A Natural Artist

Atul Bhalla's new show continues his conversation with ecology and his lifelong meditation on water

A chair marooned in a plain of grass that could be in any country; a cloud of fire sighing over the same serene grassland; a man (the originator of this image, it turns out) hugging the ground and, it would seem, consecrating the ground that approaches crushing expanses of still- looking water. Most striking, a boat suspended surreally, between the sky and a river. The artist won't tell me how, but it doesn't, of course, matter; we could be anywhere, or nowhere. Where we are, however, is close to home: the beleaguered Yamuna.

"If you put a boat in the Yamuna, it won't flow; the water doesn't flow after Wazirabad. It goes in circles. People who see the work understood why I had created a boat that only goes in circles; because the water itself can't flow," says artist Atul Bhalla. "The environment has been a concern in my work, though I don't think of myself as an activist. I'm not a placard-holding, protest- in-the-street kind of guy. I like to consider how we as a culture perceive water from the point of view of art. On the riverbank, when we go to a restaurant, we ask, 'Ek bottle pani de doh !'" He laughs at the necessary ironies.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The piece is one of the most arresting in a series called Deliverance, showcased at his latest show, Ya Ki Kuchh Aur!, at the capital's Vadehra Art Gallery. In it, Bhalla displays photographic and video works created from 2012 on that include chiefly three projects: Inundation in Hamburg, Germany, Deliverance in New Delhi, India, and Contestation in Johannesburg, South Africa.

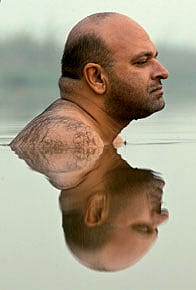

"Deliverance is part of a multiproject series I did, called The Wake. We have other works coming in," says Bhalla. "I engaged with traditional boatmakers; I found them north of Gorakhpur, to make this boat. The boat is now a permanent installation at the Heritage Transport Museum in Manesar. It hangs over the reception area, with a café underneath; you can actually think of the café as under water, as the boat is upstairs!" Bhalla spent 2013 working with the craftsmen to craft a boat with twin rudders, which birthed detailed documentation of the endangered culture and craft of the Mallah community. In Contestation, Bhalla used three months in Johannesburg at a residency in 2012 to focus on the large-scale privatisation of land and resources; thus the chair, placing humans very obviously within the context of their struggle with the land and with South Africa's power and racial politics. And in What will be my defeat?—II, part of the Inundation series, Bhalla uses the river Elbe to immerse the artist literally and metaphorically, as the river merges with the sea.

Single-minded artist of the aqueous, Bhalla continues to address the politics of water, in his dialectic with water wastage and consumption; he is part of a contemporary set of Indian artists who are engaging with modern sociopolitical issues in an immediate, accessible manner. Through video art, installations, sculpture, photographs and paintings, he has created a thoughtful and thought-provoking body of work over two decades. "Atul Bhalla's work engages with some of the most compelling urgencies of our time— water, and the ecological, historical and economic contexts of our relationship to water," says critic Ranjit Hoskote. "Bhalla, along with Ravi Agarwal, Arunkumar HG, Amar Kanwar, Sheba Chhachhi and a number of other artists, is at the forefront of a cultural inquiry into the war that humankind has unleashed on the natural world, as the only species committed to destroying rather than sustaining its habitat."

A marked cultural neutrality can be said to qualify much of Bhalla's work. It can also be surmised that this may have kept him from a larger role in the canon, but it has also brought him quiet, steady recognition: shows at the Aicon Gallery in London, the Sepia International in New York, the Institut Valencià d'Art Modern (IVAM) in Spain and the International Video Art Biennial in Israel, as well as many shows at home, at smaller institutions in Mumbai and Delhi's Triveni Kala Sangam and Lalit Kala Academy.

Bhalla's engagement with New Delhi and its water resources are significant, as he encourages viewers to look deeply at their context within urban spaces. Questioning the control, commodification and pollution of water, he has alchemised some of the most mundane debates around water, looking intensely at its physical, historical, spiritual and political relevance. Thus, a personal exploration turns public; a local context moves to the global stage. The bleak, almost autumnal quality of Inundation is typical of his kind of exploration; lone, rangy, understated.

A plain-speaking, no-nonsense kind of person, Bhalla is an unlikely artist, in the stereotypical sense of the word; when he speaks about his work, in clear, unsparing terms, it is with the precision of a tradesman. "I am not a camera-carrying kind of artist," he says. "I use a small digital camera. Something is staged, something has been done to it, but it is more than that."

"It all started out in 1998, when the public first invested in me. They realised what my medium meant to me," says Bhalla. He began with traditional painting and then moved to photography, that accessible yet enigmatic terrain of novices and masters. How was the transition? "From 2001 to 2004, I didn't do anything. This was the transition period. I did the first performative photo work then."

What is a photo performance? "It's me acting within an environment. People accuse me of not having people in my work; here, the attempt is to turn the camera on myself. I'm putting the gaze of the camera on myself. I'm turning the 'voyeuristic, violent' gaze of the camera on me. I'm shy, that's why I take pictures of myself."

Is this hiding, in one sense? "No, it's not a question of hiding, it's a question of losing yourself."

Bhalla's works (which he may spend two years on individually) often begin with literature, as much as they do with life. "In Shanghai, I was listening to water, crouching in the middle of the street. You Always Step in the Same River is the title of that show. The idea is that if I'm stepping in the Yamuna, I'm also stepping into the same river that runs in China. And, I was using the work of Jung Chang." He uses the terms 'red' and 'black', used to refer to Communists and non-Communists, as he details his involvement with the great narratives of China's revolutions and identity authored by Chang, among them her family autobiography Wild Swans and a biography of Mao Zedong. Everything is connected, of course, like the universal water body. "After the Cultural Revolution, a lot of names changed; just like in Delhi where you have Dhaula Kuan, Hauz Khas, Khari Baoli—where is the kuan, khas, baoli?"

A member of KHOJ International Artists' Association, Bhalla works from a studio in Janakpuri, and now teaches three days a week at Ashoka University, which has just started its first Master's degree in Art. "I've been teaching a long time," he says. "I was teaching high school for 17 years before the art boom; nothing sold then." The big sales came at last, and now, at a pivotal point in a slow-burning career, Bhalla is showing in New York in March and talking at New York University and several other universities.

"My work is in the documentary mode but it is not a documentary itself. Be it the boatmaking or me carrying a chair around an African landscape, these are very corporeal experiences for me," says Bhalla. "I need to be there doing it, sometimes again and again. You keep going on in what you do. A lot of people miss out on this journey in art. The work is also about craft, material, and all of this becomes part of the journey that you're on."

(Ya Ki Kuchh Aur! is on view at the Vadehra Art Gallery, Defence Colony, New Delhi, until 20 December 2014)