Does He Mean It?

Aamir Khan has his audience just right in Satyamev Jayate, but there are some inconvenient truths about the show.

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

|

07 Jun, 2012

|

07 Jun, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/aamir-1_0.jpg)

Aamir Khan has his audience just right in Satyamev Jayate, but there are some inconvenient truths about the show.

Three years ago, Harish Iyer, a young advertising professional from Mumbai, wrote a piece about his life in Open magazine. This is how it began: ‘I was seven years old when it started. I was at a relative’s home. His wife was also there. As always, he wanted to give me a bath. He soaped me to a rich lather and suddenly started playing with my penis. I didn’t know how to react, but didn’t mind it. I think it felt nice, though weird. He asked me to do the same to him and I obliged. He then asked me to suck his penis. I was repelled by it. He forced his penis into my mouth. I moved away and started crying loudly. He told me he’d kill me and everyone in his family if I didn’t shut up. He then asked me to suck his penis again, and this time, I did it till he spurted on my face. There was a knock at the door then. It was his wife. “I will be back in a while,” she said from outside. He lifted me and took me out. He pushed me on the cot, turned me around and then raped me. He continued to rape me for 11 more years.’

After we had finished editing the piece, we sent it back to him to recheck if he was alright with such a graphic description. He had no doubts about it. This was not the first time Harish was speaking about his abuse or about how common child abuse was in India. He had been writing about it, his own experience had been written about before and he gave talks in colleges where other students came up to him and told him how they had been abused. Often it was the first time they were talking about it. There was even a feature film—I Am, directed by Onir—that featured Harish’s story. But all that put together would have made barely a ripple compared to 10 minutes of airtime in Satyamev Jayate. Harish himself noted in his blog that he’d received over 6,000 mails within two days of the episode airing. Over 1,000 of those were from child abuse victims asking him for help.

There have been talk shows before, but Satyamev Jayate is something of a landmark for Indian television and the reason is Aamir Khan. It’s not the most popular show ever. Its TRPs are lower than Kaun Banega Crorepati and saas-bahu serials. It is also true that there have been numerous shows like this before. The news channels too have been doing documentaries and features touching upon these issues. The show itself is not pathbreaking investigation. Nearly every case or statistic shown has been widely reported and has been in the public domain. There is really no fresh material being introduced on these shows. The material is being cut and tailored meticulously for the Indian television audience. Take Harish Iyer’s case. He coped with years of abuse by finding a make-believe world within him. He wrote in his Open article, ‘I became reserved though I did have friends—a tree near my house, the chirping birds, the flies, the ants, the lizards, they were all mine, and I loved them immensely. With them, I blabbered. Anything to be myself.’ He also spoke about how at a later stage in life, his dog was his greatest support. But television needs to keep things simple. The highlight was on two elements—the dog and a fantasy friend in Sridevi.

Then there is what many find jarring—Aamir’s reactions as the victims narrate their experiences when he interviews them. Surely these are not stories he is hearing for the first time. He must have heard them repeatedly. There would have been rehearsals and scripts and all the planning that goes into any such enterprise. You can understand an outpouring of emotion once in a while, but his tears well up with clockwork regularity. The value of a superstar crying on television is limitless. As someone known to be a good actor, his own reputation condemns him. Others find it half genuine—as if he feels it and then, as a good artiste, wonders how he can exploit the feeling. But try asking a random sample of people who watch the show, and they can see the superstar do no wrong.

Satyamev Jayate takes on a social evil but does not bother to scratch under its surface—details are complicated. Harish Iyer is a homosexual but that finds no mention on the show. The episode on honour killings featured the mother of Rizwan Rahman, a software engineer from Kolkata who had eloped with the daughter of Ashok Todi, a powerful Kolkata businessman. Rizwan was found dead on the railway tracks after being hounded by both the police and thugs. It is gut-wrenching to hear the frail old woman talking about her son’s breakdown. She speaks about consoling her son, of how she told him as he curled up in terror that no harm would come to him as long she was there and that she wouldn’t allow it. And later, as she is recounting more memories, she breaks down remembering that she did not even get to see him before his death because he was staying in her sister’s home. And there you are, a viewer sitting in the sofa of your living room, your emotions driven to a crest, and on a screen in your mind the scene getting real, and then… Aamir asks her for her opinion on love and she mouths a cliché and everything becomes just melodrama.

How do we slot Satyamev Jayate? No other show in recent times has managed to bulldoze its way into the social consciousness of Indians as Satyamev Jayate has done. What peculiar concoction is it, then: an Oprah meets Bollywood meets a Kyunki serial? Or is it just a formula that Aamir Khan has perfected in films and has now taken lock, stock and barrel to the small screen?

Satyamev Jayate is brilliant and flawed at the same time. It has the stamp of Aamir as we have seen him over the past ten years, using elements that have made his movies what they are—plot-driven, serious, but also, beyond a point, shallow entertainment. It walks the line between commercial and critical, it doesn’t fit the mould and yet is hugely popular, and is a guaranteed money-spinner. It’s a fine balance and no one except Aamir has pulled it off. In the mid-2000s, the other Khans also tried their hand at this formula. Shah Rukh’s last such experiment was Paheli in 2005. Salman Khan had Phir Milenge. Amitabh is now forced to do offbeat movies to stay relevant, but at his peak, when did you ever see him doing anything non-mainstream?

