The Brazen and the Devout

ANDAVAN PICCHAI, A 20th-century poet and composer, and a devotee of Muruga, wrote poetry in moments of spiritual intoxication, forgetting all else around her. She believed Muruga, “the eternal poet”, was speaking through her, a mere “pen-holder.” Throughout her adult life, Picchai finds herself compelled to write, despite competing responsibilities and familial pressure to abandon the practice. In one poem, Picchai writes, “Call him a madman. / Call him a ghost. / Still/ he draws me, Mother.” These lines lingered with me. The wealth of contradictory emotions held in these simple words impressed and moved me. I have wrestled, as many have, with the idea of god as a lunatic holding the keys to the universe. I, too, have experienced him as a fleeting spectre. Frustration, doubt, and outright bewilderment have accompanied my relationship with god. Still, he attracts my attention, my secret belief.

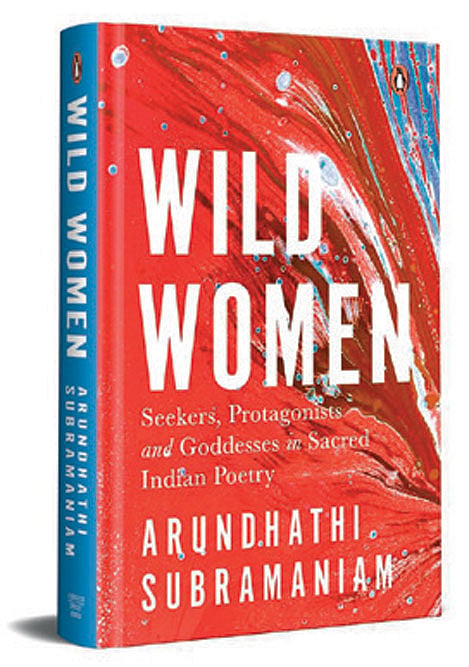

Lacking religion, I have struggled to articulate the strangeness of my connection to god. It can often feel like a game whose dimensions and rules have been arbitrarily created by me. God has most often appeared to me in well-timed coincidences—the appearance of a favourite bird before a difficult conversation or after fleeing a terrible incident, finding a female cab driver who shares a name with one of my favourite people. I picked up and put down Wild Women: Seekers, Protagonists and Goddesses in Sacred Indian Poetry (Ebury Press; 428 pages; ₹999) a new anthology of sacred poetry edited by Arundhathi Subramaniam, many times before I could finish it. Many of the poems were of sociological and aesthetic interest to me, but an equal number surprised me.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Wild Women is a many-headed beast. Compiled over five years, the collection hosts an astounding number of voices representing multiple movements in spiritual poetry in India, ranging from the 3rd century to the 20th. There is little uniformity in the manners in which these poets choose to commune with god, and there is little adherence to modern notions of sacrality, restraint, and realism. These poems, as is characteristic of Subramaniam’s writing, make for a demanding and rewarding read that upends expectations and challenges our contemporary poetics.

Picchai is but one of many voices in the collection that resonated with me as both a reader and a poet. There is wonderfully fresh and evocative imagery in these poems which transcend leaps in time and differences in culture. When Kamalakanta Bhattacharya writes that the naked woman is “robed in sky,” the reader receives that image with awe and recognition. Similarly, Ambapali describing her hair as being “the colour of bees” allows for a dynamism in our reading. Writing in an enraged Radha’s voice, Jayadeva addresses Krishna, “dark from kissing her kohl-blackened eyes, / At dawn, your lips match your body’s colour, Krishna.” In this poem, the images entirely carry the narrative.

When I ask Subramaniam what exposure and relationship to craft the poets of old may have had, she explains, “I certainly don’t think that this is craft in quite the way the modern creative writing class understands it. And yet, many of these poets were meant to be sung, and were surely aware of the parameters of their chosen genre of musical composition.” This is evident in the skilful use of anaphora, epistrophe, and more general repetition seen in these poems, and how the musicality of the verse underscores the depth of feeling.

