Video Saga

The Turner Prize-nominated Otolith Group is in India for the first time with a trilogy of films made over the past decade

In our movies, we have ghosts of other films, films we would've liked to make." This whisper of Kodwo Eshun, co-founder of the London-based Otolith Group, is interrupted by a voice from the next room: "Why did you leave us trapped in that village dreaming of projection?" It's the on-screen voice of the Journalist from the film being shown there.

Experimenter Art Gallery, as part of In the Year 2103, is screening The Otolith Trilogy, which was made over the last decade. The gallery chose to open the exhibition with the third film because of its special connection to Kolkata—Otolith III has, as a point of departure, Satyajit Ray's 1969 screenplay, The Alien, unfinished and steeped in unrealised characters. The Industrialist, Journalist and Boy swim across the projection screen like ghosts of Pirandello's characters, forever searching for the Director, for the moment when script becomes life, and idea finally transforms into reality. The film uses excerpts from various Ray movies as well as original footage to put together a 'premake'. The Industrialist's aims could also be the Group's—"I'm not going to make the film the Director could have made. I'm not even going to make the film he couldn't make. I'm going to film the idea." This is attempted through a constant shift of images that weave a dreamy narrative, broken into segments told through different voices.

The trilogy functions as a series of personal essays that employ archival and visual media 'fossils' to create myths of the near future, an idea the Group borrows heavily from British experimental writer JG Ballard. The Otolith Timeline video, for instance, overturns its function as a documentation of a series of chronological occurrences by slipping in fictional events, and finally ending with an entirely make-believe section that stops in the year 2103. This is what enables Otolith I and Otolith II to be historical retellings through imaginary 'relatives' of the future. In the former, Dr Usha, a fictional descendant of Anjulika Sagar (also co-founder of the Group), pieces together the evolution of our species from a 22nd-century International Space Station, suspended far away from an uninhabitable earth. The pivotal event around which the film revolves is London's 2003 anti-war protest march; a particularly beautiful moment is one that captures, amidst banners and slogans, silken white swan puppets over the crowd.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

In Otolith II, Dr Usha reads out 'letters' from Anjulika Sagar to her nani that speak of Mumbai—"Every night, I drive across the Island City looking for answers that might help me ask better questions. What is the city becoming?" It's a question that's exceedingly difficult to answer. The movie functions as an 'essay-film' that explores desire and material consumption, labour, population, relocation, and political and economic futures, the last mainly through architecture—the planned modernism of Chandigarh as opposed to the organic sprawl of Dharavi.

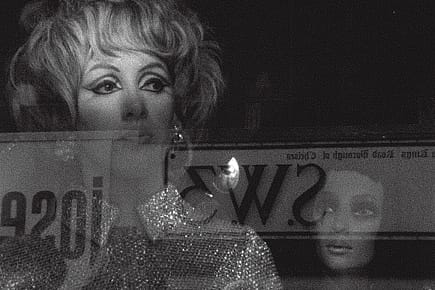

The idea of transformation also works in other, more tangible, ways in the exhibition. Otolith I and II include references to Sagar's grandmother, Anasuya Gyan-Chand, once president of the National Federation of Indian Women. The old photographs shown in the films, of her travels to Russia in the 1950s as part of a delegation, form 'Preparations', a series of black and white pictures digitally rendered as mirror-images. They are whirlpools in which various ideological strands—feminism, modernism, communism—are pulled together and held up as a sequence of re-imaginings. In the video work Communists Like Us, these same images—outings to museums, factories, schools, nurseries, laboratories, bus tours, conferences—are flashed onto a single-channel screen while the score comprises a 16-minute conversation about violence and revolution between Francis Jeanson and Veronique in Jean-Luc Godard's La Chinoise.

Given their varied background—Sagar's in anthropology and Eshun's in film theory—the Group draws upon a vast number of cultural, political, economic and social references. Although Otolith takes its name from a mechanism that exists within the inner ear, which plays a critical role in maintaining one's fundamental spatial coordinates (up, down, left and right), the group thrives on creating works infused with a sense of dislocation and disorientation.

According to Sagar, their book, A long Time Between Suns, can help clarify their ideas. The book is an archival assemblage that covers their Turner-nominated, two-venue exhibition in 2009, and also includes transcripts of dining-table discussions between Otolith members and artist Will Holder, critic and curator Anna Colin, and director of The Showroom, Emily Pethick. In one of their conversations, Eshun and Sagar say they believe "incompletion can be more productive than completion"—which explains why the trilogy, rather than offering neat linear narratives and closure, tends to spill, spread and meander, giving unfamiliar shape to our world.

The Otolith Group will show at the Experimenter Art Gallery in Kolkata till 8 January 2011