The Lost Children

With schools remaining closed, tracking the progress of students has become a challenge in itself

/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Lostchildren1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

THE SIX CLASSROOMS at the Government Higher Primary School (GHPS) in Kallubalu near Jigani on the outskirts of Bengaluru remain padlocked. It is the time of day when boys and girls, dressed in the familiar blue accoutrements of childhood, line up in the corridor for a glass of milk, but it has been over a year since the school, like most others in the country, fell silent. The teachers—three of the six teaching staff are away on Covid-19 contact tracing duty—sip strong tea in a room with blue shutters and admit to a reduced workload and greater anxiety about their students. “The children have lost weight. Some go to work with parents, some sell vegetables by the roadside,” says S Saritha, 33, who teaches English. “We can make up for the loss of learning, but the loss of health and innocence could be permanent.”

The wall behind her is dominated by a yellow chart with the names of 119 children, the strength of the school in January—they have since added 40 more, at least half of whom were pulled out of budget private schools because their parents could no longer afford the fees. There are mobile phone numbers against most names on the chart. “Every day, we share basic homework and course material over a WhatsApp group, but only two-thirds of the children have access to smartphones, and even then, the parents take the phone to work and they may only get an hour or two in the evening to catch up on studies,” says 42-year-old Farzana Akhtar, the Kannada and social science teacher who began her teaching career 18 years ago at this school. It has been an exhausting year for parents, and despite the state government’s refusal to keep schools open over fears that the virus would spread faster, teachers and civil society organisations have exercised what little agency they have to keep in touch with children.

In August 2020, the Karnataka government had launched Vidyagama, an ambitious programme to take school education to the doorsteps of children by having teachers engage with them in public spaces in their neighbourhood, only to suspend it when stray cases of infection among communities in Kalaburagi district were blamed on the classes. There was another problem: gatherings in the village were also bringing caste and class differences to the fore in ugly ways. The second edition of Vidyagama, which ran for three months starting January 1st, aimed at bringing children back to the great social leveller that was the school environment. Children attended school in smaller batches, for a couple of hours at a time, two to four times a week. “Classes were held in the corridor, and much of the time was spent making sure they had course material, workbooks and a supportive environment at home,” Akhtar says. With a second wave sweeping the country, education and child welfare have once again become the first casualty. “We have had to suspend Vidyagama because of the second wave,” Dr K Sudhakar, minister for health and medical education in Karnataka, tells Open. “For those who question this decision, I want to reveal that in the last 20 days of the second edition of Vidyagama, 8,000 students across the state were infected. Congregation in close proximity whether indoors or outdoors presents an undeniable risk. The government cannot take sole responsibility for everyone. While we are very concerned that children must not drop out, saving their lives is more important than their education,” he says, adding that the ministry wants to undertake a health and nutrition audit of children to assess “the collateral damage of keeping schools closed”.

According to a five-state study in January by Azim Premji University, 92 per cent children have lost at least one language ability from the previous year and 82 per cent have lost at least one mathematical ability

Educationists allege that unlike Andhra Pradesh, which has elected to keep schools open despite the spike, Karnataka has been callous in enforcing shutdowns across the board. “Sixty per cent of government schools in the state have a total strength of 20-30 children—there is little risk involved in keeping them operational. Gram panchayats should have been empowered to decide on which schools can remain open,” says Gurumurthy Kasinathan, of IT for Change, an organisation that works to leverage technology for development. “The government wants to use teachers as unpaid labour for Covid testing and tracing duties, without prioritising their vaccination,” he says.

Children of migrants are unarguably the most vulnerable group in the school system and the GHPS in Kallubalu, Anekal taluk, is almost entirely populated by children from northern districts like Yadgir, Raichur and Belagavi. From a relatively carefree life as a schoolgoing child, R Bhavani, a Class 8 student, has had to shoulder responsibilities beyond her years. Her parents work in a garments factory and leave her in charge of the small tenement, of making lunch and dinner, and of monitoring her younger sister Rajeshwari, who attends Class 5 at the same school. “Father tested positive and had to be admitted to an isolation ward a couple of months ago. He has lost much of his strength and worries he may lose his job,” she says. The lanky Rajeshwari skips meals and often lands up at the school, asking when classes would resume. S Sanjana, a Class 6 student, is among the fortunate ones. While both her parents work in housekeeping at a factory, the family lives in a safe neighbourhood, occupying the ground floor of a house at Rs 4,500 per month. For the past two months, her elder sister Surekha, who has moved in with the family, has kept her company, managed the household and helped with schoolwork. Sanjana misses morning prayers at school, the company of friends and Saritha’s English lessons, but filling out workbooks provided by Sikshana Foundation, an NGO that develops learning modules for government schools, keeps her from losing interest in studies. She knows Muni Mahadeva, the mentor in charge of 500 children in Anekal taluk, will knock on the door every 15 days and sit down with her in the common portico to analyse the progress she has made. “She enjoys practising English writing but she has to focus on math. We are not worried about the school curriculum; we want to ensure that the children learn the basics,” he says. Since the lockdown in March 2020, 18 lakh students in state-run primary schools in Karnataka have benefited from Sikshana’s Project-Based Learning and Customised Learning Achievement Path modules. Prasanna VR, CEO of Sikshana, says that while workbooks and modules have been key to keeping students interested in learning, there is no substitute for going to school. “In the early days of the pandemic, the government seemed to have the will to open small schools, but it succumbed to pressure and took the easy way out. No one wants to take the risk,” he says.

According to a study in January by Azim Premji University titled ‘Loss of Learning during the Pandemic’, covering 16,067 children in 1,137 public schools in 44 districts across five states including Karnataka, 92 per cent of children have lost at least one specific language ability from the previous year across classes 2 to 6—including reading with comprehension and writing simple sentences based on a picture. Eighty-two per cent of children have lost at least one specific mathematical ability, including identifying numbers, performing arithmetic operations and solving problems. ‘The extent and nature of learning loss is serious enough to warrant action at all levels. Policy and processes to identify and address this loss are necessary as children return to schools,’ the report says. Rishikesh BS, who teaches at the Azim Premji University’s School of Education and leads the Hub for Education, Law & Policy, says the study was undertaken to understand the gravity of the situation, but the findings turned out to be much starker than anyone expected. “The Karnataka government was receptive to the report and introduced Vidyagama in a new avatar, but now that there is another spike, it is the schools that stay shut while everything else in the state is functional. It is unfair that children are not being considered except in terms of passing examinations,” he says.

Muni Mahadeva, in charge of 500 children in Anekal taluk in Karnataka, knocks on every family’s door every 15 days and sits down with the children to analyse the progress they have made

The GHPS in Kallubalu has not had a dropout for the past several years, but Akhtar fears there may be three this year. “A boy from Class 7 has started helping his parents at their chicken stall and may not return to school. Two other boys, both academically promising, have gone back to Bihar and contacting them has not been possible,” she says.

Fortuitously, a PIL filed in November 2020 to address the gaps in access to online classes has led the Karnataka High Court to pass an overarching order asking the state government to ‘bring children back to the education system’. “Frankly, when we filed the PIL, we did not realise the repercussions it would have. The government has been caught out and is bereft of ideas, but it is being forced into action,” says Harish Narasappa, the advocate who argued the case. One fallout of the high court order is a door-to-door survey of all children in the state by the Rural Development and Panchayati Raj Department in order to track them better. “We have surveyed 40 lakh families since December, with 40 lakh more to go,” says Priyanka Mary Francis, commissioner, Panchayati Raj. Teams of three—including Anganwadi workers, and self-help group and panchayat members—have been engaged in conducting the survey, which includes an extensive questionnaire on school enrolment and reasons for dropping out. “We have also developed a protocol to re-enrol children who are out of school and we are in the process of training gram panchayat education taskforces,” she adds.

