Elephant as a soldier, status symbol and myth

Aritra Ghosh examines the stature of the largest land animal in war and royal courts of ancient India

Aritra Ghosh

Aritra Ghosh

Aritra Ghosh

|

12 Aug, 2023

Aritra Ghosh

|

12 Aug, 2023

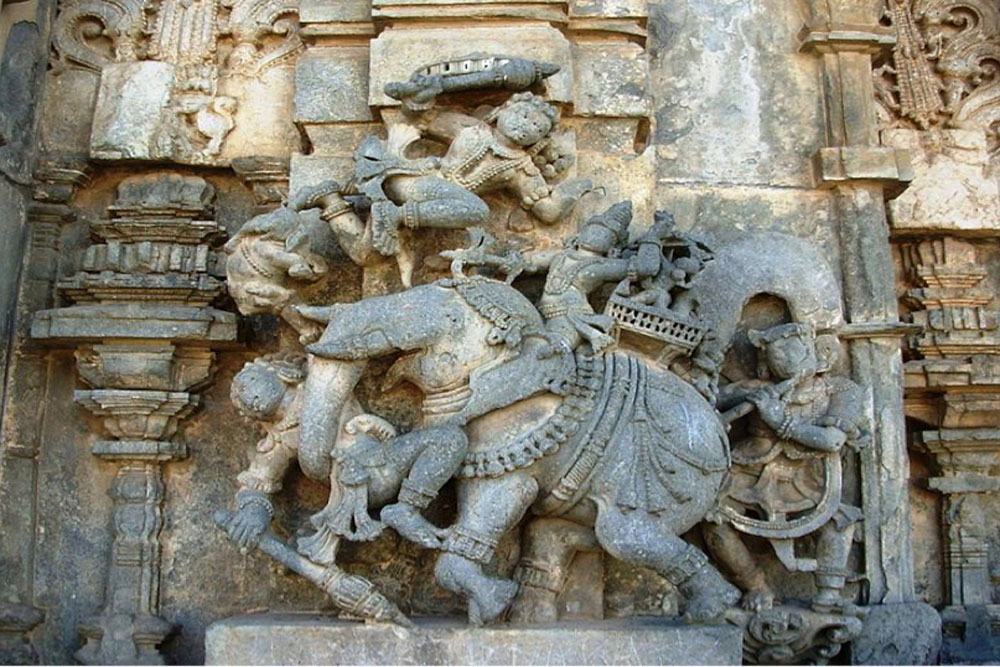

/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Elephant1.jpg)

A scene from the Chaddanta-jataka, Cave 17, Ajanta (Courtesy: Pinterest)

The figure of the elephant looms large in the history of premodern India. A plethora of historical sources demonstrate the involvement of the great creature with the affairs of the royal court. The Arthashastra generally attributed to Kautilya, for instance, advises the king to make use of the elephant variously as a hunting companion, in the construction of defensive structures like moats and ramparts, as an object of amusement, and so forth (respectively, AS 2.2.3, 2.3.5 and 2.32.16). The treatise also instructs the “would-be conqueror” (vijigishu) to establish and maintain elephant preserves in suitable zones at the frontiers of political organisation from whence domesticated elephants could be sourced for state use (AS 2.2.6–16). So far it lists eight “elephant forests” (hastivanas) where the great beasts dwelt: the Prachya forest, located in a stretch between the north-east and the east; the Kalinga forest to the south-east; from the east to the west about the central portion of the subcontinent, the Chedikarusha, the Dasharna and the Angareya forests; the Saurashtra forest of the Kathiawar peninsula, and; the Panchanada forest of the Indus basin (Trautmann 1982, 65). It is the presence of the lumbering animal in the Gangetic region, however, which deserves especial – if not singular – attention for the simple reason that access to the elephant contributed fundamentally towards the emergence and consolidation of cities and states in the region between the sixth century BCE and the early centuries CE.

The Advent of the War Elephant

Between the tenth and fifth centuries BCE, South Asia was the scene of an invention that would forever change the world of politics and kingship, and which would in time go on to have global ramifications of a remarkable character (Sukumar 2003, 55-75; Trautmann 2015). This invention was in the making of the war elephant as an institution. It is not certain how the idea to tame elephants specifically for purposes of warfare initially arose. In a scenario of emergent polities and frequent interstate conflict it makes sense that rulers would have actually sought to harness the unmatched strength of the elephant against their enemies as a matter of military strategy. It would not have taken long thereafter in adopting the elephant as an emblem of legitimacy and royal paramountcy. Their great strength and magnificence would have allowed for an easy association with the theory and ideology of kingship. Thus, not only are groups of elephants (hatthikaya) mentioned in the Pali literature with reference to the royal court as important resources for war, they figure as symbols of authority, dominance and status which comprise the jewels (ratanani) possessed by the universal monarch (cakkavatti) as well in the canon (Gokhale 1974, 111-12).

In texts belonging to the later Vedic corpus and in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, the elephant corps are depicted as the major regiment (anga) of the fourfold army (caturanga-bala), comprising also of the infantry, the cavalry and the chariot corps. The elephant is moreover put forth as the ideal mode of carriage for the king (raja–vahana; see AS 1.21.24). The motif of Indra sitting astride Airavata originated from the late Vedic corpus for example. Bhagadatta, the implacable king of Pragjyotisha who fought against the Pandavas from atop his cruel tusker Supratika, perhaps best represents this trope so far as the epics are concerned (Mbh 6.60). Further, in both poems, elephants are said to be set in motion as beasts of war through careful, opportunistic and systematic arraying (vyuha, see Ram 2.28.4, 2.80.8, 6.90.4 or Mbh 1.123.7 and 3.31.8 for instance). Their importance as resources for war and as icons of kingship is unparalleled in early literature. When Rama meets Bharata while in exile, he counsels his brother to tend to the elephant forests and look after the needs of the great animals (Ram 2.94.43). Even the Arthashastra includes time in the king’s busy routine for the survey and inspection of the elephants in the royal stable (AS 1.19.15). In the Mahabharata, in fact, is the idea explored that sometimes through something on the level of divine intervention alone can the power of a worthy elephant force – such as the one possessed by the ruler of Magadha – be broken (in that, Bhima is a powerful demigod and has the support of Krishna, Mbh 6.58.30).

In Early North India

The actual details about the political contours of North India around the time of the sixth century BCE may be inferred from the Pali canon. Lists in the literature refer to the sixteen mahajanapadas, i.e., Anga, Magadha, Kashi, Kosala, Vriji, Malla, Cedi, Vatsa, Kuru, Panchala, Matsya, Shurasena, Ashmaka, Avanti, Gandhara and Kamboja (see Janavasabha suttanta 1 of the Digha-nikaya; Anguttara-nikaya 3.70.17). The structure of this itinerary is such that one moves in order from the middle Ganga valley to the Indus basin, that is to say, from elephant country in Central and East India to horse country in the west and the northwest as one goes down the list. We know that Magadha is mentioned in the Mahabharata in association with the war elephant (Mbh 6.58.30). Yet, it is Anga which is stated as possessing a privileged association with the animal in the late Vedic corpus, and texts like Palakapya’s Gajashastra explain that king Romapada was the first to domesticate the elephant for use in battle (Gaj. 1.29–49). These posit moreover that the elephant science (gajashastra) meant to sustain in general and develop the elephant corps for war, was developed by the seer in the region of the same mahajanapada.

Nevertheless, Magadha emerged victorious when the two polities went to war about the fifth century BCE and added Anga’s resources and sizeable elephant reserves to its own. It is not surprising as such that the Haryanka king Ajatashatru was able to decimate the Videhan republic in the north with ease. In a conflict over the territory of Kashi with Kosala to the west however, Ajatashatru was ousted. The Pali canon credits the thera Dhanugahatissa for coming up with the solution of the wagon array as the only counter to the king’s robust military strategy in a conversation with his fellow monks, who were through a fortuitous turn of circumstance overheard by the courtiers of king Pasenadi of Kosala (see Vaddhakisukara–jataka 283). Kashi thus went to the latter. Later on, Kosala succeeded in taking over Malla as well. The Pali canon indicates that in time only the mahajanapadas Magadha, Kosala, Vatsa and Avanti survived to vie with each other for political supremacy.

After the Haryankas, the Nanda dynasty of ill repute ruled Magadha from their capital at Rajagriha and later Pataliputra for a period of a few couple of decades in the fourth century BCE. Their political programme so far as is divulged by the historical record was in conducting military conquests at a scale hitherto unprecedented. The objective was that of imperial expansion. We know this from the Puranic literature which identifies the dynasty as the scourge of the Kshatriyas (sarva–kshatrantaka) and from the Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela which makes mention of the military victories of the Nandas (Jayaswal and Banerji 1929-30, 71-89). The ancient Greek and Roman historians give a similar impression when they speak of a certain wariness on the part of Alexander’s army to venture beyond the Punjab region; this apprehension is attributed to the military might of the Nandas in their writings (see Arrian 5.26–27). The estimates given in the accounts of Diodorus, Curtius, Plutarch and Pliny as to the number of war elephants possessed by Dhana Nanda’s forces – 3000, 4000, 6000, 9000, respectively – appear to be exaggerated ones, but certainly confirm the idea that the elephant corps was an integral and conventional component of Magadha’s army (Diodorus 17.93; Curtius 9.2; Perrin 1914, 400; Pliny 6.22).

That elephants were given significant, perhaps even crucial, consideration in matters of war is borne out by two points. Firstly, the records of the Greek historians tell us that Alexander on observing and engaging with the pattern of warfare in South Asia felt the irrepressible need to incorporate the war elephant into his army about the time of his conquest in the region c. 327–24 BCE (Kosambi 1956, 180-188). This is noteworthy. The primary sources are very clear about the fact that cultivating the animal for war was an extremely difficult process. For instance, the Matangalila of Nilakantha exposits freely on the difficulties of domesticating the forest-dwelling elephant (ML 11.1–3). In poetic verse it speaks of the essential wildness of the elephant, of how though it may be subject to harsh words and cruel goads (ankusha) and cutting ropes, the elephant remains relentless in spirit. Moreover, that it endures despite bondage and all manners of sufferings of “mind and body” whilst longing in sorrow for the freedom of the wilderness. The treatise explains that even should the elephant give in out of weakness and fatigue to the machinations of its capturers – if, that is, it does not prefer to die first – it never still forgets the forest and desires to be free always. The general idea is that elephants cannot be fully domesticated; they remain wild by their fundamental nature even when they have been tamed.

Further, the Arthashastra and the Mahabharata both tell us of how only when elephants have reached late adulthood, i.e., when they are between four and six decades old, can they be the most successfully used in war (the former text advises the capture of elephants only above twenty years of age, AS 2.31.8–10; Mbh 4.14.20). Besides, it was preferred, the Mahabharata would have us believe, that the elephants were usually male and in musth or induced to the same during battle (Mbh 4.30.26–7). It would have required the organisation of exceptional manpower and strength, and clever use of the goad to restrain these overly aggressive and unpredictable giants to prevent them from going on a rampage. It must have been that much more difficult and dangerous to use them in war. Alexander was fortunate in that the Assakenoi beyond the Indus fled at his approach leaving behind their war elephants, so the Macedonian army was promptly able to take charge of the great beasts (Kosambi 1956, 182-184; Trautmann 2015, 192). The conqueror gained access to elephants thus as spoils of war. He also obtained them by means of gifts of friendship (the king of Taxila presented Alexander with 30 elephants, for example) and through the tributes sent in by local kings at the northwestern frontier upon their capitulation. Additionally, the latter category of rulers sent in specially trained elephant keepers and mahouts, who were responsible for tending to the elephants and preparing them for war.

Secondly, by the time we come to the Mauryas later on in the third century BCE, we observe that elephants had begun to be used as important resources for diplomacy. Seleucus, for instance, ceded his eastern satrapies to Chandragupta in return for five hundred elephants. This gives us to understand obviously the relevance of the elephant as a resource for political endeavour. Megasthenes’s Indica, a fragmentary but important source, speaks of the elephant and its uses in war (in Diodorus 2.36.1). It juxtaposes the figure of the Indian beast with that of the Libyan one and declares the former as being of greater size and strength. This we are able to confirm; the African Loxodonta cyclotis is indeed dwarfed by the Indian Elephas maximus on comparison. Furthermore, the Indica is of the opinion that the war elephant was singularly possessed of the capacity to turn the tide of battle and could therefore ensure victory. It is significant as such that it identifies the Mauryan army with respect to its efficiency in the suitable deployment of the animal during times of war (in Arrian’s Indica 12.2–4). Similarly, it is noteworthy that the sixth of the thirty-member Mauryan military committees was specifically responsible for looking after the general welfare of elephants under the charge of the superintendent of elephants (gajadhyaksha).

It is no wonder as such that elephants were given pride of place as fundamental symbols of political performance during the reign of the Mauryan empire. There was the elephant-head capital (hathinakhaka) which lent an air of grandeur to their architecture (Gokhale 1974, 114). There were also the intricate representations in stone of the white elephant motif at Dhauli and Girnar. Ashoka’s ability to deploy such value-laden symbols bespoke not only a privileged connection with Buddhism, but his capacity to draw upon the semantic vocabulary of the religious tradition to derive an exceptional degree of legitimacy as well. After the Buddha fulfilled the condition of the prophesy of his birth by becoming a mendicant, the white elephant could only ever have been the symbol of a cakkavatti so far as another was concerned. And though Ashoka does not especially mention them in his Major Rock Edict 13, it is certain that a good number of elephants perished in the bloody conquest of Kalinga.

In Early South India

So much for the war elephant in the north. During the period popularly known as the Sangam age (the third century BCE to the third century CE), the war elephant made an appearance in the southern part of the subcontinent as well. The literature of the Sangam corpus reveal references to kings in the South who made gifts of such luxurious items as muslin, silk, jewels, gold, horses and elephants to worthy subjects and temples. For one thing, the tropical forests in and around the vicinity of the Tamilakam were home to wild elephants from which elephants could be culled (Subrahmanian 1966, 292). The poetics of the Tolkappiyam formulate the geography of the South into five landscapes of distinct ecology: kurinchi (the mountain), mullai (the pasture), marutam (the cropland), neytal (the seashore) and palai (the wasteland). Each of these zones was marked by an aesthetic potential in correspondence with appropriate poetic circumstance (tinai).

It is the kurinchi which is of interest to us. The akam poems, which work essentially with the internal world of love, weave an idyllic picture of green mountainsides shrouded in mist where red flowers grew; there, the stillness and quiet were broken only by the chattering of monkeys, the cries of the parrots, and occasionally by the trumpeting of wild elephants. The puram poetry on warfare and kingship on the other hand refers to the war elephant specifically. The poems boast of august and powerful kings who, sat on mighty tuskers, engaged variously in march pasts, displays of royal splendour, ritual processions, sieges, battles and such. A poem from the Purananuru indicates that elephant-drawn chariots mounted with shields saw frequent use during conquests (no. 12 in Ramanujan 1985, 113). It is well known in any case that horses were scarce in the Tamilakam and it was difficult to get them exported, so Chola, Pandya and Chera kings rode on elephants during times of peace and war.

