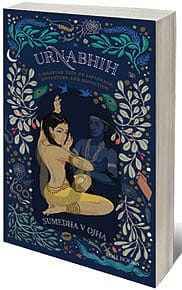

Love, Sex and Satraps

A courtesan-turned-spy frolics in Pataliputra, revealing Mauryan mischief

As the explanatory sub-title of Urnabhih states, Sumedha V Ojha's story of palace intrigue and military conspiracy is set in the 4th century BCE, at the dawn of the Mauryan period, with a young Chandragupta doing whatever it takes to establish an empire in the northern regions of the Subcontinent. The protagonist of this tale, littered as it is with handsome, virile and skilled warriors, is a dancer. More correctly, she is that fabled creature, a ganika, a highly sophisticated courtesan of ancient times, fit to share the company of noblemen and kings. She is their equal in terms of refinement and intellectual training, but often, she surpasses them in native cunning and the instinct to survive.

Our ganika, Misrakesi, comes to Magadha from Ujjain to avenge the death of her equally gorgeous and skilled sister. But before she can make her killer move, she is persuaded by the 'Acharya' (no prizes for guessing who that might be) to become part of the Urnabhih, his spider- web-like network of spies that lurk within the newly usurped kingdom as well as outside it.

Misrakesi embarks on a journey that takes her from the sheltered Apsara Sabha that she creates for the entertainment of Magadha's finest to the kingdom of Kaikeya, teetering on the brink of chaos as its aged monarch lies dying. Along the way, she falls in love and has a lot of earth-shaking sex but she manages to ensure that the Acharya's complex plans—to elevate the charismatic goatherd Chandragupta to Samrat of Jambudweepa—bear ripe and abundant fruit.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

Ojha has a fluency and ease with the historical material that she manipulates in order to tell this rollicking tale. The Greeks, like the overthrown Nandas, hover in the background, not yet a spent force. The Sungas have been assimilated into the new administration by the young Maurya, ably advised by Chanakya. The formidable empire with its base of loyal satraps has yet to cohere around a single, undisputed monarch—all this is part of the fourth century history we know. Ojha's solid research, the exuberance of her writing and her clear passion for the period allow her to animate and actually render clear this period of murky turbulence, churned as it was by many contenders for power. She does this by creating believable (if excessively heroic) characters set against a backdrop of entirely plausible conspiracies and intrigues.

The fact that we see this male world through the eyes of a woman is, for me, a compelling narrative strategy. Choosing the courtesan, the woman who belongs to no one, who is simultaneously inside and outside social structures, is a master stroke. Misrakesi can have the courage and the adventures of a warrior, the contrivances and intelligence of an advisor and the ambition of a courtier on the rise, but as a ganika, she remains eternally seductive, eternally ambiguous, all things to all people at all times.

Ojha's author's note tells us she was born in Patna and therefore, she returns to her roots to tell us a story set in Pataliputra—the jewel of the East, a thriving and conniving metropolis in a sea of less alluring urban settlements. Further, she says that she has a 'cherished dream of writing to bring the beauty and nuances of ancient India before the world'.

I'm not sure that Ojha is on her way to mission accomplished when early on, she writes such sentences as: 'The date of the marriage has been fixed for one month from today, during the shuklapaksha, on the auspicious muhurat of the Shiva-Parvati vivaha'. Even by Ojha's liberal reckoning, in a book that she sprinkles with Sanskrit words, a single sentence like this one requires two glossary entries. Nonetheless, Ojha has a good story to tell and she tells it well.

Prominent on the back cover of the book is a box that tells us that the book is 'soon to be a major TV production.' That's right, ladies and gentlemen, this story is headed straight for the small screen—and there's already a sequel in the works. From your favourite chair, in your own living room, you can look forward to bevies of bejewelled ladies, battalions of topless men and a multitude of opulent palaces as Misrakesi's adventures in love and power continue. n

(Arshia Sattar is a teacher, critic and the author of abridged translations of Kathasaritsagara and Valmiki's Ramayana, as well as Lost Loves: Exploring Rama's Anguish)