Writing and Seeing

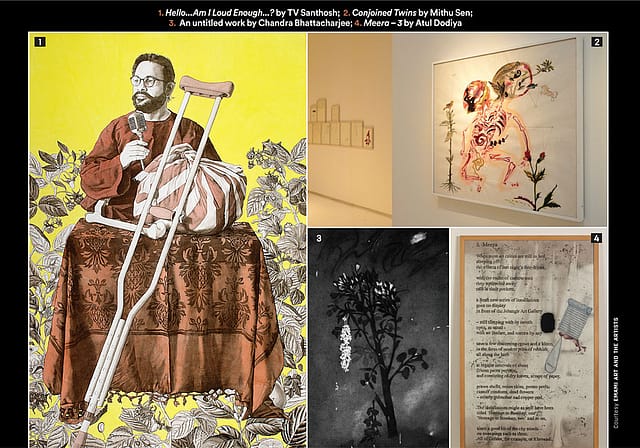

THERE'S SOMETHING primal about paper. For artists, the humble sketchpad is both a starting point for new creative journeys as well as a material with endless possibilities. Inexpensive and flexible, it is also the most easily available medium. But in today's digitalised world, when someone even as old-school as David Hockney has moved to tablet doodling, paper can seem a bit passé. Kolkata-based Emami Art gallery aims to counter that narrative. Curated by Ushmita Sahu, The Politics of Paper is an alchemic enquiry into the nature of this most conventional of artistic mediums on which artists over centuries have left their mark. The show includes works by Anju and Atul Dodiya, NS Harsha, Mithu Sen, Jagannath Panda, Prasanta Sahu, TV Santhosh, Jayashree Chakravarty and Adip Dutta. Though wide-ranging in their preoccupations and practice, this heterogeneous group has a common affection for paper. "The material is the mainstay of our concept for The Politics of Paper," stresses Ushmita. "Due to its egalitarian ethos, paper automatically releases the artists from trying to fit into a given subject. We have invited only those names who have had a genuinely long-term engagement with the medium. In many cases, the language of these artists has become iconic, inspiring the next generation. For example, Atul, Anju, Santhosh or even Mithu Sen, they all started exploring watercolour on paper decades ago, yet their approaches and aesthetics cannot be more different."

Showing in Kolkata for the first time, Atul Dodiya's Kala Ghoda poem works from 2017, sets the tone for this group exhibition. Based on Arun Kolatkar's poems, these large-scale watercolours conjoin the pleasures of the written word with the romance of old Bombay. This series of paintings were done during Mumbai's monsoon to keep the paper moist so that Atul could manipulate the spread of watercolour. Otherwise known for his pop culture-infused spectacles that evoke Bollywood and European art in equal measure, Atul Dodiya has continued to maintain an almost parallel practice that involves the use of paper over the decades. Paper has given successful artists like him "freedom from the demands of the market," Ushmita notes. More than Atul, his wife Anju Dodiya can perhaps claim a greater fidelity to the medium. Since the beginning of her career, the Mumbai-based Anju has relied on the spontaneity of paper to explore her self-image. The autobiographical The Enfolding, features an Anju-like figure holding a pencil in her hand as she gets engulfed by blank pages. Anju's concept note reads, "Paper is that terrible white that remains the joy and terror of my creative life. It envelopes, invites, chokes, frees, and allows flight."

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A similar existential gloom embodies Chandra Bhattacharjee's monochromatic charcoal drawings of flowering trees, shooting stars and fireflies hinting at the mysterious and secretive self that resides in every human being. For Bhattacharjee, paper might be an ordinary material designed for everyday use, but it retains power to awaken a "new life and meaning when an artist explores it." Ushmita observes, "There's a literary quality to his art. It's like being inside an emotionally moving scene of a dark forest full of nocturnal sounds. His art makes you think about nature." On the other hand, NS Harsha's 40-feet wide wall installation Reclaiming the Inner Space uses found cardboard cartons to caution against the growing consumerist menace.

Currently living and working from West Bengal, both Adip Dutta and Prasanta Sahu hold teaching jobs in art colleges in Kolkata and Santiniketan respectively. Born in Balasore, Odisha, Prasanta Sahu discovered the charms of paper by accident. He used to write and paint in scrapbooks and did not pursue it seriously at first. "I never exhibited them though they contained beautiful drawings. One day, I happened to revisit one of my diaries and was surprised to find that even with age they looked good. I said to myself, 'What if I do this on paper instead of the scrapbook?' That's how my journey with paper began," says Sahu, over a phone conversation from Visva-Bharati University where he works as an associate professor in the fine arts department. He says he doesn't fear paper but prefers it to canvas because, "It's a medium which allows you to be subtle as opposed to a canvas where you are tempted to pour layers and layers of colour." For him, drawing on paper is one of the fundamental things he loves about art. An electrical engineer by training, Sahu says, laughing, "I think it won't be wrong to say that I could pass in engineering in the first place thanks to my drawing skills. I spent four years making technical drawings of alternators and generators and all kinds of analytical studies as a student. I used to enjoy my playful interaction with paper and sketching. And I still do."

