An Objective Portrait of Mumbai

THE BOMBAY PLAGUE of 1896, wrecked lives, but in one significant way, it also changed the city for the better. Shortly after the devastating bubonic epidemic caused more than 10 million deaths in British India, the Bombay City Improvement Trust was founded in 1898 during the tenure of William Mansfield, first Viscount Sandhurst (the governor of Bombay from 1895-1900). The trust catalysed efforts to upgrade sanitation standards in the colonial island that was getting congested at a frenetic pace. Lore has it that Lord Sandhurst laid the foundation stone of Bombay’s first chawl with a silver trowel whose inscription proudly announced that the ambitious project would be used for “housing the poorer and working class” migrants. With its intricate engraving, the trowel is an undeniable object of beauty and it also reveals itself to us as one of the last surviving symbols of the advent of urban development and modernisation in a city regarded as India’s financial capital today.

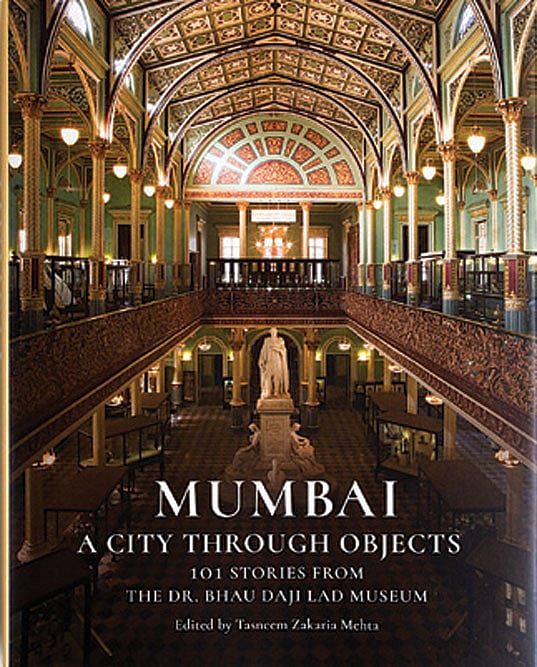

Nineteenth-century modernism is one of the riveting tales that flows from Mumbai: A City Through Objects: 101 Stories from the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum (HarperCollins; 372 pages;₹2,999). Profoundly entertaining and occasionally pedantic, Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum’s (BDLM) opus offers readers a glimpse into 101 stories from Mumbai’s history. Devised in the mould of Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects, the book has evolved from Tasneem Zakaria Mehta’s ongoing PhD research on colonial art institutions and is very much an attempt to decolonise the Raj-era patrimony. Mehta seems the perfect person to write this love letter to her city. “Even though I studied in New York and London and lived in New Delhi after I got married, Mumbai has remained a singularly great obsession of my life,” says the managing trustee, honorary director and face of the BDLM for over a decade. Mehta, who is the daughter of the late politician and educator Rafiq Zakaria, admits that she continues to be fascinated by old Bombay and its turn of the century history. She believes it was an age of adventure and discovery; “Bombay was truly a crucible of culture. Contrary to popular belief, Delhi was never at the forefront except during the Mughal period but lost its mojo as the action shifted to maritime Bombay, thanks to the opening of Suez Canal and the cotton boom. Kolkata was definitely a cultural powerhouse because of the Tagores and Santiniketan but Bombay was the most unusual because it had an intellectual energy and was also a thriving business hub, which was rare for an Indian city at the time. With this book, I really wanted to bring out Bombay’s storied heritage and its significance not just as a successful experiment in architecture, urbanism and economic development but also as a sociocultural force.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In a sense, Mumbai: A City Through Objects is a whittled down version of what you see at the museum. “Honestly, I would have liked to include every single object and artefact,” Mehta says laughing over green tea at her ground floor office in the BDLM premises one recent afternoon. “From planning to execution, the book just kept growing more and more extensive. We ended up having too much material on our hands though I am glad that the publishers were gracious enough to give us the space,” she says. All the main essays in the tome have been contributed by Mehta herself, with seven other writers and curators chipping in with shorter but equally pivotal entries. Formerly known as Victoria & Albert Museum, the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum was established in 1857. Built on a plot of land next to the botanical gardens in Byculla (a “salubrious and exclusive suburb” back then), the museum was a part of an Early Modern aesthetic movement that led to the “development of a public visual culture of collecting and displaying,” writes Mehta.

Considered India’s third oldest museum after Indian Museum in Kolkata and Government Museum, Chennai, BDLM commemorated its 150th year anniversary this May followed by the official launch of Mumbai: A City Through Objects. However, as Mehta points out, the BDLM building has the rare distinction of being the first museum structure to be built in India. An example of Renaissance Revival architectural style following Palladian principles and High Victorian interiors, the building’s construction took 14 years. “Architecture has always been used as an instrument for projecting power by the state, church or institutions. But like I always say, museums are the one place, which display people’s power,” Mehta quips. “For the British, museums were like cathedrals. These grand buildings were meant to showcase the finest human innovation and knowledge. But the Indian population failed to understand why they were so opulent, especially because they weren’t exactly temples or mosques. So, initially when the museums started opening in colonial India, they acquired popular local nicknames, like ‘Ajaaeb Ghar’ or ‘Jaadu Ghar’. People thought some jaadu tona was happening inside,” Mehta says laughing.

BDLM STARTED LIFE as an encyclopaedic museum with a strong focus on natural history. Mehta says that the British wanted to promote a scientific approach that would facilitate a better understanding of the exotic-sounding culture, customs and climate of the colonies. In the following decades, as the city of Bombay evolved into an industrial and economic destination the museum’s collection became more comprehensive to reflect the rapid changes. The book carefully singles out historic objects and curios associated with Bombay’s evolution, especially its “extraordinary industrial arts,” as Mehta puts it— the selection includes rare maps, Company-style paintings, photographs of streets and city views, dioramas depicting the life of the inhabitants of Bombay and the various tribes of craftsmen and workers, the famous ivory ‘Bombay boxwork,’ pottery, carpets and textiles, boats and harbours and even flora and fauna.

Greek geographer Ptolemy once called these seven idyllic islands Heptanesia while the Portuguese dubbed it Bom Baim, or the ‘good little bay’ and enjoyed a diet of homegrown rice and corn. The Heptanesia Relief Map (1700-1800) lays before the reader the cartographic display of Bombay prior to the British takeover from the Portuguese and after. It depicts the territory that the king of Portugal subsequently bequeathed to the British Crown towards dowry for the marriage of princess Catherine of Braganza to Charles II of England. Maps of Worli Estates similarly illustrate central Bombay before the proliferation of textile mills and after. A fascinating contrast emerges between what was originally a sparsely populated marshland and a developing settlement. As writer Himanshu Kadam notes in his essay on Worli Estates, “The first Indian cotton mill, the Bombay Spinning Mill, was set up in 1854 by Cowasji Nanabhai Davar. By 1890, there were seventy mills employing 59,139 workers.” The mill culture fostered a unique community life in Bombay, eventually becoming “an intrinsic part of the city’s identity,” Kadam adds. One of the earliest maps in the book is Fryer’s Map from 1672, a topographic study that highlights areas such as Bandura (Bandra), Canora Island (Kanheri) and Old Woman’s Island (Colaba) besides indicating the shallow reefs, settlements, vegetation and hills. There are also entries on the ivory trade that thrived in Bombay, which between 1870 and 1915 emerged as the third largest global market for ivory-related articles and a remarkable diorama that details Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s escape from the Mughal fort at Agra in a basket meant for sweets. One of the oldest stone sculptures in the museum comes from the nearby island of Elephanta. The aptly named Elephanta Elephant dates back to sixth century CE and is on permanent display at the museum’s entrance.

While the stated objective of Mumbai: A City Through Objects is to tell the story of Bombay through both the ornate works of art and humble artefacts created by unsung craftsmen practically lost in history, the authors are unable to resist the temptation to name-check the founding fathers of this metropolis by the Arabian Sea. Start with the obvious. The gentleman who lends his name to the museum, we learn, was a polymath and the first Indian sheriff of Bombay. Dr Bhau Daji Lad had migrated from Goa, moving to Bombay as a young boy. “It is believed that he found an early cure for leprosy,” writes Ruta Waghmare-Baptista in her essay. Ironically, the man who helped raise funds for the museum “lost his fortune in a stock market crash that followed the end of the American Civil War in 1865,” Waghmare-Baptista notes.

The book contains an interesting nugget about Juggannath Sunkersett’s (a rich trader and philanthropist) interest in farming. At the time, sugarcane was imported from Mauritius. “Today, Maharashtra is one of the largest sugar producers in the world and has its own sugar belt politics but few know that Sunkersett was among the first locals to have planted the sugarcane seeds in his farm. Only later on did it spread to the rest of Maharashtra. Sugarcane was never cultivated in India but thanks to Sunkersett’s efforts, we have a lucrative sugar industry,” Mehta says. Another of her favourite stories involve Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy and the Ice House of Bombay built in 1843. She says that the first ice cream in Bombay was made from ice imported from Massachusetts and the Ice House was opened to cater to the burgeoning demand. The illustrious man after whom Sir JJ School of Art is named had apparently pioneered the use of ice. “Sir Jamsetjee was famous for hosting lavish dinner parties and at one such gathering the guests were served ice. The next morning, the headlines in the paper read, ‘Guests catch cold at Sir Jamsetjee’s party after consuming ice,’” says Mehta.

She hopes that Mumbai: A City Through Objects will galvanise more Mumbaikars to look at their own city with whole new eyes: “Nobody will know these pieces of information about the city’s history unless they read the book or visit the museum. It’s our own slice of history that has gone into the making of modern India.” While the book is a cause enough for celebration she has a lot on her mind. Importantly, the museum has been closed for renovation since its roof was damaged after a heavy monsoon recently. Another immediate concern is the construction of an ambitious new wing, which she says has been in the making for many years. “We realised to fulfil its true potential the museum needs spaces for education and research as well as exhibitions. Look at the great museums of the world. We are tiny in comparison, yet our culture is so rich and we must do justice to that. I wish that politics will not intervene and we can build the extension, which will be a game-changer not only for Mumbai but for India.”