Clothes Maketh a Nation

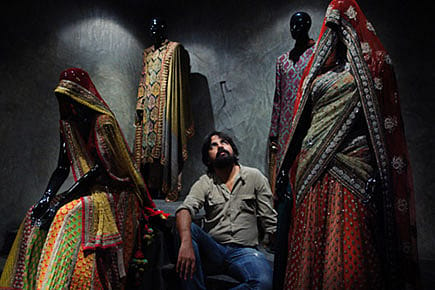

Fashion designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee and his idea of Indianness

The day Anna Hazare's movement reached a feverish pitch in Delhi, fashion designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee was administering final touches to his latest collection. When unveiled later that evening, at the recently concluded Fashion Week in Mumbai, the handcrafted clothing line would mark a celebration of India's composite culture. There was certainly an infectious optimism in the air, evoked by Hindustani classical music, a standalone Kathak performance, and, of course, the countless fashionable heads in Gandhi caps. Sabyasachi, however, insists he didn't intend his collection to coincide with the Anna movement. "Such gimmicks don't last. What does is a passionate conviction in your work," he says.

"I am always trying to tell Indian stories," he says, "and if my clothing fails to do that, it doesn't make me very happy." The designer's decade-long journey in reviving Indian handlooms, as also the Indian way of dressing, has resulted in his being often referred to as the 'most Indian of all designers'—a tag he wears proudly. "I am a revivalist. Soon, I will start calling myself an anthropologist," he jokes.

It's been several years since Sabyasachi gave up, instinctively, the chase for 'White' consumers, to concentrate purely on the demands of Indian women. Along the way, his focus on khadi and jamdani, his love for ikkat and block prints, and his signature saris with borders have acted as stimuli for Indian handloom industries, while also infusing his fashion shows with a certain rustic earthiness.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

"Once (photographer) Raghu Rai told me he wanted to see one sari of mine without borders. I couldn't find any," he laughs, "My team jokes that when we have our first advertisement, we should carry the tagline, 'Mere paas border hai'." Jokes apart, these 'saris with borders' that he's become famous for, no less because actresses Rani Mukerji and Vidya Balan are often seen in them, have people ready to shell out unimaginable sums of money. Interestingly, they have their roots in his childhood years, in the sleepy city of Kolkata. "There was a school near home called Kamala Girls School, where girls would wear white saris with blue borders. That's probably how I first fell in love with saris," he says.

Over the past few years, Sabyasachi says he's been noticing a cultural renaissance in India. Seen through his viewfinder, this will be as significant in its impact as the 14th century Italian Renaissance. "Architecture, music, films, art, lifestyle and certainly fashion—all these fields will chip in to this renaissance. There's so much potential within this country that those living outside are taking a U-turn to come back home," he says. In tune with this, he's also dabbling with the idea of designing public spaces and art installations. "For you to be able to allow a cultural revolution to bloom, you must have good public places that evoke those thoughts in people. It can be in the form of a park, restaurant or cafe," he says, reminding us that it was in Kolkata's Coffee House that the city had its most intellectual discussions.

He also fantasises using fashion, or rather clothes, to create the sanguine future of a united India. "When Gandhiji started the Swadeshi movement, the idea was to connect India visually. Today, when you step into the streets of Bombay, you could be anywhere in the world. But if you are in Rajasthan and if you step outside Jaipur, you would know that you are in Rajasthan," he says.

To make his dream a reality, he says he has even encouraged some corporate firms to reserve Fridays as 'India Day', allowing their staff an opportunity to sport Indian clothing. This, says the designer, would not only give a boost to the handloom sector, thereby "uplifting India's under-developed belt and generating employment", but also bring Indians psychologically closer. "When two women wear saris in Paris, our visual identity tells us that they are Indians and they immediately strike connections. Why can't such bonding arise here? Just imagine thousands and thousands of commuters at CST station going to work in Indian clothes."

As the years go by, Sabyasachi's work is also acquiring a fiercely socialist bent. In his factory in Kolkata, there are more men than machines working. Sabyasachi's explanation: "If a machine can do the work of five men, let's replace the machine with five men."

The mindless display of pelf in big cities is also something Sabyasachi has a distaste for. So, each time he shows in Mumbai or Delhi, he wastes little time in rushing back home. "Kolkata is a city almost like a village—that's a wonderful existence to have. If I were in Bombay or Delhi, the arrogance would get to me," he says. However, he believes big cities cannot corrupt him anymore, for he's too "old" (at a sprightly 36) for that. "My curve has gone too far now; it can't break or shake me. But if I were starting out or in my growing-up years, I would have got sucked into the vicious cycle of partying, of getting the media to notice me—I know so many people who get bothered if they don't make it to Page 3. I almost get embarrassed if my pictures are there," he says.

It is Kolkata (a place where he has his own "space and time to think and breathe") that is his infinite source of inspiration. "Kolkata never allowed my creative ego to grow. It has grounded me more than I realise," he says.

However, despite being in the fashion industry for over 10 years now, he feels limited by its scope of expression. "Fashion has a sense of urgency— 'Buy me'; 'This is my latest line.' Why this pressure to succumb to seasonal trends? Fashion is unkind because it's a disciplinarian school of thought that will push you to perform, and the day you break your ankle, it will throw you out. Very early in life, I realised that I didn't want to die out that way. I want to bow out with dignity and peace," says Sabyasachi