The 52-year-old Sahu's Harvesting – The Untold Story: A Conversation with the Land is one of the most politically charged installations in The Politics of Paper. Composed of recycled waste including tissue paper cast from plaster moulds sourced directly from vegetables, it speaks of his commitment to keep art as real as possible. "As an artist, I want to constantly introduce newer windows to look at a particular issue, in this case the farmers with small land holdings and the extremely marginalised and disadvantaged tribals," he says.

Likewise, Adip Dutta's art is a response to his immediate surroundings. Having a day job at the Rabindra Bharati University in Kolkata requires him to traverse the city, past chaotic streets, noisy hawkers, industrial units, shantytowns and what he calls "soft architecture". His primary interest lies in underlining the contradictions between the hustle and bustle of the urban spaces he encounters every day and their desolate presence—or absence as it were—when he commits them to paper. "There's a dichotomy, in the sense that I am indicating the source and then negating it in order to build an artistic ambivalence," says the 51-year-old Kolkata native. Paper encourages Dutta to work slowly and meticulously, with fine lines and dots that trail off into a "ball of energy". Describing paper as his "main medium," he says, "I select paper for its fragility after which I load it with marks. That is how the process is set into motion." Dutta believes that the most intriguing aspect of paper remains its strong association with both writing and drawing. Take Egyptian hieroglyphic systems, for example, which combine elements of writing and visuals and can be read as either—or neither. Dutta explains, "Sometimes, as in the case of Rabindranath Tagore, writing becomes an extension of drawing and vice versa. Paper is somewhere in between. It's a space for both and it helps you to switch seamlessly from one to the other."

For curator Ushmita Sahu, paper is both her past and present. As a young student pursuing art in Delhi and later at Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan through the 1990s, paper was her favourite. The show is her ode to paper-dom and she talks excitedly about it. "Paper is so intimate," she remarks. "It allows for the immediacy of mark-making and it also encourages the acceptance of 'mistakes'. It is fragile and delicate but can last for eons. It has been woven into the very fabric of human history and has proven itself to be an extremely versatile artistic vehicle." Despite technological advances of the 21st century, paper has remained an elemental presence in the lives of Ushmita and her generation. "Paper makes you feel that you know it so well. We grew up writing and scribbling on paper. We studied in it and read from it, by way of books and newsprint. I remember, as a kid, opening a new book and smelling it. The scent of fresh paper is ingrained in my psyche," she says.

PAPER IS BAD for the environment but good for art, it seems. From artists and designers down to curious children, it services all creative souls as the de facto art tool. What's more, after the lockdown there has been a sudden resurgence of interest in pulp. Ushmita admits that the idea for The Politics of Paper came to her after the lockdown of 2020-21. She noticed that homebound artists with no access to art materials had started turning to paper. Many were making their own sheets from recycled waste. "Around the same time, I was also reading about Benode Behari Mukherjee and the Santiniketan masters and their intimate engagement with tempera and watercolour on paper. Historically, the Santiniketan masters, barring Ramkinkar Baij, did not work in oil. There was also the influence of Bengal School with a certain artistic language and medium as political intervention. All these events became a catalyst of trying to look at the paper as much more than just a material. "

In tracing paper's overall evolution in the Indian context, Ushmita's encyclopaedic research yielded many personal discoveries about the various roles it has played in folk traditions, printmaking and miniatures. She also found some intriguing links between paper and nationalism during the 20th century's Bengal School movement. She explains, "The ecosystem of Indian art has its independent logic and the use of paper has followed a distinct trajectory of its own. It starts with its introduction in the 12th century in India. The illustrations on paper manuscripts replaced the earlier palm leaf paintings and these developed into the spectacular miniature painting schools with illustrated manuscripts, albums, folios and portraits. By the 19th century Bazaar schools of printmaking were well established and these looked at folk traditions, local socio-political and the European influence of the times to create an indigenous, vernacular language producing illustrations, matchbox covers, calendars etc." Lastly, there's paper's inherent connection with incendiary acts. As she points out, "One may think of protest posters and pamphlets distributed or pasted on walls in the cover of the night. It is also linked to the history of cinema and how dreams have been disseminated from the dream factories to the rural hinterland. Then there is obviously the print medium of newspapers and magazines and its massive history." Considering the legacy of paper, going 'paperless' seems a relatively impoverished future.

(The Politics of Paper runs at the Emami Art gallery, Kolkata, till March 29)