Subramaniam says, “In the finest sacred poems, we are often in the presence of a heightened awareness. This doesn’t always make for poems of trailblazing literary merit, but it makes for poetry that lingers in our collective consciousness. There is a reason why Meera, for instance, still pervades our cultural imagination.” She argues, “[Meera]’s poems may be simple unvarnished lyrics, not particularly sophisticated. But her song leaps from the human voice to the stars. It is a voice of such vulnerability and abandon that it compels us to listen. It is conscious, scorching, pared down to the essentials. This kind of poetry finds its own form, creates its own genre, makes space for itself, exists on its own terms.”

The effects Subramaniam speaks of are far removed from how we consume contemporary poetry. It has me questioning what else existing on its own terms allows for. Though the merging of the sacred and the profane in the arts is not unfamiliar to me, I was taken aback by the unobscured sexuality in these poems. Passionately devoted to Lord Venkateshwara of Tirupati, Tarigonda Vengamamba, a widow in the 18th century, wrote, “…on my breasts, with his own hands,/ [He] [p]layfully rubs a sandal salve to / Cool my burning flesh:/ Slowly guides me to his chamber…” In her own time, she was considered sacrilegious and possibly insane. Brahmin priests attempted to bring her to heel and chose not to preserve the bulk of her writing. Vengamamba’s work is bold, transgressive, and defiant. The risks she takes in her poems are divorced from questions of metre and human morality. There is but one witness to her life: Venkateshwara.

Sidestepping brokers of spirituality and accessing god directly—intimately even—is a common theme in Wild Women. There is tremendous anti-caste, anti-patriarchal energy in these poems. Among the women these poems are written by and about are women whose caste and widowhood denied them power, slaves, prostitutes, and “mad” women. Kallave and Punnika use logic to challenge and dismantle entrenched Brahminical beliefs. Soraya, a Marathi Dalit poet, wrote, “I find it odd; / Those who know nothing, speak most of God.”

Hinduism forms the context in which many of these poems were written. I asked Subramaniam if she struggled with the harm religions have caused as she compiled this collection. She says, “Every faith has its shadow side, doesn’t it? I’ve known people of every religion who have had to confront some dark aspects of their inheritance.” For her, the collection was about “discovering voices that question hierarchy of all kinds.” Among the examples she offers are “the eighteenth-century Brahmin widow, Avudai Akkal, [who] asks her share of hard questions about why menstrual blood or saliva should be considered impure,” and “the nineteenth-century courtesan poet, Peero, disdainful of the orthodoxies of both Hinduism and Islam.”

She points out that these are but a few reminders of “the kinds of questions sacred poetry has always embodied.” But for her, the value within these poems extends beyond that. She hopes that “they will remind us of the profound truths that the many wisdom traditions of this land still enshrine.” Her journey has been about “discovering that there are living contemplative and ecstatic traditions in this country—immeasurably rich, vibrant, diverse and worthy of documentation and celebration. It would be a tragedy to get stuck with the exoteric aspects of faith and overlook the inner fire that animates it.”

Accompanying the intense sensuality in some poems is an emphasis on physical detachment in others. There is a haunting conjuring in these pieces of a state of mind and a place where, as Kabir writes, “There’s no moon or sun,/ no day or night,/ but brilliance/ without light.” Gangasati wrote, “The Guru stands apart from the universe, / let me take you to this sacred place.” Subramaniam says, “When insight hardens into institution, epiphany into tenet, poetry into punditry, the inner journey ossifies into religion. Journeys draw seekers. Destinations draw gatekeepers.” The women featured in the collection are “seekers who seek to become conduits, not custodians of the sacred.”

In times of religious extremism, she believes poetry can remind us of “other ways of ‘knowing’.” She says, “[Poetry] is an invitation to a fluid and multidimensional truth….that’s why we need poetry to counter the fundamentalists of every hue in our cultural, political and religious life. The wonderful thing is that the human love of verse is innate and primal. It should not be too difficult to reclaim this love.”

Subramaniam’s interest in a multi-dimensional truth is one of her strengths as an editor. The scaffolding she offers for each of these poets is instructive. There is no easy way to access the lessons within these poems. The value of such an anthology may be in what it asks of a reader: enter, listen, travel.