And Beyond the Subcontinent

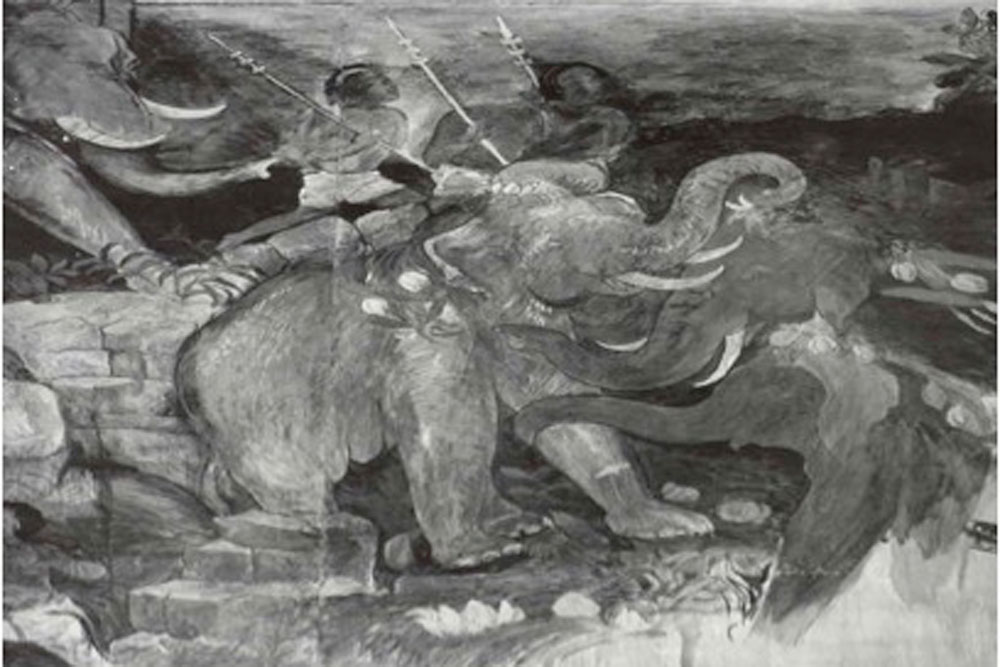

Trade, diplomacy and religious exchange often entail a rich traffic in ideas and knowledge, and so it was with the case of the war elephant. There is definite evidence from at least the end of the second quarter of the third century BCE that with the advent of Buddhism and because of the presence of both Mauryan as also South Indian diplomatic missions the institution of the war elephant had materialised in Sri Lanka as well. The Mahavamsa tells us that when princess Sanghamitta arrived with a shoot of the Bodhi tree on the island, a procession of the fourfold army (caturangini sena) headed by king Tissa and a large body of monks were present to receive the bhikkhuni (MV 18–19). It is likely the idea of the thing had travelled; it is not very probable that elephants were shipped from India to Sri Lanka. A difficult and risky endeavour in the first, it would have made no sense in the second given the dense forests of the island were already peopled thickly by elephants. The Mahavamsa also narrates a riveting account of how surrounded by his fourfold army the king Duttagamani did battle with the Chola forces under Elara from atop his mighty war elephant Kandula (MV 25.81).

The elephant sustained in Sri Lanka right down till the medieval period and it is understood that by the first few centuries of the Common Era it had made its way from the island to Southeast Asia. There is proof of long-distance contact with the immediate subcontinent as well, and historians argue that by the end of the first century CE the war elephant had travelled from North India to places like Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam and Java (Mabbett 1977, 143-161; Trautmann 2015, 251). As kingdoms flourished across continental Southeast Asia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra about the same time period, they drew upon Brahmanical traditions and Indian theories of kingship to ground their political projects. Integral to the same process was the adoption of relevant techniques for war practised in the subcontinent and of deliberate attempts at importing and appropriating the knowledge needed to establish the institution of the war elephant. As the fashion to emulate Indian ideals of kingship came into vogue so too did the war elephant proliferate given its inextricable association with royalty. This was not a very difficult thing to achieve given wild elephants were to be found in plentiful numbers in the forested regions of Southeast Asia.

Patrick Olivelle points out that “perhaps the more significant spread of the war elephant was to the western armies” (Olivelle 2016). After Alexander’s conquests in the third century BCE, the war elephant had begun to figure as an aspect of the military machinery of the Macedonians. From them the knowledge of the techniques essential for the cultivation of the elephant for war spread to the Greeks and the Persians over the next few centuries. The ready acceptance of such knowledge by their respective empires had essentially to do with the adoption of prudent and practical battle tactics in the face of shifting modes of conflict; as one state took up the war elephant for its purposes another was forced to do so as well to keep up with the competition. Eventually, the mahout and his ward came to be appropriated even by those powers which held or would in time hold sway over the world: the Carthaginians, the Romans and the Ghaznavid Turks (only with the last power do we know for sure that Indian mahouts were actually imported, see Goukowsky 1972). In the case of medieval Asia, chronicles generated by scholars attached to royal courts attest to the superlative role played by the war elephant. The fourteenth century historian Ziauddin Barani in a discussion of the subject in his Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, for instance, adduces a popular parable which put forth that a single elephant was worth five hundred horses in battle to make the point (Khan 1862, 53 in Raza 2012, 212). Two centuries down the line Abu’l Fazl repeats the gesture; this very same exaggeration is picked up by the Ain-i Akbari (Raza 2012, 212, 13; Fuller and Khallaque 1960, 56-70). It hardly needs pointing out that such fulsome characterisations concerning the performance of the elephant on the battlefield were in all likelihood fed simultaneously by knowledge of the effect to which rulers like Khusrau Parvez, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni or even Alauddin Khilji put their elephant corps and by memories of the successes they courted as a consequence.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba