Candid Wedding

The big shutterbug shift from posed stiffness to emotional melodrama

WEDDING PHOTOGRAPHY hasn't always been a thinking man's profession. After all, getting heavily decked up auntyjis and mausijis to pose for family portraits wasn't really considered high art. But then, boom, globalisation hit the scene, and images of weddings as aesthetic compositions—even stylised photojournalism—started making their way in. There was John Prutch's award winning photograph of a barefoot bride with a horse in the background, or Carl Walsh's creative image of a wedding guest wearing rainbow striped boots, to stir things up.

Then, by happy coincidence, came the era of the Big Fat Bollywood wedding! Screens would light up with dance and drama for sangeet and mehendi ceremonies. What started with the 206 minute long wedding saga, Hum Aapke Hain Kaun, was followed by a rash of similar film sequences. Suddenly, every bride wanted to look like Madhuri Dixit and every guest wanted to be part of a Monsoon Wedding style drama. Melodrama was now what bridal dreams were made of.

An economic boom ushered in an age of exhibitionism, as Indians dropped their inhibitions to turn into extroverts, even show-offs. It transformed wedding photography. "Indian weddings became more and more extravagant. There were destination weddings, theme weddings, and royal weddings! All this brought about the urge to capture the lavish details frame by frame," says Rajnish Rathi, editor, Wedding Affair.

From dank studios located in shoddy bylanes, wedding photography was transported to stylish offices where highly trained photographers and their crew went about their task with fresh artistic energy. This prompted more and more people to specialise in it. Even veterans like Raghu Rai got enamoured of wedding nuances—even if largely for the cultural aspects.

Dharmendra

28 Nov 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 49

The first action hero

It spelt newer roles in the profession, too. Now you have a wedding photography director and jimmy jib handler to manage the event. Money was no issue. "The services of a photographer for a really elaborate wedding would cost around a lakh. If you use jimmy jibs, which are cameras mounted on cranes to get aerial shots of the wedding, the cost would increase by Rs 75,000," says wedding industry consultant Meher Sarid.

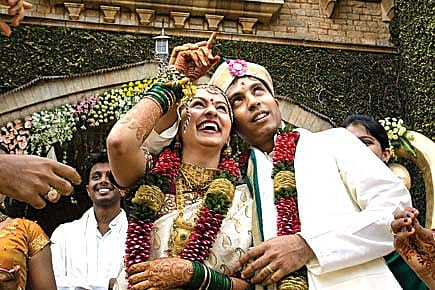

Capturing candid moments, with all the emotional highs and backstage drama, is highly fashionable now. The gush of the sangeet, the mother gazing wistfully at her daughter's cousins rehearsing Bollywood moves for the dance evening, the hilarious trip-ups—it's all open to capture. "You shouldn't stop yourself capturing the funny, silly, dramatic moments. It's very important to be able to laugh at ourselves," says photographer Mahesh Shantaram.

Candid shots have their own charm. It's good if people aren't conscious of cameras and better if they can't even remember being shot. The photographer's own creative craft, of course, counts for a lot. "The most important thing is to establish a rapport with the bride and groom. Only once they feel comfortable will you get some unforgettable pictures," says award winning wedding photographer, Prakash Tilokani.

"Till six years back, no organised individual was involved in this craft. In the old days, only Mata Studios in Connaught Place, Delhi, used to do family portraits for really rich families," says Meher. It was then that she came across a young Badal Jain who looked at her collection of international

work, picked up the nuances, and hasn't looked back since. Whether it was Vikram Chatwal's marriage or the Mittal wedding, he got the contracts for them all. "And then there was Ronicka Kandhari, who wanted to do all the behind-the-scenes candid moments. I got her a break with Adish Oswal's wedding in 2004 and now she works with all the major wedding planners in the industry," adds Meher.

Technology has played a critical role in the transformation. Badal and his brother Raja, for instance, use 17 mega pixel cameras with flashes to shoot candid pictures. "We approach the event without intrusion, through complete absence of extra lights and cameras," says Badal. The upshot: gone are the days that brides and grooms had to garland one another in slow motion or repeat the action for cameras.

Photographic renditions are changing too. Shashikiran Kolar, for example, uses black and white on occasion to capture contrasting hues. With all this experimentation have come wedding albums printed as coffee table books. All the bulk is going away, replaced by classy layouts of specially selected photos. Weddings with 'Royal India' themes, for instance, are designed to reflect that. "The décor, trousseau and entry of the bride are some of the focal points of the coffee table book," says Kandhari.

The art isn't done changing yet. Rajnish feels that reality TV will dictate the evolution of wedding photography. "Liberal elements of drama, snide remarks, gossip, heartbreak and even patch-ups may be shown in the course of the marriage," he says. Meher, though, sees a migration to the Web as a platform, a la Facebook.

Emotion, however, will continue to rule. "It should not become like the Page 3 nonsense that happens these days. There are people in Europe who do only society pictures, but they are devastatingly strong pictures. I hope wedding photography doesn't go the same way," cautions veteran photographer Raghu Rai.