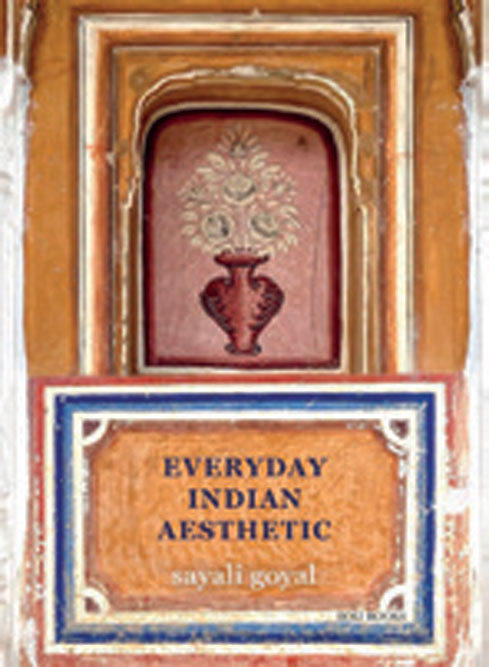

To call Everyday Indian Aesthetic (Roli Books; 432 pages; ₹2,495) a travel photography book would do it injustice. This tome holds 400 photographs by Sayali Goyal, shot across India. To flip through it is not to travel from place to place with her, rather it is to zoom in to everyday objects that often miss our attention. You see flowers cradled in a bed of leaves, sewing machines shot from above, piles of steel plates stacked against a blue wall, worn juttis foregrounded against a cement floor, layers of necklaces garlanding a faceless man, silver anklets of a woman whose feet are covered in sawdust, the frames of doors, the jaalis of windows, ascending stairs and curvaceous corridors, the vestibules of trains and pink blossoms elbowing their way through fences. Seen individually these snapshots might seem like Instagram stories but put together they are akin to a living museum. This is not the world of couture design, instead this is very much pret. Which reminds us that the everyman and everywoman is a designer, with their own eye for aesthetics. This individual design sense is made evident in the colour of their pagadi, in the toe rings donning their feet, in how they stack their wares at a shop.

This is a book that celebrates the beauty of the mundane. The see-through bamboo curtains tell of cool afternoons and blazing mornings, the buxom wooden pillars remind one of the ancestral homes of South India, the bedecked ceilings take one from Tamil Nadu to Rajasthan. By homing in on particular objects it tells us a bigger story about identity and belonging. As we rush towards a ‘modernity’ that devours the local and egests a uniform Western aesthetic, this book pays tribute to Indianness. Whether it is cherubs on a ceiling or a pigeon atop a jharokha or mosaic floors or patterned tiles. This is an aesthetic that combines skill with whimsy, imagination with geometry. Not all of it is functional, but it is mostly beautiful.

Divided into four categories or chapters, ‘Objects & Artefacts’, ‘Typography & Imagery’, ‘Adornment & Identity’ and ‘Architecture & Interiors’ Everyday Indian Aesthetic celebrates the many characteristics that make us ‘Indian’, whether it is the unabashed use of colours, or the oft-appearing geometric motifs or the widespread use of natural material. Delhi-based Goyal, who is soon heading to London for a Masters in Anthropology, says, “The book is an anthology of seven-eight years of ethnographic travels in India.” Having spent the last three years turning her body of work into a book, Goyal elaborates, “I feel like it’s not a book that you go through once. I would like to give a reference of the Oxford Dictionary. That’s the reference I gave Roli as well, when I first told them about the vision I had for the book. Because, you know how the dictionary cannot be read in a day, you keep referring to it as and when you want to enrich your vocabulary. So, this for me is a visual vocabulary book.”

“This book is about the essence of a place or an identity. By adding geographies or captions, we would have fallen under the category of a travel photography book, i didn’t want that” says Sayali Goyal, visual artist

Share this on

The visual vocabulary available to readers is only two per cent of Goyal’s work, as these are 400 photographs chosen from over a lakh. She first shared 15,000-20,000 with her publishers before they were narrowed down to a few hundred. The photos come devoid of any details as the book has no captions. Each of the four sections opens with the briefest of introductions, which adds little context. This is a book where the photos must (and do) hold their own. Goyal from the start was clear that the photographs should have no captions. She says, “I don’t want people to see this as a travel photography book, because that’s not what it is. This isn’t about photography. It is about the essence of a place or an identity. Most photo books focus a lot on the technicality, or how beautiful the photograph is, but this is more about the subject, the theme. By adding geographies, we would have fallen under the category of travel.”

The lack of captions expands the book’s scope. One does not flip through it looking for familiar places, instead one looks more closely to identify what is recognisable or not. Goyal’s travels took her from Tamil Nadu to Ladakh, Delhi to Manipur. Born in Delhi, and having spent considerable time in the capital, Jaipur, Punjab and Mumbai, Goyal does have maximum content from these regions. But she feels that as “a visual person,” she is on a “different kind of high” when she is in South India because she is “shooting 24/7”. To highlight the geographic variety of the book, Goyal and I play a guessing game, where she turns to a random page and asks me to guess its location. I often get it wrong. Which is an interesting lesson in itself as it reveals one’s preconceptions about different geographies.

Goyal shot most of these photos on her phone, having learnt the hard way. Back in 2018, when she first started travelling and shooting for her cultural platform Cocoa and Jasmine she would schlep along a large DSLR camera. But it intruded between her and her subject and made her an object of curiosity. She finds the phone to be a far friendlier device and chooses not to overedit her work. Adding, “I realise for ethnographic documentation it’s best to have a phone camera because then no one is intimidated and your process is very intuitive, which is how I like to create my work.”

Everyday Indian Aesthetic allows readers to conjure up their own interpretations as it juxtaposes one photo against another or a collage against another. This allows for the photos to speak to each other. Every reader will have her own favourite, but one which I find compelling shows an array of teatime snacks (namkeen, samosas, biscuits, gulab jamuns) laid out with symmetry in plastic plates on a synthetic floral carpet. While this photo stands on the left, the one adjoining it is a closeup of a music store, where colourful drums are piled on each other. The snacks make for a memorable photo as it is such a perfect example of Indian hospitality and the effort made to present food with care, even if it is just arranging biscuits in a spiral shape on a plate. It is a photo that speaks of both our aesthetics and our culture, where guests must be fed, and homes must be hospitable. The adjoining one complements the colours of this, and the drums waiting to be bought and played add a festive feel.

“I realise for ethnographic documentation it’s best to have a phone camera because then no one is intimidated and your process is very intuitive, which is how I like to create my work,” says Sayali Goyal

Share this on

Goyal’s own proclivities, such as her partiality to ceilings and floors, also shine through the book, as we have page after page of arresting details, such as mosaic floors, marble stairs, kolam patterns, sunlit arches, carved cornices, floral grills and tiled roofs. Goyal confesses with a laugh, “I love grill patterns. I think grills really get me excited. What gets me excited isn’t just the aesthetic of it, but also the fact that people are inspired by each other and how artisans migrated from one city to another, creating this kind of aesthetic which was adapted by a large population.” She likes the thought that artisans have spent time creating elaborate ceilings which hold no real functional value, but which someone will stare at before sinking into sleep.

This celebration of material culture is an important reminder of all that we have and all that we risk losing. The construction of every new glass and metal high-rise also tells of the demise of a haveli, which perhaps had terrazzo floors and curling balconies and intricate grills, which were created by hand. The ‘modern’ buildings of today are largely devoid of fancy and flourish, creativity and artisanship. Goyal provides a useful warning, “If we bring the heritage down, then we don’t have any stories to tell the future generation. And at the end of the day, we all need to find the sense of belonging with material and visual culture.”

/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Beautymyth1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Cover-Modi-scaled.jpg)

More Columns

I Missed A Flight Thanks To Robert Redford, Plus He Took My Magazine! Alan Moore

Robert Redford (1936-2025): Hollywood's Golden Boy Kaveree Bamzai

Surya and Co. keep Pakistan at arm’s length in Dubai Rajeev Deshpande