Satyamev Jayate is understated and it works for it. It was impressive how the show began with no bursting lights or clanging cymbals. Aamir’s first appearance on the small screen was at most a little cheesy—walking on the beach, strains of Hindustani music in the background, writing on the sand, an Urdu couplet, a voice laden with flat gravitas explaining why he was doing the show, and so forth. And then it shows the footage of a woman who is described just as a mother. She is shown at her residence in Ahmedabad with her daughter and a hint is dropped that the daughter is special. Cut to the studio with Aamir talking to her. As he questions her, it gradually becomes apparent this is no ordinary woman but someone to whom horrific things have happened. She talks about becoming pregnant, her in-laws and husband taking her for a check-up to a colluding doctor, who checks the gender of the foetus and then, without her knowledge or consent, aborts it. And they keep doing this to her year after year until she resists. In the magazine business, an episode of Satyamev Jayate would be known as a news feature, the woman’s story an anecdote—a small startling story designed to make a point. With any other Khan (especially Shah Rukh) or Bachchan, their presence would have overpowered the unfolding story. It does not happen with Aamir and that is one of the toughest acts for a superstar—to remain in the background.

But what is also inescapable is that Satyamev Jayate plays it safe. In the dowry episode, it steers clear of showing any culpability on the part of parents who pay the dowry. They show a parent whose daughter committed suicide after being taunted as ugly by her husband and in-laws. The parents of the girl even paid readily for a cosmetic surgery because the husband demanded it. But if they are victims of a deep-rooted tradition, then doesn’t it also apply to those who demand dowry? But that would be a nuance and shades of grey take up time. The child abuse episode conveniently ignored that fathers are responsible in many instances. In the female foeticide episode, it deliberately only highlights women who were coerced into killing their unborn whereas in many cases mothers are a willing party to it. Satyamev Jayate wants to shock but not at the risk of alienating its audience.

But the show could not have been any other way. Bollywood knows it well—black and white is good business; shades of grey are bad for ticket sales. Also, we are so immersed in self-interest that it is practically impossible to arouse us except through entertainment. The middle class especially is conditioned to be insular and for good reasons. India makes ordinary day-to-day living such a misery that few have the luxury to worry about things that don’t directly impinge on their lives. The simplest of things, like the medicine you are entitled to in a government hospital or getting a ration card, is an ordeal. The exercise of any social conscience is a road into a frustrating maze. We are good at participating when everyone else is participating because there is safety in numbers. But, you also know, once they see you alone, the system is designed to viciously beat you into submission. It is the reason that so many turn up for a rally by Anna Hazare but when it comes to manning his organisation, there is just a handful. Only people with thick skin, like politicians and activists, have the ability to actually participate in society. It is also the reason why you see Aamir pop in and out of activism. In a western country, politics would have been a natural extension to his personality. But here it is only an option for desperate film stars who have lost their standing in Bollywood and need a new identity without getting their hands dirty. And if you remember how Gujarat made Aamir pay for commenting on the Narmada Andolan, you know that even he was not immune. And if he was not, then who is?

In such a country, to be courageous is to invite trouble from everywhere. You will get censored, persecuted and, worse, ignored. The only thing an Indian television audience demands is momentary respite from their daily hell. They want to get angry and self-righteous because that is also a form of entertainment. But to tell them that their father may be a child molester is the surest way to make them reach for the remote and never return to the show. Satyamev Jayate dumbs it down because that is as much the audience can take. It is also the reason that while there will be a few people touched by the show, a few court cases fast-tracked and a few ills remedied, nothing of any permanence will come of it in the long run.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

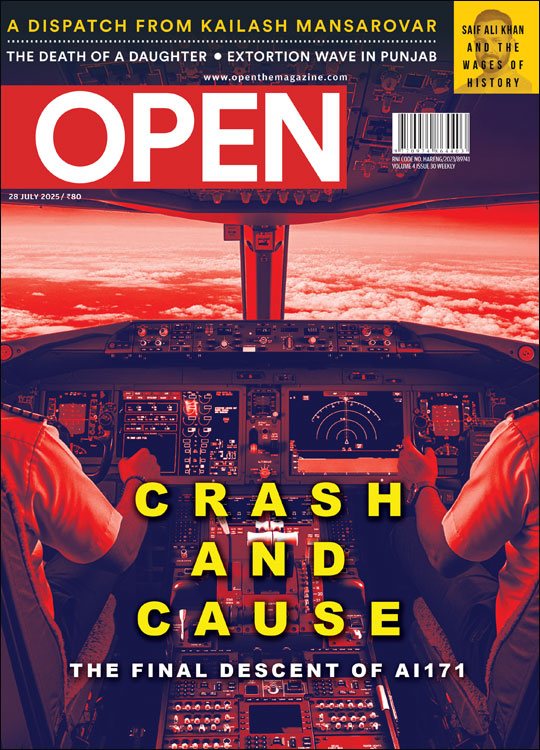

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba