5G: Future Continuous

The official launch of 5G in India brings with it an economic boon and a regulatory challenge

Anil Padmanabhan

Anil Padmanabhan

Anil Padmanabhan

Anil Padmanabhan

|

07 Oct, 2022

|

07 Oct, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/FutureContinuous1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

DEEPAUL’S COFFEE, A small shop, is located on the ground floor of Janpath Bhawan at Connaught Place in New Delhi. Today, it is an also-ran beverage stall. But in the 1980s and 1990s, it was an iconic hangout place where the youth could lounge about sipping cold coffee and fantasise about life. There was one catch though. The rendezvous with friends had to be fixed earlier. Mind you, this was in the era when even landlines were few; the idea of cellular phones was not even on the horizon. However, some enterprising youth had figured out a jugaad. They would scribble cryptic messages for buddies on pamphlets posted on the notice board.

Fast forward three decades to October 1 when India formally embraced 5G telephony—the moment which, among other things, launched the era of the Internet of Things (IoT). Theoretically, this has provided the power to rewire the notice board to actually communicate with individual users.

Now, scale this example to every aspect of economic activity and the scope of 5G in India is all apparent. This ability of machines to talk to each other presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for India to overcome its legacy handicaps and leapfrog into the next stage of growth—wherein the spoils are shared and not limited to the elite.

India’s unique digital commons, through public digital goods like Aadhaar and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), have already demonstrated this capability. Whereas 10 years ago 430 million people did not own a bank account, today they can potentially leverage their data to access personal loans. If financial inclusion, which, given the existing momentum, would have taken another 40 years to achieve, was pulled off in six years, then the disruption in payments forced by UPI was something else altogether. Starting from just a million transactions in 2016, UPI is now logging just under seven billion transactions a month—50 per cent of which are for sums less than ₹200. It is projected that these transactions will scale to one billion a day.

The launch of 5G, therefore, is as Prime Minister Narendra Modi said at the inauguration: a “historic moment”. “5G is a knock on the doors of a new era in the country. 5G is the beginning of an infinite sky of opportunities,” Modi added.

THE OPPORTUNITY

The simplest explanation of 5G is that it is 4G on steroids. While not off the mark, it tends to shrink the capability of this powerful technology upgrade to a single dimension.

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the scale of promise of the 5G-powered global economy is staggering:

“Fast, intelligent Internet connectivity enabled by 5G technology is expected to create approximately $3.6 trillion in economic output and 22.3 million jobs by 2035 in the global 5G value chain alone.

“This will translate into global economic value across industries of $13.2 trillion, with manufacturing representing over a third of that output; information and communications, wholesale and retail, public services and construction will account for another third combined.”

Similarly, a recent study undertaken by Deloitte for the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), the trade body, captures the potential of 5G for India:

– Data speed in 5G is expected to be around 10 Gbps (compared to existing speeds of 20-40 Mbps). Not only will it dramatically improve user experience, it will also revolutionise mobile content;

– 5G network is being designed for less than 1 millisecond latency (or lag). Hence, in conjunction with IoT it will be the key technology choice in industries like automotive, medicine, manufacturing;

– 5G technology will move the processing ability of handsets to mobile edge/cloud, ensuring longer battery life;

– 5G in a Software-Defined Networking (SDN)/Network Function Virtualisation (NFV) environment will enable customised service delivery;

– 5G is expected to use higher frequency bands (30-300 GHz) which will provide better capacity, bandwidth scalability and lesser interference.

According to the study, the rollout of 5G could spur the growth of India’s digital economy to $1 trillion—which is about a third of the size of the current gross domestic product (GDP) of India.

THE ECOSYSTEM

Historically, India has a consistent precedent of missing such opportunities. The most recent being its inability to ride the unprecedented global growth boom in the first decade of the millennium. Yes, it did well. But it could have been so much more dramatic; similar to the spectacular surge managed by China.

The single biggest stumbling block has been the lack of an enabling ecosystem and political will. The good news is that India’s unique digital commons have spawned a digital architecture that is inspiring unprecedented inclusion, especially by enabling the power of disintermediation. It is successfully cutting through decades of sloth, red tape and corruption to carve out an enviable swathe. It is only a beginning, yet very symbolic indeed.

The rollout of 5G could spur the growth of India’s digital economy to $1 trillion, about a third of the size of the current GDP of India. It opens up possibilities, as a standalone offering and combined with other services

This power was first demonstrated in the 1990s with the introduction of the automated teller machines (ATMs). It eschewed the painstaking and time-consuming red tape that a customer had to endure to draw or deposit money. Thereafter, the government initiated baby steps to expand this idea, but never enough to tilt the scales in the fight against red tape.

The tipping point was initiated in 2009 with the launch of Aadhaar, the unique 12-digit identity issued to everyone residing in India. It was also India’s first digital public good (DPG) as it was based on an open digital architecture, which is nothing but public digital rails that allow anyone, government or private, to build applications on top. It laid the foundation of one of the most profound socio-economic transformations of India.

This process got a big leg-up with the launch of UPI which combined the identity and consent layer to create probably the most powerful disruption in real-time payments business worldwide.

Prior to UPI, which was launched by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), digital wallets existed. However, they operated like walled gardens with users captive to one single network and unable to commercially interact with those using rival wallets. What UPI did was make the wallets interoperable. Not only did it realign the competition metric to innovation but it also expanded the payments pie many times over.

Very soon, each of these DPGs, which had already evolved as independent vectors, could be combined to create even more powerful digital assets. UPI was among the first such examples.

Later, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which took office in 2014, decided to employ this as a tool of financial inclusion. It created the idea of Jan Dhan (no frills bank accounts), using Aadhaar as the means of eKYC (Know Your Customer) to enable financial inclusion, thus monetising an individual’s identity.

Subsequently, Jan Dhan was combined with Aadhaar and an individual’s mobile to create JAM. It provided an economic GPS making it easier for government to locate and target a beneficiary of social welfare. An obvious spin-off in this Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) was that it prevented leakages (cumulative savings to the exchequer so far are estimated at ₹2 lakh crore).

Also, there is one common utility binding DBT, UPI and even FASTag (the machine-readable pass that enables seamless payment of toll for motor vehicles). All of these assure frictionless transactions.

In the last decade, India’s unique digital commons have weaponised the disintermediation using transparent and powerful digital tools and made transactions frictionless, providing social ballast to propel unprecedented socio-economic empowerment.

GOOD OPTICS

While the gains have been impressive, the expansion of India’s digital economy is beginning to get cramped by the digital divide. There is a big risk that Bharat would be left out of this play. The intent was there but previous governments had failed to do the heavy lifting to connect all of India on a robust digital highway.

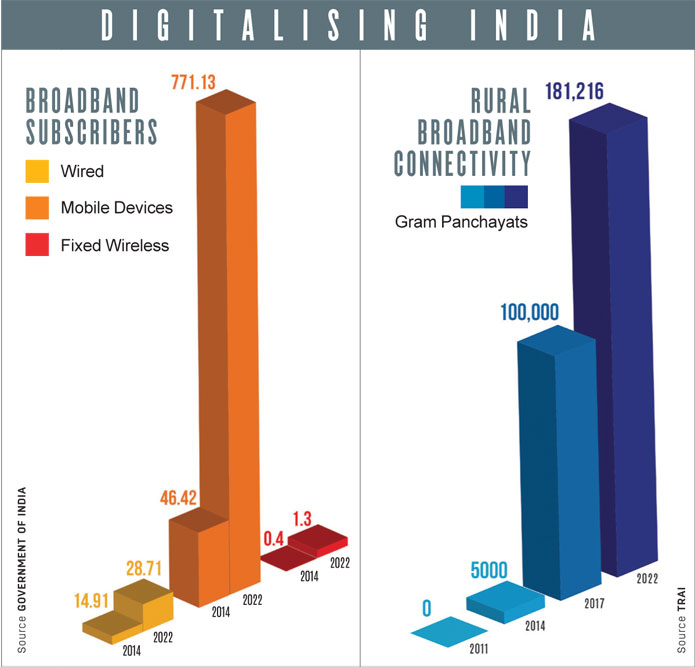

The National Optical Fibre Network (NOFN) to enable broadband connectivity to rural India was birthed on October 25, 2011 under the leadership of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA).

Unfortunately, the otherwise brilliant idea was dead on arrival. In the three years after launch, only 5,000 gram panchayats were brought on the optic al fibre grid. Worse, villagers failed to derive the benefit of their village being on the broadband grid.

A post-mortem by a high-level committee in 2015 uncovered the structural flaws in the existing plan:

– Last-mile connectivity to households was not part of the initial ask;

– WiFi hotspots had to be generated in villages;

– State governments were not stakeholders;

– Right of way issues disrupted laying of cables.

The Union government, which by now was NDA, acted on these recommendations. The pace did pick up (see graphic), but nowhere near the desired levels. Part of the reason was the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. So far, of the 2,62,825 gram panchayats in the country, 1,81,216 are now part of the optical fibre network (as of July 1).

The good news is that there is a definite acceleration in the rollout of the fibre network. But the bad news is that the project is way behind schedule. Hopefully, if the current pace is sustained, then all of rural India should be on the optic fibre grid in the next two years. The big takeaway is that the enabling ecosystem is gradually falling in place. And in this, one key ingredient, political will, is very visible.

THE HARVEST

Officially, 5G has already been rolled out by Airtel. And Reliance Jio has promised its service by Diwali. Effectively, it is a commitment to make 5G available nationwide.

However, this rollout is likely to be calibrated, favouring enterprise users over consumers in the initial phase. Frankly, there is nothing wrong with this, especially given the fact that the power 5G accords to enterprise users is staggering.

Take, for instance, healthcare. 5G with its high-speed digital highways will make it possible to undertake remote surgery by enabling the real-time monitoring of a patient’s condition.

At present, this ability is limited. What 5G is offering is data speeds of unimaginable orders of magnitude, split-second response times, and connecting all kinds of IoT devices. In other words, if 3G and 4G were about connecting humans, 5G will expand the functional set of telecom to connect devices. Therefore, a new feature of functionality that we will see is the ability to process huge amounts of data, which, for instance, is very, very useful and critical in Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications where you try to infer useful information from huge datasets. At present, these are difficult to pull off as enterprises neither have data-processing capacity nor do they possess requisite data speeds. The sectors likely to gain most immediately are entertainment, logistics, health, education, manufacturing and gaming, all of which require very large processing capacity.

The ease of deployment of AI in a 5G environment will also give a fillip to India’s audacious plan, Bhashini, to democratise the use of the internet by allowing access to it in regional languages. Officially, India recognises 22 languages with 12 scripts and translation of content at this level of diversity and scale is simply impossible without the use of AI.

Similarly, 5G and the associated ecosystem of IoT open up immense possibilities in their deployment in agriculture. For instance, the growing frequency of extreme weather incidents suggests that the current use of natural resources, especially water, will come in for more restrictions in future. The emphasis will be on optimising the inputs and in this IoT can be deployed to manage, say, drip irrigation, to monitor soil exposure to chemicals and fertilisers, or to set up smart greenhouses.

An additional facet of 5G is the ability of the technology to enable customisation of services by slicing and dicing the telecom network. Existing technology binds everyone alike; one size fits all. But under 5G, operators like Airtel and Reliance Jio will be available to offer a private network restricted to either, say, a university campus, factory floor, hospital, or some specialised administrative set-up in the field.

Finally, the business of communication is being turned on its head. Where initially the focus was on a linear delivery of services through landlines and later cellular, the scale and innovation of communication technology has made it possible to now use other mediums of communication like satellites.

The latter is especially true after the launch of LEO, or low Earth orbit, satellites which circle the Earth in as little as two hours at a height of about 2,000 km. Among other things, this has made it possible to provide internet connectivity to topographically challenged habitats and locations. As a result, a provider can mix and match telecom and satellite services to offer customised packages to clients.

Indeed, 5G opens up immense possibilities for India, both as a standalone offering and when combined with other services. At the same time, it also poses a challenge to regulation. The existing regulatory framework is not sensitised sufficiently to convergence of technology, such as between telecom and satellite offerings. How India deals with this curveball will influence its ability to harvest the promise of 5G.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

The lament of a blue-suited social media platform Chindu Sreedharan

Pixxel launches India’s first private commercial satellite constellation V Shoba

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita