Ashoka: The King Who Said Sorry

IN 1837, JAMES PRINSEP CRACKED the Mauryan Brahmi script and George Turnour soon connected the Devanampiya Piyadasi of the inscriptions with Ashoka of the Sri Lankan chronicles. This sensational discovery opened a vast and unique corpus of inscriptions to the world. Ashoka (reigned c. 268- 232 BCE) was never a forgotten king—he strode like a colossus across the Asian Buddhist world. But this was a different Ashoka, a king who personally designed a universal morality and made its propagation the cornerstone of his political philosophy and policy.

Vincent Smith’s Asoka: The Buddhist Emperor of India (1901) was the first full-length study, but there were many thereafter. Romila Thapar’s Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (1961), still going strong, locates Ashoka in the history of his dynasty and offers a comprehensive account of Mauryan polity, economy, society and decline. Charles Allen’s Ashoka (2012) is actually about how 19th century antiquarians and archaeologists re-discovered the emperor through his inscriptions. Nayanjot Lahiri’s Ashoka in Ancient India (2015) situates the ruler in his archaeological landscape, and explains how his inscriptional messages would have been received in different ways in different places. Countless other books and articles have been written on Ashoka, from a variety of perspectives. His celebrity status (there is even a Bollywood film on him) means that many preconceived ideas have to be set aside.

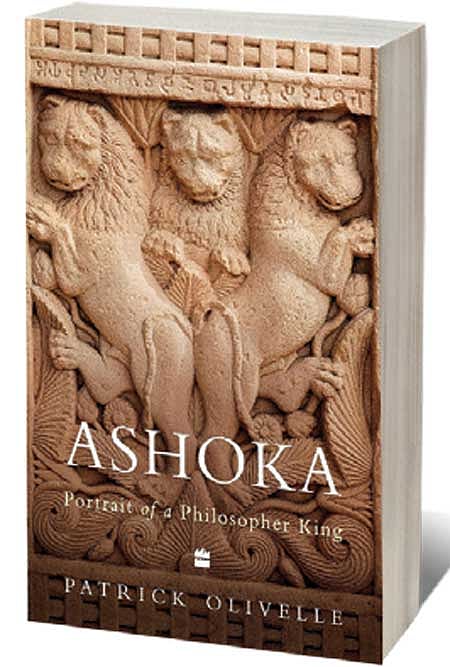

Patrick Olivelle describes his Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King (HarperCollins; Indian Lives series; 400 pages; ₹799) as “a search not a story”. His Ashoka is “a unique and complex personality,” the only king in history who dared to say, “I’m sorry.” Olivelle is a Sanskritist of Sri Lankan origin who has produced authoritative editions and translations of a vast array of Sanskrit texts. His writings on themes such as dharma, asceticism, renunciation, kingship and law have had immense impact across disciplines. Due to the formidable range of his translation work, he reflects on words with care, sees resonances across texts, and identifies significant silences. He offers a critical and yet empathetic reading of Ashoka’s inscriptions, conveying several perceptive insights into the life and ideas of the ancient emperor. The translations of the inscriptions at the end of the book allow general readers to experience the flavour of Ashoka’s words.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

An important respect in which Olivelle’s book differs from others is that he does not use Buddhist legends or Kautilya’s Arthashastra as primary sources for his narrative. There are good reasons for this. The legends reflect the end product of a long process through which Ashoka was canonised and presented as the greatest Buddhist king the world had ever seen. So the dramatic stories in texts such as the Ashokavadana—for instance, that he built a hell on earth where he enjoyed watching prisoners being tortured, or that he had 500 women of his harem burnt alive when they cut the branches and flowers of an Ashoka tree—are not included, even as allegory. Neither are the stories in the Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa about Ashoka’s famous children Mahinda and Sanghamitta, who are said to have sailed to Sri Lanka, taking Buddhism along with them. A great deal of ancient Indian history has, in fact, been written by carefully sifting through, comparing and interpreting legends and Olivelle is too sophisticated a scholar to dismiss them as patently false. But he points out that they reflect later imaginings that served the needs of people who constructed them. He cannot be faulted on this.

It is well known that the Arthashastra does not describe the Mauryan (or any other) state. It is a sophisticated theoretical treatise which contains a brilliant delineation of a potential state. Olivelle has himself contributed towards establishing that although some of the ideas in the Arthashastra may have been circulating in the Mauryan period, the text itself was composed in stages at the cusp of the millennium. It is also well established that the legend connecting Kautilya with Chanakya and the Arthashastra took shape many centuries later, in the 4th/5th century CE. So the Arthashastra does not describe the administrative system inherited by Ashoka from Chandragupta Maurya.

This leaves us with one unimpeachable contemporary source of information for Ashoka that is unavailable for any other ancient Indian king—his own words, inscribed on rocks and pillars across the subcontinent. These are mostly in the Prakrit language and Brahmi script, but in the northwest, Ashoka chose to use the Kharoshthi script, Greek and Aramaic. Even if Brahmi pre-dates Ashoka (as suggested by graffiti on potsherds from Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka and sites such as Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu), Ashoka produced the first corpus of royal inscriptions in India. In this and many other respects, he was an innovator. Historians usually consider Ashoka as his personal name and Devanampiya and Piyadasi as epithets. Olivelle suggests that he had two names—Piyadasi and Ashoka. Some of the edicts use the first person, some the third, but there is no doubt that they represent the king’s own ideas. Olivelle calculates that these “speaking stones” contain some 4, 614 words. He describes Ashoka’s compositions as his “writings,” recognising editorial interventions, as well as the fact that they also existed in multiple oral and performative forms.

THE MAURYAS inhabited a fast-changing Eurasian geopolitical world and Ashoka embraced this world with confidence and enthusiasm. Olivelle speculates that he probably grew up in a cosmopolitan and multi-cultural atmosphere and this may have had a long-term impact on his thinking. Ashoka mentions his Hellenistic contemporaries by name and claims to have engaged in various welfare measures and dhamma propagation in their domains. There are tantalising allusions, but unfortunately no definite references, to Ashoka in western sources.

Olivelle’s Ashoka is a strategic thinker whose ideas evolved over time, who took delight in the creative ambiguity of words and used writing “as an instrument of good governance and mass education.” The author points to the inscriptions’ high literary qualities, their skilful use of word play and alliteration, their madhurya (sweetness, charm). Most importantly, he tracks the evolution in Ashoka’s ideas over his long reign. While there is a consistent importance given to effort and striving, there were changes in language, ideas and approach—shifts from commanding to inspiring, from giving specific examples of dhammic conduct to abstract articulations of virtue, from self-reflection to arrogance.

Ashoka’s relationship with religion was complicated. Olivelle refers to the inscriptions’ deafening silence about core Buddhist doctrines as well as the presence of elements of the Buddhist duty-oriented social ethic, including non-violence. ‘Conversion’ is a misnomer, but there is no missing the ardour in the emperor’s expression of faith in the Buddha, dhamma and sangha, his concern for the sangha’s unity, and his interference in its affairs. Olivelle suggests that Buddhism was probably already well-established and widespread by Ashoka’s time. However, archaeological evidence from sites such as Sanchi, Taxila, and Bodh Gaya suggests a significant increase in the popularity of the Buddhist faith in the Mauryan period. The fact that the great emperor had his edicts inscribed near Buddhist sacred places or monastic complexes must have enormously raised the prestige and profile of the sangha and greatly annoyed their rivals.

Olivelle alerts us to Ashoka’s pivot from being an ardent Buddhist to a propagator of a universalistic dhamma (he dates this to around 265 BCE, in the thirteenth year after his consecration). Dhamma forms the central topic of the major rock edicts and pillar edicts; it is mentioned over and over again, on its own and in compound words. Ashoka was a man with a mission who saw himself as an exemplar and prophet of dhamma. Not content with inscribed pronouncements that few of his subjects would have been able to read, he used state bureaucracy to propagate dhamma, and created a new cadre of dhamma officers. He himself went on dhamma tours to propagate it. If dhamma must be translated, it can be understood as an umbrella term for goodness, which included specific virtues such as nonviolence; compassion; truthfulness; thriftiness; purity; giving gifts to shamans (renunciants) and Brahmins; obedience to parents and elders; regard to friends, companions and relatives; and proper regard to slaves and servants. Olivelle discusses the treatment of dhamma in chronological order and identifies subtle shifts in the specific virtues mentioned.

ASHOKA CONSIDERED himself an enlightened, benevolent patriarch ruling over a political and moral empire. His concern and constituency extended beyond humans to animals to all living beings. Much has been made of his espousal of religious ‘tolerance.’ What he was talking about was something much more positive and meaningful—respectful and creative dialogue between the religious communities that he referred to as pasanda, an important word which Olivelle discusses in detail. There must have been tensions and conflicts among these groups, and it is remarkable that a powerful plea for religious concord came from a man who had strong personal religious convictions.

Olivelle draws attention to the things that are not included in Ashoka’s descriptions of dhamma. These include crimes such as drinking and sexual misconduct (though it can be argued that these are implied in some of the abstract virtues that Ashoka emphasised). Apart from frequent references to Brahmins, Ashoka does not mention varna, which is often misunderstood as the cornerstone of ancient Indian society across the centuries. But he was acutely aware of high and low in society, and emphasised that the path of dhamma was open to all. In spite of this and the references to women in the inscriptions, Olivelle suggests that in his dhamma discourses, Ashoka especially had an audience of well-to-do, male householders in mind.

Ashoka’s dhamma has been variously seen as upasaka dharma (the dharma of the Buddhist laity), raja-dhamma (the dharma of kings), universal religion, and as Ashoka’s own creative invention. It has been seen as a legitimation strategy used to weld together a vast and variegated empire. Olivelle’s understanding has elements of all these interpretations, but is more nuanced. He tries to theorise dhamma and bring it into a larger, global discourse on politics. According to him, Ashoka wanted to provide a lingua franca and a common identity to the people over whom he ruled. His dhamma was a form of ecumenism, a civil religion that created a “dharma community”.

Ashoka looms large in Indian (and Asian) history. Although he was ‘cancelled’ by Brahmanical tradition, Olivelle argues convincingly that he played an important role in redefining the concept of dharma, injecting it with moral content. His suggestion that the Dharmashastra idea of samanya dharma (the dharma applicable to all) could be part of an Ashokan legacy is attractive, though perhaps it can be seen as part of a combined Buddhist/Jain/Ashokan legacy.

Ashoka would have been delighted that over 2,000 years later, he is remembered and admired for his eschewing of war, his commitment to the welfare of people and animals, his ability to think and act beyond the boundaries of his own empire, his commitment to morality, and his untiring efforts to propagate ethical living. The selection of Ashoka’s Sarnath lions as an emblem to represent the aspirations of independent India reflects Jawaharlal Nehru’s fascination for what Ashoka and the Mauryas stood for. Ashoka’s emphasis on nonviolence, guarding one’s speech, and promoting inter-religious dialogue and concord are especially relevant to our times. But there is also a less attractive aspect of Ashoka’s persona—his self-righteousness and arrogance. A single-minded state-sponsored ideological programme based on preaching and policing (even if, as in this case, apparently based on benign and noble sentiments) is a form of authoritarianism, even tyranny.

Patrick Olivelle states that this book is for general readers, not scholars, but it brims with many valuable insights for both. The pièce de resistance is the beautiful dedication: “To Chapada, and to his fellow scribes, engravers and stonemasons, whose toil and sweat made it possible for Ashoka’s messages to be read by us twenty-two centuries later.” It reminds us of those we forget when we remember Ashoka, the philosopher king.