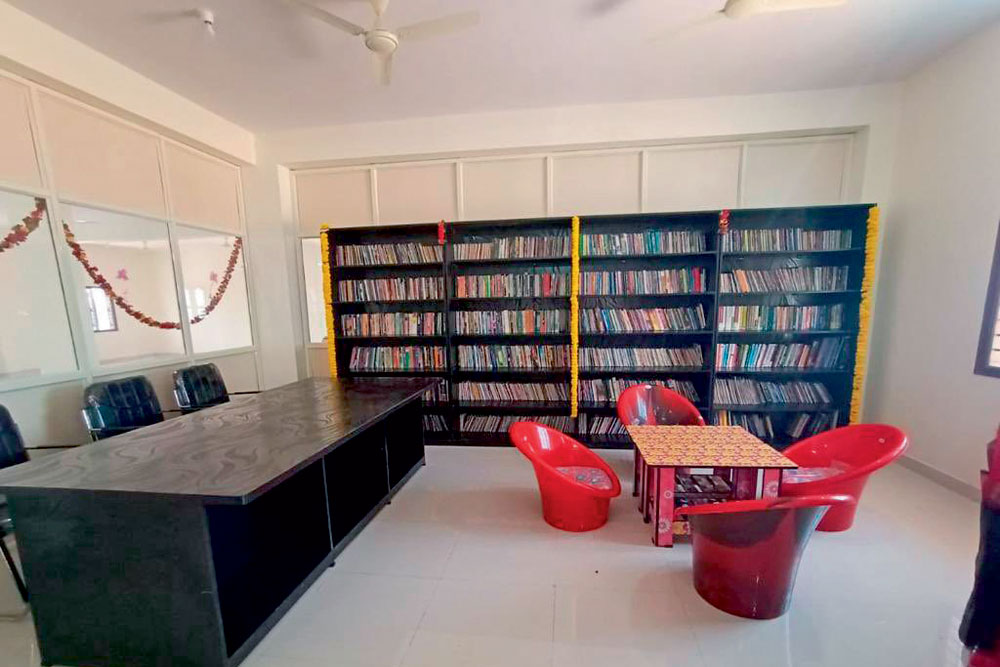

The department, under Principal Secretary Uma Mahadevan Dasgupta, has also pro-actively led a programme to turn 5,622 gram panchayat libraries into attractive learning and activity centres for children during the pandemic. “We envisage libraries as safe, clean community centres with sanitation and handwash, stocked with books, a digital library and a TV for screening lessons. The first thing we decided was to enrol all children between 6 and 18 for free. With schools shut, many first-generation learners lack a calming safe space to read or to play, and this is especially true for girls,” she says. With renovated buildings and a wider selection of books curated by NGOs like Pratham Foundation and Azim Premji Foundation, besides science and math activities—and even a reading corner with beanbags in one panchayat in Khanapur—the village library, in its new avatar, could plug glaring gaps in the school system during the pandemic and help children transition to full-time school later. The department is looking for ways and means to keep them open through the day, instead of just four hours, and has appointed an independent team to assess the impact they have had on society.

The utility of a safe space for children cannot be overstated. The pandemic has already pushed lakhs of children into manual labour, caused a massive uptick in the number of reported cases of child sexual abuse and enabled underage marriages. In districts of neighbouring Telangana where child marriages had been brought under control over the past decade, there is a new, worrying trend. In Atmakur mandal, Suryapet district, Vaysavayi Lalitha, a 43-year-old activist who works with MV Foundation, has intervened in 24 child marriages and stopped 18, much to the annoyance of locals who would rather get girls married early than leave them alone at home unattended. There are so many issues directly connected to school closures that addressing all of them is like catching an ocean in a sieve. “This year there are girls as young as 11 transplanting paddy. They work in groups of five to 10 and get paid about Rs 3,000-3,500 for a day’s work per acre of paddy,” says Lalitha, who tracks 3,000 girls between 11 and 18 years of age and estimates 60 per cent of them have joined the workforce since the schools shut in March 2020. “We have set up clubs for girls named after inspiring women like PV Sindhu, Indira Gandhi, Mother Teresa and Kiran Bedi. They look out for each other and alert us when something untoward happens to one of them.” With the Telangana government dithering on providing either cooked meals or dry ration to 20 lakh students in the state, there is shortage in the villages, not just of food but of sanitary napkins, soap bars and other essentials.

Karnataka is turning 5,622 gram panchayat libraries into learning and activity centres for children during the pandemic. The village library, in its new avatar, could plug glaring gaps in the school system and help children transition to full-time school later

At a time when underprivileged families have reached a point of drain and despair about the current state of the pandemic, there is a deafening silence on how the loss of midday meals, milk and eggs at school is adversely affecting child health. In the course of a project in Karnataka’s Raichur district, when public health researcher Dr Sylvia Karpagam happened to weigh children who appeared undernourished, she found them to be underweight. “At health camps for seniors I conducted in poorer neighbourhoods in Bangalore, I came across children with older diseases—marasmus, scurvy, rickets—indicative of nutrient deficiencies,” she says. “The idea that food is a right is lost on the government. So instead of predicting shortages and formulating strategies, the government has snatched away whatever safety net the underprivileged had before. The results of this gross neglect of child health and nutrition are sure to be long-lasting.” Instead of worrying about classes and board examinations, the state ought to snap out of its bureaucratic morass, so it does not fail all its children.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

‘Fuel to Air India plane was cut off before crash’ Open

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha