The Buddha at Home

PILLAR FRAGMENTS, sandstone busts, stupa remains, carvings depicting the Buddha’s life: earlier this year, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, threw open one of the most impressive exhibitions of Buddhist art. Collected over several years, some hundreds of kilograms of valuable heritage travelled thousands of miles. Now these 100-plus objects form a part of the Tree & Serpent, an exhibition which runs until mid-November at The Met, as the museum is popularly known.

“It’s a complicated exhibition,” says John Guy, the museum’s Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia. Guy spearheaded the project, coordinating with multiple agencies, state and central governments. “It all came together in a remarkable way,” he says on a video call from New York.

The exhibition is a triumph of art—and logistics. Covid interrupted the planning, the people in charge kept changing and many of the objects were in far-flung regional museums. “This is an exhibition of extremely heavy antiquities… Retrieving these objects had its own particular challenges. They had to be handled in a totally professional way, with customised crates being built, professional art handlers collecting the works and transporting them to airports and assembling them in Delhi for final inspection and approval. And then air shipments to New York. So, a complicated logistical exercise, requiring military precision.”

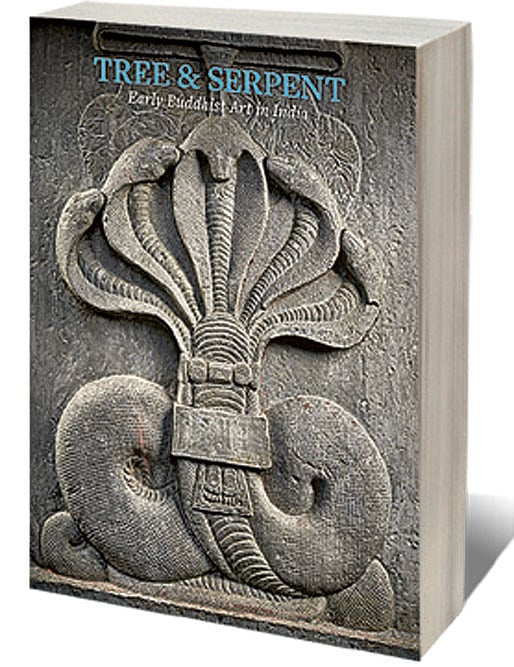

An eponymous coffee table book has also been published along with the exhibition and features scholarly essays on Buddhist imagery, texts, commercial contexts and regional linkages (Mapin Publishing; 344 pages, 322 illustrations, ₹3,950). Guy gently demurs when asked to name his highlights at the exhibition. “Oh! That’s an impossible question to answer,” he says with a chuckle. “There are 125 objects drawn from around 200 BCE through to 400 CE. And it includes, I say, shamelessly, many highlights.”

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

A limestone standing Buddha, for one. A sculpture of Poseidon, that points to a developed trade with the Romans. A detailed panel showing the Buddha’s renunciation from Phanigiri in Telangana.

India is considered the birthplace of Buddhism. Born in Lumbini, in present-day Nepal as Prince Siddhartha, Buddha, as he came to be known, renounced palace life and turned ascetic.

“You can regard the historical Buddha and the Mahavira, as reformers reacting against institutionalised Brahmanism and the authority of the priesthood,” says Guy. He cautions against using the word “Hinduism” as we understand it today, instead calling it “Brahmanism”. He likens the Buddha to Martin Luther, the German reformer who challenged the Catholic church in the 1500s. “[He’s] reacting to the control of the priesthood, and trying to identify an individual spiritual path that doesn’t require the intervention of priests through his teachings. And Martin Luther essentially did something rather similar, in what became Protestantism in Northern Europe.”

Buddha mostly lived, preached and died in the Magadha region, in northern India. He never travelled to southern India, but his teachings did. Newly discovered stupa sites in the past few decades in northern Karnataka and Telangana confirm that the region contains “some of the greatest surviving art anywhere in India”. These partly triggered the idea for the exhibition. Guy argues that Buddhism in the Deccan is as rich, vibrant and well-developed as its northern counterpart, even if neglected in scholarship and popular understanding. Tree & Serpent hopes to correct that imbalance.

But that’s not the only gap it addresses. Broadly speaking the modern understanding of Buddhism has been driven by 18th and 19th century European perspectives. While Sanskrit scholars and Indologists did “commendable work”, according to Guy, much of it was “from a textual perspective”. “Very few of them had any real understanding of what the reality of Buddhism was on the ground in this early period,” he says. “The shift increasingly now in the 21st century is much more on Buddhism as the archaeology will inform us, and then going back to the texts and revisiting them and easing out new interpretations from those texts. So I think there’s a much more balanced perspective emerging in modern scholarship.”

Monastic and stupa complexes abound through present-day Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. The religion flourished through trade and the development of urban centres. “The Buddhists were not shy in the propagation of their faith,” Guy writes in his introduction to the book, “and, for more than a millennium, succeeded.” Today Islamic invaders are widely believed to have pillaged temples, and turned them into mosques, but Buddhism was perhaps not all that different. Sacred sites dedicated to other deities were “commandeered and repurposed for Buddhist use,” Guy writes, “fitting a wider pattern of religious appropriation of sacred sites in South Asia.”

Buddhism flourished under the Mauryan empire in particular, through the third century. Scholars generally do not point to a single cause for the decline of Buddhism. But by the 12th century it had become marginalised. “The whole demise of Buddhism [question] is a complicated one. The conventional orthodox views say the coming of Islam spelt the end of Buddhism,” says Guy. “It’s not a full explanation and nor is it a fair one. Buddhism already had major problems way before the arrival of Islam in eastern India.” In many parts of the country, “Buddhism was losing its grip, partially due to a resurgence in Hinduism. And the sort of beginnings of bhakti, devotionalism, that really drove popular Hinduism from a very early period.”

Over time, monastery complexes and stupas suffered. “Just as they appropriated and subjugated the nature cults of early India, so Buddhist sites were in turn either abandoned or given over to Hindu temples,” Guy writes.

Both the book, and the exhibition are titled ‘Tree and Serpent’; references to key motifs of Buddhist art. Buddha found enlightenment under the sacred Bodhi tree at Gaya. Protective serpents are also prominent in the folklore.

Guy says the exhibition has already been drawing “very good crowds”. After its run at the Met, it will travel to the National Museum of Korea in Seoul. There are no plans yet for an Indian exhibition, although the bulk of the displays are from here and will likely return next year. “So who knows?” he says. “It would be nice if it happened.”

Institutions in India that loaned objects included the National Museum in Delhi, the Telangana state Museum in Hyderabad and the Allahabad Museum in Prayagraj. Smaller museums such as the Karimnagar Archaeology Museum and Kanaganahalli Site Museum also participated. Guy visited all these places and other field sites starting in 2014.

When dealing with such old objects, how do you guard against interpreting the past with the lens of the present? “Well, of course, history is interpretation, history is how you choose to piece together bits of evidence and to create a narrative that’s plausible,” says Guy. “History is only true to the extent that it has a high level of plausibility or credibility. That it is an interpretation, you must not lose perspective on that. We have the framework of historical facts, dates, people, individuals, and so on, but the narratives you build around those are shaped by your particular orientation as a historian, and your position in terms of how you see the dynamics of history.”

GUY JOINED THE Met’s Asian department in 2008 after working as a senior curator of Indian art at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The skills required to be a curator are not quite the same as a university professor, he says, even though the scholarly apparatus might be. It’s about, “being an educator in the widest sense and all curators are essentially educators”. “Our job is to do research and to share knowledge in various ways,” he says.

But in recent years, museums have faced a variety of challenges. In the past year alone, institutions have tightened security measures as climate activists have taken to vandalising art works to highlight their concerns. Around the world, works of Van Gogh, Vermeer and Degas have all been targeted. In June, protestors also rallied at the Met, but did not attack any of the exhibits.

“It’s not to do with art but to do with environmental concerns which are real,” says Guy. He sees reflections of the activists’ concerns in Tree & Serpent. “One of the subjects of the exhibition is the Buddha’s message to do with compassion for living beings and the protection of the environment, which are embodied in some of the Ashokan inscriptions and also in some of the Buddha’s own words and teachings. These we have foregrounded because they’re a real and immediate concern to all of us who share this planet.”

As museums stayed shut through the pandemic, many had to improvise. Guy believes museums will continue to play a significant role in society. “My feeling is, museums are a little bit like physical books, not Kindle books, in the sense that museums have a very positive future,” he says. “The further and further we move into artificial intelligence, into life on the screen with that element of detachment, the more I think people will flock to museums for the reality of the real thing. Just as holding a book in your hand is so important. I’ve no doubt in my mind that people always want to come to museums to have that one-to-one experience of standing in front of an object, which has the power to transform.”