acquiring the skills required to obtain middle-class jobs, and also to accelerating growth.

A rapidly growing middle class is good for its members and good for India’s economy for the following main interrelated reasons.

Household luxuries like air conditioners and water purifiers are non-existent below the middle class, while car ownership in particular divides the middle class and rich from all other Indian households

Share this on

First, a growing middle class indicates higher disposable incomes and better standards of living. Second, higher incomes fuel consumption growth that drives the economy. Besides it also translates into growing the base for income tax revenues that can then fund public investments, governance, risk mitigation and poverty reduction programmes. Third, a rapidly growing middle class is closely linked with reducing inequality as more and more people belonging to the underprivileged sections aspire to join in. Fourth, there is also the risk that if the middle class fails to expand and include those who aspire to join it, or if policy interventions are aimed at benefiting only the middle class, it could lead to a more polarised and fractious society. Finally, increasing labour productivity and mitigating the effects of an ageing population need special attention.

Middle-class consumption has grown at 9.8 per cent annually since 2005 and now represents close to half of all consumption in India. By comparison, total average household consumption growth was only 7.4 per cent annually over the same period and 16.1 per cent for the rich. Even more significantly, the total poor household consumption actually declined by 1.4 per cent annually in real terms and grew at only 4.4 percent annually for the aspiring class. It is therefore imperative that the government maintain a strong focus on reducing poverty and vulnerability or else the middle-class story could go awry.

Increasingly, the middle class is spending its disposable income on non-food items, such as education, transport, housing, communications, and other services. Indians spend a large proportion of their money on food. In fact, food represents 67 per cent of all consumption for the bottom-most income group (Destitute) and 63 per cent for the aspiring class (the group just below the middle class in terms of income). The middle and rich classes in contrast spend more on non-food items.

However, for most middle-class households, food comprises 51 per cent of consumption. Only for the top creamy layer of Indian society, the food component is less than half of total consumption. With greater affluence, the middle class is spending more on health and education—representing 16 per cent of its expenditure. Housing, travel and other services form nearly 18 per cent of middle-class spending.

As disposable incomes have grown, the middle class has become big consumers of entertainment and durables. Entertainment accounts for 5-6 per cent of total consumption. While essential durables, such as refrigerators, are being purchased by a large number of households, products that are oriented towards comfort and convenience—air conditioners, laptops, and air purifiers—are being bought by upper middle-class and rich households, especially in urban areas. Car ownership on the other hand marks a clear dividing line. While the middle and rich classes are most certainly car owners, the aspiring and poor households do not own cars.

More importantly, while the middle class formed just 31 per cent of the total Indian households in 2020-21 its share of total income is nearly half of the income and expenditure and it saves more than over a quarter of its income. The growing clout of the middle class becomes even more apparent when one looks at the ownership patterns of household goods. Nearly 58 per cent of all cars are owned by the middle class, compared to just 23 per cent by the rich. Similarly, 49 per cent of all air conditioners are owned by middle-class homes.

It is only as a household becomes middle-class that it begins to purchase products geared towards convenience and comfort. Access to computers and the internet are uncommon outside the middle class; thus middle-class children are far more likely to gain exposure to ICT that underpins the modern global economy.

The challenge now for Indians is to make growth more inclusive by providing economic mobility and growing the middle class. The pandemic has played a major spoilsport and has led to a dramatic rise in inequality, especially among those aspiring to join the middle class. High levels of inequality could have significant consequences not just in terms of economic growth but also with regard to social and political stability. Recent research indicates that high inequality leads to lower and unstable economic growth. Social costs of high inequality have the potential of derailing the middle-class story. For instance, when people perceive that a small section of people are becoming richer at the expense of the majority, it can cause social tensions and become a source of conflict. Regions with higher levels of inequality than the average in India have a higher rate of conflict compared with regions with lower levels of inequality.

Another key challenge for India is the growth in the country’s ageing population. Combined with the upcoming drop in the size of its workforce and sharp increases in public spending on welfare schemes, such as pensions, healthcare, and geriatric care in the coming decades, this will pose a challenge to sustained economic growth.

To become a high-income country and accelerate its growth rate—or maintain a sustained rate of growth—India will need to develop a more inclusive growth model. One that enables its people to both contribute to and benefit from. In the current scenario, despite declining poverty, many Indians (almost one-fifth who are in the category of Destitute) continue to remain vulnerable, and sustained attention is required to lift them out of subsistence and provide them with greater opportunities. However, action is also required for a further 52 per cent of the population—732 million people—who, while free from poverty, have yet to achieve the economic security and lifestyle of the middle class. To help these millions aspiring to join the middle class, India needs to create more jobs with better pay, backed by a robust system to provide quality education and universal health coverage. This will require improving the business environment and investing in infrastructure. It will also require expanding access to social insurance to protect against health and employment shocks that erode economic gains and prospects for upward mobility for millions aspiring to join the middle class.

The key to India’s closing the gap with high-income countries is a growth strategy based on improving labour productivity. To achieve this, in addition to improving the functioning of product, labour, land, and capital markets, significant investment is required to close the infrastructure gap (roads, ports, electricity, water and sanitation, and irrigation networks) and the skills gap (which requires improving access to key public services for young children and improving the quality and relevance of education for older children).

Today, the bulk of the tax burden is borne by the middle and rich classes. A new social contract is needed to grow tax collections. India’s government revenues are lower than many other middle-income countries. Thus, increased income-tax revenues would significantly increase available funding for investment in infrastructure and skills. Strengthening tax policies and administration to increase compliance by those already in the middle class and broadening the tax base to boost new collections from an expanding middle class will be required to finance these needed investments.

The middle class and its dynamism will be vital to India’s future as it stands at a crossroad. The growth of the middle class requires reforms and political stability to improve the business environment to create good jobs, invest in essential skills, and create a social security system that protects against shocks. Having the right policies in place to expand the size of the middle class can unlock India’s growth potential and will be able to boost the country to a higher income status.

About The Author

Rajesh Shukla is managing director and CEO, People Research on India’s Consumer Economy (PRICE)

More Columns

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha

Mumbai’s Glazed Memories Shaikh Ayaz