Of Raised Eyebrows

The story of VP Dhananjayan's struggle to break away from Kalakshetra and establish himself as a solo male Bharata Natyam dancer

'Please do not leave Kalakshetra, there is no life for male dancers outside Kalakshetra.' This was the advice given by Mohan Khokar, one of Kalakshetra's earliest male students, to VP Dhananjayan. When circumstances resulted in Dhananjayan leaving—despite never having intended to—he took it as a challenge: He would demonstrate that it was possible to make a career in dance and succeed outside Kalakshetra. However, it was easier thought than done. There were many impediments along the way.

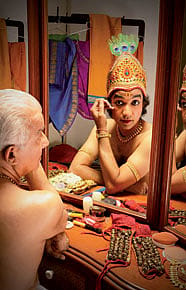

First, to step into the great unknown beyond the gates of Kalakshetra was daunting in itself. Then came the choice of disciplines. Two roads branched out in front of him, Kathakali and Bharata Natyam. Of the two, the more demanding was Kathakali. Dhananjayan had been fully prepared by an exacting [Chandu Panikker] Asan to meet the rigorous standards of that art-form. He had the looks and radiated a certain innate goodness in abhinaya, a quality of peaceful sattwa that earned him the 'pachcha' roles of the gods, his face painted 'green' and wearing the large circular crowns as Rama or Vishnu. However, one could not be a solo Kathakali dancer; it required a group, in order to present the plays. That would mean returning to Kerala, but Dhananjayan and [his wife] Shanta were happy in Madras and already had a few students.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The great Guru Gopinath, whom Dhananjayan admired a lot, had paved a unique path when he drew from his training as a Kathakali dancer to create his own style of dance, Kerala Natanam, way back in 1931. However, Dhananjayan was too steeped in Kalakshetra's aesthetic to shift to another style.

Could he make a living from Bharata Natyam then?

In the late sixties, there were no male dancers in Bharata Natyam whose path Dhananjayan could readily follow. The one world-famous Indian male dancer, whom everyone had heard of, Uday Shankar, had evolved his own unique style. Ram Gopal, who had studied Kathakali, Bharata Natyam and Kathak from the best of gurus, had shifted base to London, and drew from all these disciplines in his presentations. Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury, born in Madras, was to find his fame and fortune in America. They had all established their careers outside India. Would Madras, the part 'outside' Kalakshetra, offer him any scope to perform?

It was a bleak scenario.

The earlier patrons of the arts, royal families and moneyed zamindars spread across the fertile lands of the Madras Presidency, had dwindled. In the city, Carnatic music was kept alive by self-financing associations called sabhas. Funded by rich industrialists and wealthy Madras-based professionals, these were primarily associations of the lovers and connoisseurs of Carnatic music. It was only lately, with the growing social acceptance of Bharata Natyam, that they had started presenting dance performances as well. "In those days people paid to watch natya performances. When Balasaraswati or Kamala or Vyjayantimala danced, tickets would be sold out. Most of the sabhas… The Music Academy, Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha, Sri Brahma Gana Sabha, Indian Fine Arts Society… earned much of their annual revenue from Bharata Natyam performances," explained Dhananjayan.

Certainly, the ambience, the location and indeed the audience at these sabha performances were very different from the mostly male audience that a sadir [or solo] performance [by devadasis] would have attracted in a salon.

While women did attend dance performances at sabhas, it did not necessarily translate into an audience that wanted to watch a man dance. The established sabhas were not particularly interested in presenting a male dancer performing Bharata Natyam. In their thinking, if a young nubile girl danced, at the very least, her lissome body would be on display even if she had no great talent.

The Music Academy, long considered the premier sabha, "did not recognise us at all. They do not have a tradition of inviting male dancers nor couples. Its Secretary TS Parthasarathy who was a great admirer of ours and helped us a lot, said 'My hands are tied because of the policies.'"

Might a woman's presence alongside his make him more acceptable to the organisers of shows?

Dhananjayan was married to a dancer who shared the same foundation and training from childhood. Each trying to establish an individual career in dance did not seem a viable proposition. It seemed inevitable that Shanta and he would dance together, with all the experience that Kalakshetra had given them when it came to precise coordination on stage. Today they are known as The Dhananjayans, the dancing couple, but at the time they were courting in Kalakshetra, did they ever dream of this? "Never!" confessed Shanta. "I never ever thought that we would leave, and establish ourselves as a duo!"

A dancer's repertoire showcases his skills. Each item presented on stage needs to be chosen with care and for a reason. Having decided to project himself as a Bharata Natyam dancer, Dhananjayan had to create a core repertoire.

Balagopal and he, as boys in Kalakshetra, had not been encouraged to dance the solo Bharata Natyam repertoire. "We were considered mainly Kathakali artists, who were taught Bharata Natyam so as to dance in the dramas. While I had done minor items in class which were male oriented, there were no suitable songs for boys. Only Rupamu joochi, a varnam in praise of Shiva. We did that varnam, dropping the line suma shara mulache where the nayika complains of being struck by the flower-arrows of Cupid. The padams were Natanam adinar, about the vigorous dance of Shiva, or the Ashtapadi Vadasiyadi, where Krishna cajoles an angry Radha. Balan and I learnt items such as the tillana on our own initiative, which did not go down well with some of the teachers. But because we were doing every possible role in the dance-dramas, the technical grounding was very strong. We could learn anything later on."

It meant that Dhananjayan had to find suitable themes and choreograph them in a way that highlighted his strengths as a dancer. Rukmini Devi's objections to Shanta and him using the repertoire learnt at Kalakshetra served as an additional spur to creativity. Dhananjayan, already used to doing impromptu variations in his performances, now concentrated on crystallising his approach to choreography.

"When we started performing on our own, outside, the Bharata Natyam repertoire was limited to the time-tested margam. The standard presentation from alarippu to tillana was becoming a little boring for the audience. So I thought we must develop a new repertoire. I came up with Natyanjali which has all the adavu patterns, basic tala beats and major mudras. A three-in-one introduction to Bharata Natyam, the way the todayam is a foretaste of Kathakali. For the audience, it was something exciting and different, with the jugalbandi between the percussionist and the dancer at the end. Initially Kalakshetra criticised me. They said he has changed the traditional margam but people liked it.

"We started doing many new combinations of movements, such as in the Hindolam jatiswaram I choreographed in 1968. In Nrittaswaravali, instead of the usual jatiswaram, we used a lot of cross rhythms."

"Then came the choice of varnam, the centrepiece of a show. I thought to myself… I am a man, what can I express best? I did not want to do the varnams with the nayika bhava, from the heroine's point of view. I always felt that, even when we were learning them in Kalakshetra. Athai did not want us to do Manavi or Sakhiye, the prevalent varnams with the nayika bhava or lovelorn shringara-in-separation. These were traditional varnams performed by the devadasis who were women and the words were suitable to that context. She thought shringara pada varnams were not very appropriate for boys but she did not venture to choreograph anything suitable for us. That is why we used to do Rupamu joochi, with more of bhakti, as men."

Turaiyur Rajagopala Sharma, a gifted musician, had composed an Atana varnam suffused with Krishna bhakti. When he approached Rukmini Devi with it, she said it was not suitable for Bharata Natyam, as some of the words came too fast, packed together. "So she rejected it. I took it as a challenge! The beautiful thing was it had all the Krishna stories in it… natyam bhaktivivardhanam…so I could bring bhakti in with this item. When I did it, I deviated from the usual kind of composition required in varnams where different interpretations of each word were done, not much of sanchari, the extended depiction of an idea or situation. So I used sanchari to depict the stories related to Krishna that could be easily understood by people and I decided to call it nrityopahaaram.

"When I announced it in place of the varnam, people came out of curiosity…what is this, what is Dhananjayan doing? The stories were liked a lot by the connoisseurs but the famous critic Subbudu remarked, 'Oh, Dhananjayan is doing abhinaya for swaras,' but when I explained it is not so, I am using the musical notes or swaras to communicate some ideas, then he said, 'That's good.'"

What Dhananjayan had done was link body movements that mimicked activities such as swimming or playing with a ball with plain musical notes (instead of pairing notes with abstract body movements known as adavus). It became so popular with the audience, this varnam was a regular feature in their performances. With time, the criticism dropped away. Other dancers adopted the idea.

However, there was a core issue facing Dhananjayan, just as it had faced Rukmini Devi in the thirties, related to the genre of musical compositions called padams and javalis that belonged to the devadasi repertoire.

The traditional corpus of songs performed by the devadasis expressed feelings from a feminine viewpoint. To enter any one of the situations in these padams is to first take on the role of a woman, and then within that role, portray convincingly the specific character demanded by the song. For a man performing Bharata Natyam, there is the added challenge of the instrument of a male body.

This was the two-edged problem that faced Dhananjayan when he left Kalakshetra and tried to build a repertoire suitable for a man. It continues to be a factor that every professional male dancer grapples with when putting together a repertoire: the corpus of traditional songs that explore shringara are heroine-predominant.

Dhananjayan has strong views on this. "If at all I do such a piece, I must do it as though I were a female doing it. As a character, you have to do it that way. I cannot do a heroine in a padam in a manly way. That would be incongruous! Nowadays at Kalakshetra, they do teach some viraha items, dealing with the pain and longing born of separation between lovers… Kshetragna padams such as Bala Vinave…but when the boys do it, it looks like a bhakta or devotee doing it, not like a female nayika doing it. They are just taking the words and interpreting it like a man…they do not change themselves into a nayika. So the sambhoga shringara, the expression of sexual fulfillment, does not come through, I feel."

In his role as guru to hundreds of girls, children when they started learning from him, Dhananjayan had to decide whether or not he would teach them many of these pieces. He had left Kalakshetra; he no longer had to follow Rukmini Devi's views in this matter. On the other hand, would conservative middle-class parents continue to send their daughters to him if he taught such items? Dhananjayan decided to align with the Kalakshetra perspective, finding it to be consonant with his own views on emphasising bhakti or devotion.

So, "For the second half of the programme…I did a lot of Thyagaraja and Swati Thirunal compositions. In Kalakshetra, they never chose to perform Thyagaraja's kirtanas except Rara sita. I do not know why Athai did not…I think she felt there is only bhakti in them, but I have shown that even in bhakti there is so much variety.

"I also did the ashtapadis where Krishna's feelings are explored.

Men also can express their feelings, not women alone! I chose lyrics that lent themselves to being portrayed by a man and it worked! People paid me all sorts of compliments, 'When you do it, you do it as a man should…' 'Your items are so manly, we appreciate it…'"

In an interview he explained, "I avoid seductive sringara which the critics talk about as being synonymous with Bharata Natyam. Mine is an approach in which bhakti is the dominant force. I consider sringara itself to be an aspect of the all-embracing bhakti."

He did choose select Kshetragna padams to teach his students, but only when they reached a certain maturity. As the times get more permissive, it is possible for dancers today to present some of the more explicit padams without facing the kind of approbation they might have in the thirties. Presented as human-interest situations that reveal the various shades of intimacy between men and women, they do not attract the judgement that the dancer has an immoral or sexually promiscuous world-view.