The Lost Film

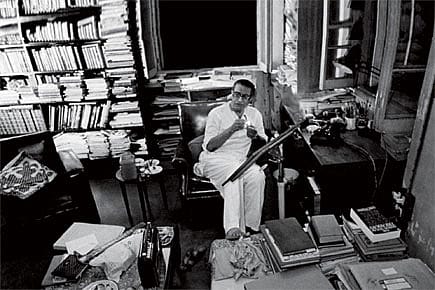

Satyajit Ray's banned documentary Sikkim made an all-too-brief return at the Kolkata film fest. Magical for those who caught it, tragic for those who didn't.

Satyajit Ray's banned documentary Sikkim made an all-too-brief return at the Kolkata film fest. Magical for those who caught it, tragic for those who didn't.

After being shrouded for nearly 40 years in mystery and controversy, Satyajit Ray's 60 minute colour documentary Sikkim (1971) premiered at the 16th Kolkata International Film Festival (Kiff) with two screenings, one on its inaugural day and the other on the final day. An interim stay order by the district court of Gangtok had forced festival authorities to suspend shows of the film that was scheduled for daily screening. However, an out-of-court settlement saved the day for Kiff when the Art and Cultural Trust of Sikkim permitted a second screening against a one-time payment of Rs 20,000.

Long queues for tickets and requests for passes testified to the eagerness with which Ray aficionados wanted to catch this piece of Ray celluloid. No other film, documentary or full-length feature made by the Calcutta maestro has been kept away from audiences with such obstinacy for so long.

The documentary, the second of five made by Ray, was commissioned by the Chogyal (king) of Sikkim, Palden Thondup Namgyal and his American wife Hope Cooke, as a tribute to the Himalayan kingdom, the aim being to lure tourists. But the original film was banned on two counts. First, by the Chogyal, who found scenes showing the royalty in bad light objectionable, and second, by the Government of India, once the kingdom was annexed to the Indian Union in 1975 under controversial circumstances.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

What was screened at Kiff on the inaugural day was an hour-long DVD version of Sikkim that was with the cameraperson Soumendu Roy. The audience's sense of anticipation had been heightened by what Ray himself had said about the film. Its opening shot, in Ray's own description, pans its way across two approaching ropeway cartridges on a wet day in Sikkim. "While they are reaching this point, I cut to a shot of a piece of telegraph wire," he had said, "It's raining and there are two drops of rain approaching on a downward curve. It's a very poetic seven minutes. And the end is also very lively, very optimistic, with children, happy, laughing, smoking, singing. The whole thing builds up into a paean of praise for the place."

And indeed, Ray's voiceover leads the audience to a mesmerising account of this Himalayan kingdom's story. Pictorially, the film bears Ray's unmistakable signature as it scans Sikkim's mountainscape together with its wild growth of orchids, rhododendrons, bamboos, and ferns alongside the river Teesta. Ray's camera also focuses on the cultural diversity of this Himalayan kingdom bustling with Nepalese, Bhutias and Lepchas. Sikkim is a multi-lingual state where assorted people are shown to live harmoniously, and Nepali appears the lingua franca.

The film's second half focuses on an annual royal festival to mark the king's birthday which features a dance that symbolises a victory over evil and its dividend of peace. Performed by Chaam monks and accompanied by chants and music, it has enactments of episodes from Buddhist mythology interspersed with comic relief, before it all culminates in effigies of flour, wood and paper being sent up in flames.

What remained of the controversial shots in the version screened at Kiff was a part of the palace festivities with royal guests at a grand feast while cooks and servants wash cutlery in a quiet corner and use their hands to eat a humble meal of rice, pork and a local brew. The royal couple had objected to several scenes, including one of an open-air garden party thrown by them where a table is laid out for aristocratic Sikkimese and foreign guests. Ray is said to have juxtaposed these scenes with shots of the poor and starving scrambling around in the biting cold for leftovers in the darkness outside the palace. Such depictions of disparity did not suit the royal idea of a documentary, it turns out.

Writes Andrew Robinson in his book Satyajit Ray: An Inner Eye: 'He was compelled to make about 40 per cent of the film into something 'bureaucratic with statistical information' and a disproportionate emphasis on the Sikkimese population instead of on the Nepalese, as would have been appropriate given the latter's actual preponderance in the state. He remembers one scene in particular that got cut out when he showed his original version to the Chogyal and his wife. It showed a party with a senior bureaucrat shot in a 'not very flattering way—he was eating noodles, I think'. Hope Cooke kept saying 'That's wicked! That's wicked!' and Ray knew that this was one part of his film that would never make it to the finished version.'

The Government of India , on its part, banned the film because, 'The film showed Sikkim as a monarchy, with shots of people prostrating themselves before the Chogyal.' 'And that's now democratic Indian territory,' chuckles Ray. 'It's not a very logical reason for banning the film because after all it shows Sikkim at a certain point in history. It doesn't claim to show Sikkim of today.''

As with his feature films, Ray's documentaries, five in all, are marked by an intense humanism and empathy for the people shown, apart from a compulsion to keep himself non-intrusive as the narrative unfolds. He once said to his friend Chidananda Dasgupta about documentaries, "What you think is unimportant, you must show what he thought and did" ('he' being the film's subject).

This ethic is evident in Ray's Rabindranath Tagore (1961), commissioned by the Central Government for the poet's birth centenary. Without any lengthy interviews or even recitations, the documentary movingly captures the poet as a young lad who hated school, accompanied his father to the hills, led a riparian life on a zamindar estate in East Bengal, and produced some of his most brilliant pieces there. The film ends with a passage on his paintings to the accompaniment of some fine music.

Likewise, Ray's eponymous documentary on his father, Sukumar Ray (1987) manages to tell his audience about the man's work mainly through dramatisations of scenes from his spoof Ramayana, among other achievements, that vivify the characters he etched and nonsense verse he wrote.

No less watchable is Bala (1976), Ray's documentary on Bala Saraswati, whom he called "the greatest Bharatanatyam dancer ever". The film has a memorable performance of the lyrical varnam, her dancing range coming across beautifully.

And The Inner Eye (1972) is a small masterpiece on his inspiration at Santiniketan, Binode Behari Mukherjee, who Ray described as someone with a "total lack of flamboyance". Mukherjee, born with poor eyesight, lost his vision totally at 54. It was during this time that he produced a fine body of work, much of it in the form of murals on the walls of various buildings at Santiniketan. The film was a search for his "inner eye, an inner vision born of long experience and devotion which the artist could call upon to come to his aid and guide his fingers", as Ray said it in his commentary.

Sikkim, in contrast, was not about any one personality, and thank God for that—for if Ray's other documentaries suffered the same fate, a treasure would've been lost to humankind.