Searching for Homes

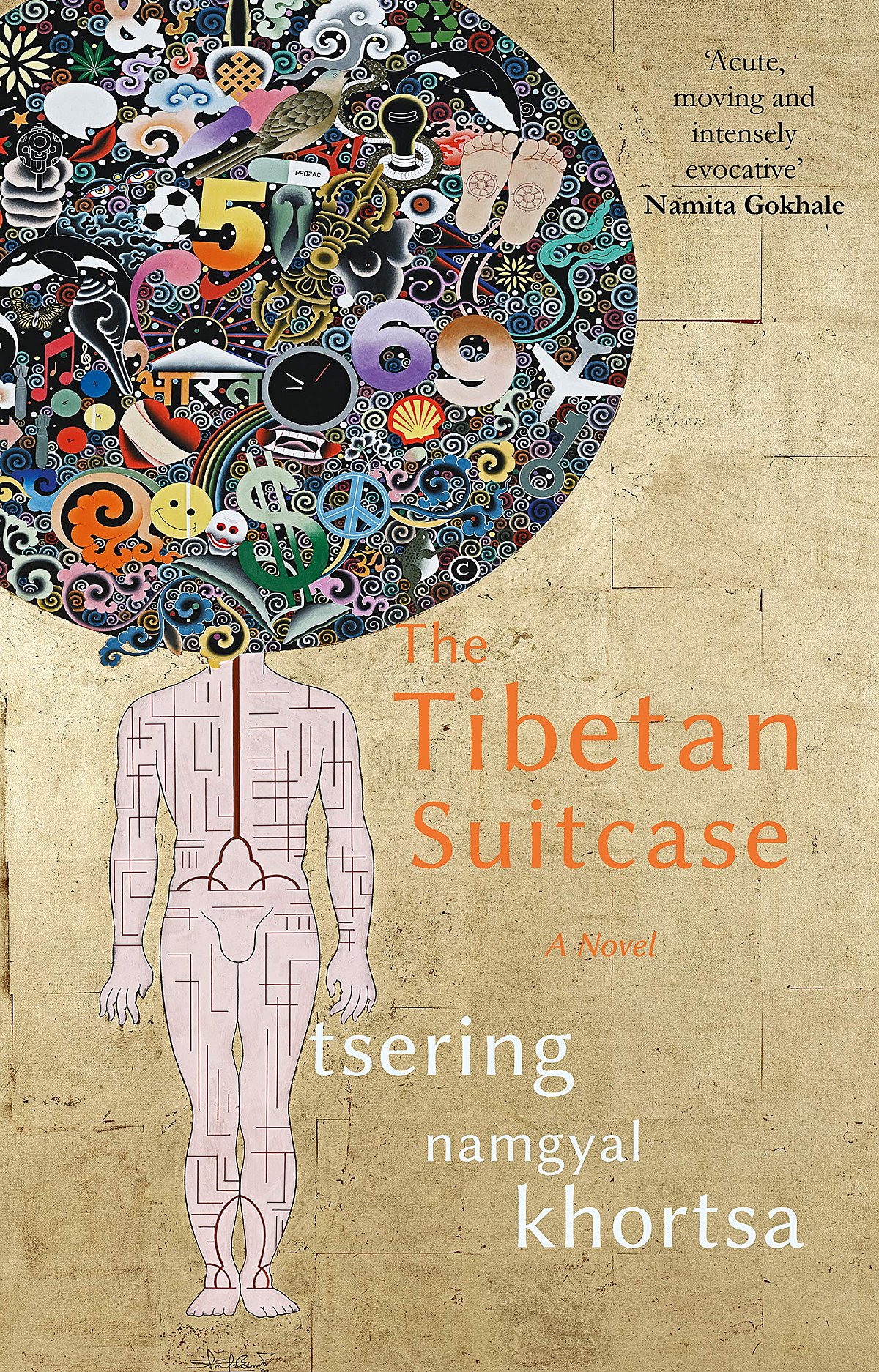

There’s a saying in Padmasambhava’s 8th century text Bardo Thodol, “Do not meditate at all, since there is nothing upon which to meditate. Instead, revelation will come through undistracted mindfulness—since there is nothing by which you can be distracted”. Journalist and author Tsering Namgyal Khortsa’s book, The Tibetan Suitcase is a meditation into this quest of attaining deeper mindfulness, personal and political. It struggles to the very end to delve into the exiled mind—at the same time, also questioning if at all it is just the mind that cannot be sent to ‘exile’. He happens to be the fourth Tibetan in exile in India to experiment with the genre of the novel. Among his other works are an essay collection —Little Lhasa: Reflections on Exiled Tibet (2006) and His Holiness the 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje: A Biography (2013).

Bardo, the Tibetan term carries with it connotations of not just afterlife but an in-between existence between death and rebirth. It is this liminal space that allows for greater enlightenment and knowledge. Can a genre of writing or any creative work be also caught in the bardo? Ann Tashi Slater opines in her article ‘Writing and the Tibetan Book of the Dead’: ‘Writing is a kind of bardo because ordinary life recedes as we create a universe on the page.’

Geographically, Tsering’s book spans broadly across two continents but there’s much more of an expanse that is not touched upon in detail, leaving some gaps. The narrative voices cum epistolary format along with multiple authors (collectors, in fact) make for some phenomenal disruption. Is this a hint towards perseverance? Tsering says in the preface he wanted ‘to leave room for readers to imagine....in deference to the Tibetan culture of reticence and taciturnity.’

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The Tibetan Suitcase might be a simple one-day read in the sense it is accessible and jargon free. However, every word is also a glass full right up to the brim in Tibetan Buddhist philosophy, which makes it taxing. All of which also perhaps gets lost in English—case in point being the impossibility of translating the notion of ‘emptiness’. The process of journaling diasporic lives and the epistolary form takes Tsering—the editor, collector, documenter a long way. Though the contents inside the ‘suitcase’ reveal the lives of Dawa Tashi, Iris, Brent and Khenchen Sangpo, it also revisits other sources on Tibet (The Himalayan Quarterly for instance), and authors like Amdo Gendun Chopel, The Dalai Lama, Sogyal Rinpoche among others.

But this book is not focussed on conventional dialogues or a single protagonist. There are pauses, memories and emotions in the back-and-forth letters/journal entries that one can pay attention to. In one series, we see how the fetish with Tibet and Buddhism has blinded the Western world (“People think all Tibetans are monks”, “Tibet, which the West considers a Shangri-La” etc). It creates, for Dawa, a never-ending conflict between his leanings for academia, romance and nostalgia as it were. He is drawn to Iris, a student of Tibetan Buddhism who tries to raise awareness for the Tibetan cause globally. Through the minds of these two characters, we see a Tibet, which isn’t the “simulacra of Lhasa” or the idealised homeland in strife under China. The layers make for an interesting discovery of the refugee predicament.

Tsering’s account of Tibet is also one that exists in the collective memory of its refugees, its diaspora and those hunted down by the armed groups for seeking freedom from years of oppression. Towards the end of the book, where Brent’s journal entries dominate, crucial and frustrating questions of Tibetan identity/citizenship are discussed. It is here that scholar Khenchen Sangpo’s role comes to the forefront—his works had already placed the contentious rhetoric of a borrowed homeland in front of the world. One wonders at the patience it takes to flesh out these entangled narratives and not solely rely on refugee numbers and figures. There’s a lot of controlled rage in the pages and rightfully so. It is perhaps an anecdote for the Tibetan exile condition too. Yet, this is fiction that feels like non-fiction unfolding in front of our eyes. Not all of that is untrue either. Tsering deserves adulation for that.