Sagas from Solapur

How an online self-publishing portal turned small-town housewives into authors with a mass following

Aditya Mani Jha

Aditya Mani Jha

Aditya Mani Jha

Aditya Mani Jha

|

09 Dec, 2024

|

09 Dec, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Book-Art-scaled.jpg)

(Photo: Alamy)

Whenever a newspaper completes a certain temporal landmark, observers tend to focus on metrics like the total number of subscribers, number of households reached in big cities and so on. Today, for an app-based service like Pratilipi (which completed ten years recently), the crucial metrics are slightly different. 26,000 active writers contributing stories monthly for a reader base of 26 lakh people, across several Indian languages, a total of 14 million stories so far. But the one metric that really catches the eye is this: the average Pratilipi user reads for an average of 75 minutes daily. In today’s attention-deficit era this is an impressively high share of the reader’s day. “In our case, we have always had a ‘freemium’ model so it was always one of the most important metrics for us,” said Pratilipi co-founder and CEO Ranjeet Pratap Singh. “It was about striking a balance between keeping readers coming back for more and keeping writers happy, so they keep producing popular content. For that to happen, we had to ensure that the monetisation process worked for our writers, that the process was smooth and easy. But the motto has always been ‘retention first, monetisation later.’”

One of the big draws of an online platform is that it allows budding writers to bypass the traditional publishing industry, widely perceived as opaque and inaccessible. It’s also a low-fuss way to test the waters. While talking to a group of women Pratilipi writers from across the country, it became clear that this new mode of reading, writing and publishing offered certain obvious lessons for everybody involved in these realms. These are new writers who developed an organic following from scratch on the app and are now capitalising on their hard-fought fanbases. Their journeys offer unique lessons into the rapidly shifting ways in which we disseminate and consume literature.

Take Vaishali Manthalkar for example. This 36-year-old housewife living in Solapur district, Maharashtra, began writing stories on the app in 2019. “I had always loved reading stories,” Manthalkar said during a telephonic interview. “Around six-seven years ago, I was in a phase where I was reading a lot in Marathi. And one day I felt like I too could write a ‘paarivaarik’ story.”

The ‘paarivarik’ (family-centric) bit would become a signature for Manthalkar who now has over 60,000 followers on Pratilipi. Her serialised Marathi story ‘Reshmi Naate’ regularly clocks lakhs of views with every new instalment. The narrative begins with the story of a ‘contract marriage’—a practice deployed in Maharashtra usually by young women seeking to get visas. But it soon settles down into the familiar rhythms of the good ol’ soap opera—fathers and sons, mother-in-law and daughters-in-law chafing against each other’s likes and dislikes.

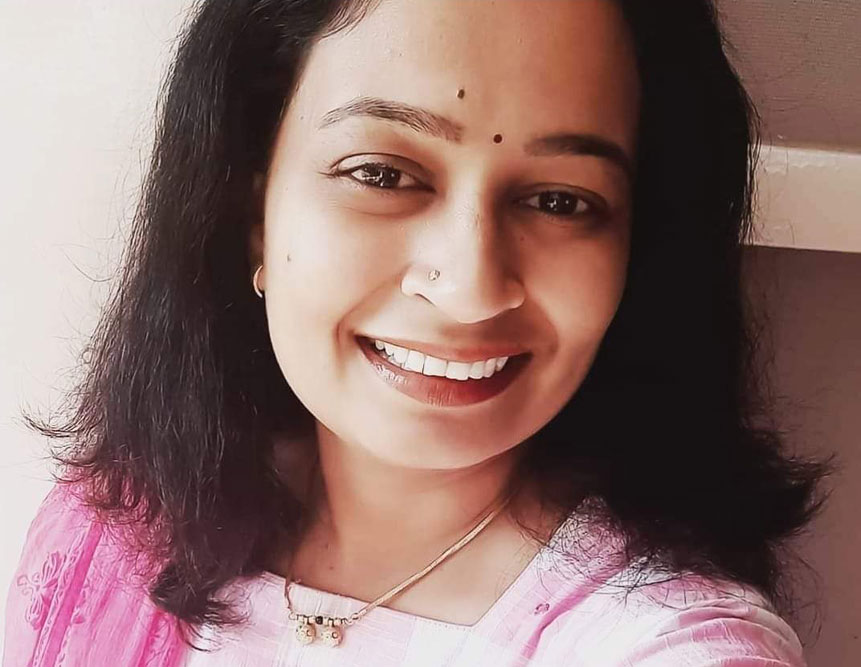

“In my stories the characters are generally ordinary people, who you would meet in everyday life. I think this is why readers find it easy to place themselves in those scenarios,” says Kirti Jadhav, author

“I feel like in today’s cinema there is usually a lot of violence and bloodshed,” Manthalkar said. “But there’s not that much family-oriented content, and I think this is one of the reasons why people connect with my stories.” Where one part of the market falls short, another quickly steps into the void, such is the way of the new digital media landscape.

A turning point for many online writers—and readers—came during the latter half of 2021, while the second wave of the Covid-19 epidemic was sweeping through the country. Many, like 39-year-old Kirti Jadhav, found themselves turning to reading and writing as a coping mechanism. “My husband fell ill with the coronavirus during the second wave,” Jadhav said during a telephonic interview. “My own mental health was not very good during that time. I was very anxious and my doctor advised me to focus on things I loved. I started reading a lot of Marathi stories on the Pratilipi app and one day I created an account and decided to write my own stories.” Today, Jadhav (who writes under her maiden name) has over 50,000 followers who read her serialised love stories like ‘Albela Sajan’ and ‘Tujha Rang Laagla’. “Romance was always a popular genre on the app, I noticed,” Jadhav said. “In my stories the characters are generally ordinary people, who you would meet in everyday life. I think this is why readers find it easy to place themselves in those scenarios.”

It is heartening to see early-career practitioners like Jadhav and Manthalkar earning upwards of Rs 1 lakh per month via their fanbases. For both housewives, this is the most money they’ve ever made. Indeed, Jadhav who lives in a village near Pune confirmed that for the 18 years of her marriage she had never even considered working for a living outside her in-laws’ house. Beyond the first-degree sociological implications, there is also the more immediate, pragmatic matter of ‘publishing economics’. On the Pratilipi app, users have the option of supporting individual writers instead of subscribing to the entire platform. The overall premium package is Rs 150 per month but the individual writer-only subscription is just Rs 25, thereby incentivising the building of fan-communities (there are also redeemable digital ‘coins’ that readers can send to their favourite writers, regardless of whether they are followers). And communities are another crucial part of the puzzle for online writers. “Reader feedback is very important,” Manthalkar said. “People have often written to me when I am mid-way through a multi-part story, and it has helped me in terms of providing a satisfactory resolution to the plot. You have to maintain your originality while also giving people what they want.”

“It was about striking a balance between keeping readers coming back for more and keeping writers happy, so they keep producing popular content. For that to happen, we had to ensure that the monetisation process worked for our writers, that the process was smooth and easy. But the motto has always been ‘retention first, monetisation later’,” says Ranjeet Pratap Singh, Pratilipi co-founder and CEO

That last line from Manthalkar points towards a broad similarity between these online communities and more traditional modes and marketplaces for reading/writing. Avid readers spot patterns in the market output and seek to ‘correct’ perceived deficiencies. Aparachitha (a feminised form of ‘anonymous’) from Kerala began writing Malayalam stories under this pen-name in 2020. “When I began reading a lot of short stories on Facebook, I thought some of them were really good but others were written with too much decorative language,” Aparachitha said during an interview. “I had always been drawn more to literature which used simple language so I started writing dramas in that vein, which I thought would resonate with the common man.” According to Naiyamika, another pseudonymous writer from Kerala, the largest chunk of returning readers do so because “something in the story reminds them of themselves, but also offers something new, a fantasy.”

“I can get the reader to click on my story with an attractive image,” she said. “To get them to stay or to return tomorrow I have to offer something in the story for all kinds of readers. When I write, though, I imagine a reader very much like me, who shares my interests and my dreams and fears.”

It is fascinating to see the connections between these online stories—and the turbo-charged, rapidly changing media sandbox they are playing in. In terms of both form and content, the stories are responding to what they see as the reigning cultural trends of the day. To that end, the thumbnail images for so many stories on the Pratilipi app featured movie stars—I counted people from the Hindi, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam-language industries. For obvious reasons, rugged-looking bearded men like ‘Rocking Star’ Yash, Allu Arjun et al dominate. But popular/mainstream cinema, as is clear by the evidence of these last 10-15 years, barely seems interested in telling women’s stories anymore. So, the likes of Manthalkar, Naiyamika et al are doing their best to fill in.

“I feel like in today’s cinema there is usually a lot of violence and bloodshed. But there’s not that much family-oriented content, and I think this is one of the reasons why people connect with my stories,” says Vaishali Manthalkar, author

The success of these women is also indicative of another market-void that has opened in the last 10-15 years: the gradual decline of print magazines (in Hindi, Telugu, Marathi et al) aimed at a female readership. When I was growing up in Ranchi in the late 1990s, there was a thriving culture of cheaply produced Hindi print magazines. And the same sense of community that readers and writers are striving for at Pratilipi was accomplished by magazine clubs, society-level lenders who would rotate magazines through a whole residential colony of housewives. A lot of these magazines (Sarita, Grihashobha, Manorama etc) had permanent sections devoted to reader-submitted fiction and ‘life experiences’. These are paradigms of reading and writing that have been rendered all but obsolete even in smaller towns across India, because of a combination of economic factors.

What lessons, then, may these homegrown success stories offer to the traditional, brick-and-mortar publishing firms of India, especially English-language ones? After all, this is an industry that has struggled to introduce new superstars. Increasingly, their successes have depended more on cashing in on big-name authors than blooding new talent or taking creative leaps of faith. According to Ranjeet Pratap Singh, writers and creators need to adapt to the realities of the post-social media era.

“You should be investing your time developing a personal relationship with your readers. Just keep them engaged—this was the biggest lesson that we learned during our early days 10 years ago. The other piece of advice for young creators is simply: write something every day, publish every day, learn from reader feedback. Figure out what you offer to the readers that’s uniquely you.”

This is pragmatic advice that’s currently working wonders for the likes of Naiyamika, Manthalkar and co. Pratilipi is poised to pay out Rs 2 crore in author royalties in December (after hitting the 1.5 crore mark in August) —and this is not counting their traditional publishing wing, Westland Books which they acquired in 2022, just a year after their acquisition of IVM Podcasts. And while there is likely to be some overlap between their respective clienteles, Singh sees no clash between these various storytelling wings of his business. “Our philosophy has always been simple in this regard,” Singh said. “If there’s a podcast that’s resonating with the readers, why not bring out a book based on it? If there’s a book that has sold a large number of copies, why not serialise the story in the audio format? A good story is a good story regardless of the medium, this is what we’ve always encouraged and what we continue to believe in.”

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

Bapsi Sidhwa (1938-2024): The Cross-border Author Nandini Nair

MT Vasudevan Nair (1933-2024): Kerala’s Goethe Ullekh NP

Inside the Up and Down World of Yo Yo Honey Singh Kaveree Bamzai