A Burning Question

Mumbai's Parsis find themselves divided over a crematorium for those who'd rather not opt for the traditional Towers of Silence

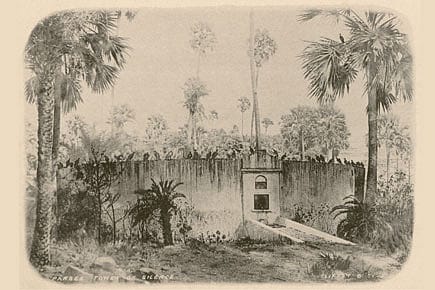

When Dinshaw Tamboly was about eight years old, he attended a Parsi funeral for the first time. His grandfather had passed away and his body was taken to Doongerwadi, Mumbai's Towers of Silence, as the community's traditional funeral site is known. Tamboly remembers entering this lush green area in Malabar Hills with the funeral entourage for the first time, before the corpse-bearers took the body away to the dakhmas, or wells. He recalls looking at the sky and seeing a ring of vultures flying in gleeful anticipation. Someone told the young Tamboly, pointing at the vultures, "The body will be over in half an hour." Once the flesh was consumed and the bones bleached by the sun, in accordance with tradition, the skeletal remains would be pushed into the well's central pit. Back then, all this only took a few days.

As the years went by, Tamboly says, he never gave much thought to this ancient tradition of disposing of the dead. In this day and age, the thought of feeding the lifeless remains of people to vultures might strike some as macabre, but to Tamboly, like other Parsis, it was their way. Sometime in the late 1990s, when Tamboly became a trustee of the Bombay Parsi Panchayat (BPP), the trust that governs Doongerwadi, he learnt that some people living nearby complained of a foul smell from the Towers. "They said they couldn't bear to keep their windows open," Tamboly recalls.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

As a trustee, Tamboly had been given charge of the upkeep of the area, a 54-acre patch of land on the eastern slope of uptown Malabar Hills that is often described as a mini-forest. Despite the rule that no one but corpse-bearers can visit the three wells where cadavers are left for vultures, Tamboly visited them to investigate the matter. "What I saw was horrible," he says. "There were piles of hundreds of corpses in different stages of decomposition, rotting in the open. When I looked around, there was not a single vulture around," he says. Asked, the corpse-bearers there told him that rather few vultures ever descended to the wells, leaving corpses uneaten for long periods of time. Other avian visitors such as crows and kites would sometimes fly off with and drop pieces of flesh on the terraces of nearby houses and balconies of buildings.

Tamboly asked other trustees to visit the spot to impress upon them the need to find a solution. "But very soon," he says, "all of us realised that the entire system had collapsed." As information of rotting corpses became common knowledge, he realised that many Parsis were increasingly turning to cremation. In response, he urged other BPP trustees to build an electric crematorium within Doongerwadi, and if not, at least allow the families of those who had been cremated to pray for their souls in the community's prayer halls. "But the high priests forbade any of that. They said cremation was sacrilegious and couldn't be permitted. Neither was a crematorium allowed nor the prayer halls opened to all," he says. "They said the soul of the cremated would be lost forever."

The issue has created a deep rift within the community. Zoroastrian high priests have strictly forbidden cremation and burial, branding all those who choose or advocate these as 'renegades'; fire and earth are holy under the tenets of the faith and are not to be defiled.

Those who advise cremation, however, say the traditional method of disposal has failed, and so a pragmatic option is needed. They complain that the high priests have not only prohibited cremation, they have barred priests from performing funeral prayers for those who are cremated. According to Zoroas- trianism, four days of prayers must be held after a family member dies. It is believed that this helps the soul reach and cross a mythical chinvat bridge that lies between the two worlds of the living and the dead.

Since the high priests would not hear of cremations and the BPP was reluctant to allow them space, about two years ago, Tamboly and some like-minded Parsis started negotiating with Mumbai's municipal authorities to let them build a prayer hall for cremated Parsis. Last year, Tamboly formed the Prayer Hall Trust, and a few weeks ago, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corp allotted them space in a public crematorium complex in Worli to set up a prayer hall for all faiths. This hall is expected to cost about Rs 1.7 crore and will be ready in 15 months. The trust will employ priests to conduct prayers for those who opt for cremation. And while use of the hall will be open to all faiths, Parsis will be given preference at certain hours. The hall will also be open to those Parsis who marry outside the community and for their children, another contentious issue among Parsis, since the high priests do not consider children Zoroastrian unless both parents are by birth. "I don't think the traditional-minded will be too happy," says Tamboly.

India once had one of the world's largest vulture populations. The country has one of the planet's largest livestock populations; cattle slaughter is forbidden in most parts. For a long time, this helped the birds thrive. However, with the painkiller diclofenac being put to extensive use on cattle across the country, vultures began dying in huge numbers of poisoning. The drug, it was found, causes kidney failure among birds that feed on corpses treated with it. The veterinarian use of diclofenac has been banned in India but its use remains widespread. The BPP's efforts to have doctors not prescribe the drug for Parsi patients, Tamboly says, was not successful either.

With a drastic fall in India's vulture population over the years, the Parsi community has been searching for solutions. At one point, the BPP approved a part- herbal, part-chemical substance to hasten the decomposition of bodies. "The composition had to be poured into the orifices of the dead. It also led to sludge within the wells, where corpse-bearers often slipped," recalls Tamboly, "It wasn't pleasant at all and we had to stop it." Later the BPP started using large solar reflectors to dehydrate bodies in the wells, a system which is still in use, before the remains are buried en masse within the area. Since each adult body takes at least about five days to dehydrate, concentrated mixtures of flowers are kept in a number of pots and ozone gas is frequently released to mask the stench.

Efforts to retain the classic funeral tradition have seen other forms of innovation, too. The BPP once flew down an expert in birds of prey from the UK, Jemina Perry-Jones, to help establish an aviary for vultures in the Doongerwadi area. The plan was scrapped because the BPP felt the expense of such a project would be too high. Some years ago, the captive-vulture plan was revived and help sought from the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) to set up an aviary within the Sanjay Gandhi National Park on the outskirts of the city (and a 'satellite' aviary within Doongerwadi). Under the plan, by January 2014, vultures were supposed to be at full strength again, leaving no flesh on corpses placed in the wells. While Homi Khusrokhan, director of the BNHS, claims that the Society is still in talks with the BPP over the project, Muncherji Cama, a BPP trustee, says the idea has been shelved for the time being.

Parsis who advocate alternate methods of disposing of the dead claim that Zoroastrian high priests ostracise and look down upon them for their beliefs. In 2009, the BPP, supported by the high priests—in a move construed by reformists as an attempt to warn them— banned two reformist priests from entering not just Doongerwadi, but also fire temples.

High priests have been held in high esteem down the centuries since Parsis migrated to India's West coast from Persia. They are involved in such rites of passage as Navjote initiation and marriage ceremonies. Those among the priests who have been welcoming non-Parsis into the community fold—say, by allowing children of mixed couples Navjote ceremonies— and performing prayers for the buried and cremated have been shunned by the traditionalists. Reformist priests, cast out for their alleged sacrilege, took the matter to the High Court, which ruled in their favour, but the BPP has appealed to the Supreme Court. The apex court has appointed a mediator between the two parties but no breakthrough has been achieved yet. The two parties refuse to speak on the matter since the case is still in court.

While well-to-do Parsis rarely have difficulty employing priests to perform prayers for their dead, regardless of the method of disposal, the less affluent are in no position to rub the high priests the wrong way. "Many Parsis are willing to go against current beliefs and opt for cremation," says Homi Dalal, a 69-year- old activist, "But they do not want to risk not having the final prayers done." Now with a prayer hall that is open even to those cremated, he says, more Parsis will opt for cremation. According to Tamboly, around 750-800 bodies are brought every year to Doogerwadi. In comparison, some four or five choose cremation. According to a December 2013 survey by Parsiana, a community newspaper, 28 per cent of all respondents said they wanted to be cremated over the traditional method.

Dastur Mirza, a Zoroastrian high priest, is furious about that prayer hall. "These people, the priests who work with them, they are all renegades," he says over the phone, "Have they studied Zoroastrianism? Who are they to start a prayer hall?" With that, he disconnects the call in anger, only to call back later, asking me not to malign the community.

Meanwhile, the BPP's Cama reckons that the current system is efficient enough, if not perfect. "Yes, there are no vultures. But Zoroastrianism never [places emphasis] on those birds, but the sun. And with the help of solar panels, it is working well enough."

In 2006, a Parsi woman named Dhan Baria sneaked into Doongerwadi along with a photographer she refuses to name. A few months earlier, after her mother's death, her body had been taken there. When she inquired a few days later, a corpse-bearer apparently told her about how bodies end up rotting in the open. The duo—Baria and the photographer— took 108 pictures of corpses rotting in the wells. According to her, she approached the BPP with these pictures, asking them to set up a crematorium or burial space within Doongerwadi. When they refused, she distributed the pictures within the community.

The photographs stunned Parsis across the world. Dalal remembers how his wife, who had often rebuked him for his 'reformist' views, declared in response that she preferred to be cremated instead.

Baria claims that the BPP tried to ignore the outrage by questioning her faith and calling the pictures fake. Since then, Baria has set up the Nargisbanu Darabsha Baria Foundation, named after her mother, to help underprivileged children and HIV patients. "But even after all these years," she says, "I can't help but think when I took those pictures [that] my mother's body was probably lying in that pile of rotting corpses."