Repentance Song

One no-ball for money cost TP Sudhindra his career in cricket and his reputation. Twelve years later, he opens up to Aditya Iyer in Bhilai about that mistake and its aftermath

Aditya Iyer

Aditya Iyer

Aditya Iyer

Aditya Iyer

|

13 Sep, 2024

|

13 Sep, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Repentancesong1.jpg)

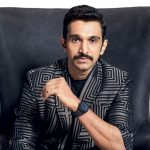

TP Sudhindra, 40, is currently head coach of the Chhattisgarh U-19 team (Photo: Govinda Sonkar)

On an early winter evening in steel country, Chhattisgarh, a junior-level officer at the Accountant General’s Office (AGO) in Raipur mounted his LML motorcycle to return home to Bhilai. He was used to the hour-long journey that awaited him on the state highway—one that traverses muddy land and dust-kissed skies, both hazy with the plumes emitted by the thousand or so chimneys of steel plants—having ridden back and forth daily for a few long months since he had settled into this line of work in the May of that year, 2012. But something was most unsettling and stifling about this October dusk, in the air and also in his mind.

About halfway to his destination, the officer noticed yet another truck hurtling down the opposite direction, but this one caught his attention as it was on a divider-less passage of the highway. So, he began to veer right, in the direction of the truck and gunned the accelerator. Full throttle. “I thought, let us end this all, let us just put an end to the suffering. I had had enough of it.”

Metres away from the collision, against the soundtrack of the truck’s blaring horn, there was another voice in the officer’s head and, luckily, it said this. “Kya kar raha hai, yaar? (What are you doing?)” And just like that, in the nick of time, he swerved away from certain death, skidded to the side of the highway, and dismounted to collect himself.

“I was shaking like a leaf, for 15 or 20 minutes, which is a very long time. But when I finally composed myself by the side of that road, I thanked God for giving me the strength to live. By the time I was on the bike, I also knew I had the strength to move on from my past, I had accepted what had happened. I told myself, ‘So what if I am banned from playing cricket, it is not worth taking my life for. I will make something of myself outside of cricket. I will study hard to become a gazetted officer. I will win my respect back and rebuild the name of TP Sudhindra.’ And that’s when I knew that I would turn my life around, just moments after attempting to end it.”

The officer is, of course, TP Sudhindra, swing bowler par excellence on the domestic circuit, who seemingly had it all in 2012 only for his life to crash and burn simultaneously. In January that year, he finished as the highest wicket-taker in the Ranji Trophy season, with 40 dismissals for his side, Madhya Pradesh. Whether those numbers put him on the radar of the national selectors or not, it did get him an IPL contract that he had so yearned for by February, signing up with the Deccan Chargers for a fee of ₹30 lakh. In March, he got engaged to his future wife. And by early April, he had taken his first IPL wicket, that of CSK’s Faf du Plessis.

Then came mid-May, the Ides of May, when a sting operation run by an Indian news channel had Sudhindra agreeing to bowl a no-ball for money, haggling for the right price to spot-fix in an inter-district T20 game. The fee he wants in the footage is ₹50,000, but is told he would receive ₹20,000. Sudhindra agrees. And before the half-hour, primetime show could end on India TV (his was the first of five such segments, which included hidden camera confessions by IPL cricketers Mohnish Mishra, Shalabh Srivastava, Amit Yadav, and Abhinav Bali), Sudhindra was an outcast, a cricketing and social pariah.

By October, he had tried to take his life and then moved on from a sport that had promised him everything.

So, why did he do it, why did he agree to bowl a no-ball for money (pittance money at that), is perhaps the most obvious question, and as I pose it to Sudhindra, now 40 and looking every year of it with a receding hairline and ample bulk, he manages a weak smile. “See, whatever happened has happened. But if you listen to my story, you will realise that I was trapped,” he says. “Not a single day has passed by where I have not regretted what happened. But my situation was such that I had stopped thinking clearly. And anyone else in my situation would also have fallen into the same trap. That’s why such traps exist, to catch people who are desperate to make it.

“I can tell you one thing right now, it was not for money. It was to find success after being neglected by the system. So, the short answer to your question is, yes, what happened happened, but the long answer offers more understanding and explanations. Do you want to hear the longer version?”

I do, and Sudhindra knows it. For close to nine years now, since late 2015, I had prodded Sudhindra intermittently to see if he was ready to tell his side of the tale. Always, he declined politely, often saying: “I am still hopeful of turning my ban around. The punishment is disproportionate to the crime. I have appealed to the BCCI once again, so once I am cleared, I will talk.” Finally, in February 2023, after 70 or so appeals that he wrote to the cricket board that were ignored and a single appeal at the Chhattisgarh High Court that was not, the BCCI ombudsman lifted his life ban with immediate effect. Then 38 years of age, he was too old to return to the field as he had dreamt of, but not a day too early to talk, at long last. A good year and a bit later, he kept his word.

Perhaps, he is a victim; maybe, he is not. But he sure is for real. Since the turn of the century, several cricketers have been caught, one way or the other, for taking a bribe. Few, possibly none, of them have had the courage to go into the details of why and how, preferring to fight the allegation, the ignominy, and the defamation in court or just choosing to stay mum. None of them have repented on a public platform. Sudhindra, now, is not one of them. This is a story of his infrequent highs and lows on a cricket field, and the very frequent lows off it, especially once he was banished from the game. More than anything else, this, then, is a story of his repentance.

We are seated across a metal table, on wobbly Neelkamal chairs, inside a shed at a private cricket academy in central Bhilai, so central that Sudhindra can simply point in the direction of a landmark in his life and I can see it. “That there, across this wall from the ground, is Kalyan College, where I enrolled to do commerce after my father fully stopped me from playing cricket to focus on my Class 12 exams,” he says. “For a full year, I had not played and I tried staying away from the game even after I joined college, well over 100 kilos in weight because of doing little else but eat-study-sleep. But this ground, and the smell of the grass, called me back.”

“They said an overseas league was interested in me. But the owners needed to know if they could trust an unknown player like me, so they needed me to prove myself. At first, I refused. But they said the management company would not be able to push for me if I did not do it and that I had nothing to lose because it wasn’t a big event. Plus, I would get paid for it. All I had to do was bowl the no-ball and later show them proof of having done it,” says TP Sudhindra

Education, for what he calls a “service class”, in this land defined by steel, is as tangible as steel. His grandfather, an electrical engineer, arrived here with his children from Andhra Pradesh in the seventies and to ensure that subsequent generations of this family would find employment in the steel authority or its many subsidiaries, book knowledge and marks were a must. “Even during my Class 10, my father asked me to not play cricket. But selection for MP’s Under-16 team was happening at the same time in Indore. So, I begged Papa to let me go. He agreed, thinking I would not get selected. But I did,” he says. “Anyway, after Class 12, with cricket this time fully behind me, I wanted to go to Pune to study further, in a college like Symbiosis. But my family could not afford the fee. That is when I realised, ‘haan yaar, maybe we really do have a money problem’.”

The older he grew, the more acutely aware he got of the financial crunch his family was in. “Back in those days, when I was in college, there was this brand of jeans called Killer. It used to cost, if I am not mistaken, ₹800. I told my older sister about wanting a pair. She ended up working extra jobs just to buy me one. I will never forget those days. Being from service class, I was not going to compromise on my education to play cricket. But because I was enterprising enough, I figured I could do both at the same time, without letting one affect the other.”

Enterprise came naturally on the cricket field too. It was as a top-order batsman that he was first selected in Madhya Pradesh’s age-group team. One day, their wicketkeeper got injured so he crouched behind the stumps and continued to do it successfully for a short while, but his fast-increasing height put paid to that. Then, in another game, all the specialist bowlers went for runs so Sudhindra rolled his arm over and picked up three wickets. “Just like that, I fell in love with bowling. I didn’t have any specialised skills, or care to, I just used to run in and bowl fast and enjoy the experience of beating a batsman more than ever scoring runs.”

He remembers when he first started to care. “It was the Moin-ud-Dowlah [Gold Cup] Tournament and I had just dismissed Jacob Martin with an outswinger. Not that I knew how to bowl an outswinger on purpose. Anyway, Rajesh Chauhan, my captain, asked me to bowl an outswinger to the new batsman also. I was too ashamed to tell him that I did not know how I do it and also it was too late. So, I held the shiny side towards the slips and let it rip. The ball swung in and I got hit for a boundary. Immediately, Rajesh Bhai yelled, ‘bewakoof!’ That day, I became a bowler.”

Chauhan remains Bhilai’s most famous sporting son, having represented India in 21 Test matches in the 1990s, and it is in his cricket academy that we sit, the Govind Chauhan Cricket Academy, named after his father. And it was Chauhan who came to Sudhindra with an offer from the Indian Cricket League (ICL), the privately-run T20 tournament in 2007 that would spawn BCCI’s Indian Premier League a year later. For Sudhindra, it was a no-brainer. “They were offering me ₹20 lakh per annum. I kept my family’s financial situation in mind and took it up. Plus, no one knew then that we would be banned from playing in domestic tournaments.”

There was another reason Sudhindra was keen to play in ICL. To bowl against some of the best international players in the world. “Brian Lara, Nathan Astle, Inzamam-ul-Haq, these are people we only saw on TV, or in our dreams. Now, I was bowling at them.” Not just bowling, dismissing too. In December 2007, while playing for Delhi Giants against Mumbai Champs, Sudhindra accounted for the wickets of Lara, Astle, and England’s Vikram Solanki in the space of minutes and ended up as the Man of the Match. “Uss din, khudh ke nazaron mein chad bhi gaye (I rose in stature in my own eyes).”

ICL went belly-up by end-2008 and in early 2009, 79 ICL players were granted amnesty by BCCI, including Sudhindra, who found himself at the bottom of MP’s pecking order for the upcoming domestic season, despite having been their highest wicket-taker for several seasons. “Chalo, but at least they had given me a chance to play in trial matches ahead of the Ranji season. In the first trial game against Punjab in Patiala, I went wicketless, and could not sleep for two nights. I thought, ‘OK, your career is over, you do not have it in you anymore.’ Then, in the next match in Chandigarh’s Sector 16 stadium, I took five wickets in each innings and laga ki, boss, mein abhi bhi zinda hoon (I felt alive again).”

That season, 2010-11, would be a season of highs for Sudhindra. It would also begin to cause his lows. This is how it went. By January 2011, his 23 wickets for Madhya Pradesh in the plate group of the Ranji played a pivotal role in his state qualifying for the elite group. Then, in February 2011, he was MP’s highest wicket-taker in the Vijay Hazare Trophy, the domestic 50-over trophy, and expected to be a shoo-in for the Central Zone side in the Deodhar Trophy. It did not happen. “When I asked the state association why I was not selected, they said my name didn’t come up in the meeting. But does a topper’s name have to be recommended?”

A month later, in March, Sudhindra blazed through the Syed Mushtaq Ali Trophy, the domestic T20 trophy, once again as the highest wicket-taker across teams with 14 wickets, dragging his side all the way to the final, where they lost by 1 run to Bengal. “My Mushtaq Ali numbers made me hope for an IPL contract because I knew team owners looked at these performances to fill their squad. But when it did not come, not even a call for trials, I started to break: bohot zyaada tootna chaloo ho gaya.

“I was told perform well and you will be rewarded. To perform well, I worked very hard, then I also performed. But when it was time to be rewarded with selection, it would not happen. I could not understand this. Digest nahi hua.”

There was one final kick to that non-digesting gut a month later in April, while the rest of the country celebrated his colleagues winning a World Cup, Sudhindra looked to secure his future with a sport quota job at the AGO Raipur. They selected a university-level player instead. “I really went into depression. I could not understand what I had done wrong. My statistics though say that I had done everything right. So, why was I being rejected at every step? I could not eat or sleep, only cry all day. I was in a very dark place—26 years old already and with no real future. It was during this time, after three big rejections, that a former ICL colleague called me and told me about a sport management company that can help out players like me, who just need a leg-up.”

Taduri Prakashchandra Sudhindra, or a man simply known as Puttu, made the call. The sport management company flew him to Delhi, put him up in a cosy hotel, and promised him the world at a meeting the following day. “There were two men, well-dressed, well-spoken, who told me what they had done for this falana player and that falana player, getting them contracts in this and that T20 league, helping some of them get enough exposure to even make it to the Indian team,” says Sudhindra. “I found myself sitting there and thinking, ‘This is it, this is exactly what I need’. Maybe, all players on the fringes of the Indian team go through a management company like this, so I was almost thrilled that I finally caught the bus. Of course, I signed the contract.”

The premise of the contract was a regular one: they take a commission of Sudhindra’s future earnings, be it from playing for an international T20 league or endorsements that will follow once he has made it famous. “They started to keep in touch regularly, checking up on me and my training, nothing unethical in these calls at all, just very professional and caring as a management company should with its clients. They asked me if I knew any other players who were frustrated like me, so they could help them too.”

“I wish nobody sees such times. I would eat for two hours in a row because that helped with my anxiety, and I would only eat with the TV on to drown out the noise in my head. I wish I had sought therapy then”

Then one day, in late May, ahead of MP’s inter-district T20 tournament in Indore, the meeting took a darker turn. “They said an overseas league was interested in me. But the owners needed to know if they could trust an unknown player like me, so they needed me to prove myself.” How, he asked. The management company said by bowling a no-ball in the first Indore game. “At first, I refused. But they said the management company would not be able to push for me if I did not do it and that I had nothing to lose because it wasn’t a big event. Plus, I would get paid for it. All I had to do was bowl the no-ball and later show them proof of having done it.”

This exchange was what was shown, exactly a year later, in the sting video. Sudhindra settles on an amount and then says that the second ball of his first over in the game will be a no-ball. In the video, the hidden camera footage is followed by the proof—a massive front foot no-ball, surpassing the popping crease by a fair distance. I asked him what it felt like after he bowled that no-ball; after coming through with the fix.

He takes a beat and then says: “Aisa laga ki shareer poora… kya bataoon, chhodiye ab (It felt like my whole body… what can I say, leave it now).” As he says this, he wells up, looking away. “Sorry, it takes me a long time to recover from the memory, so please do not take me there again.”

The management crew stopped calling overnight, but life soon moved on for Sudhindra, for the better. By December 2011, AGO Raipur had reversed its earlier decision and hired him after all. Then, the 2011-12 Ranji Trophy season happened, where he took 40 wickets and topped the charts, which included clean bowling Sourav Ganguly in Dada’s own backyard, twice in the same game. The next three on the season’s wicket-taker’s list, Ashok Dinda, Pankaj Singh and Harshal Patel, would all either go on to play for India or already had. But not Sudhindra, though he would be rewarded for his efforts with a gig at IPL. The lucrative contract saw the sport management firm return with phone calls.

“They asked me to bowl a no-ball in IPL, and offered a bhayanak amount of money for it. I said no. They said alright, and that was it.”

On joining the Deccan Chargers’ camp, Sudhindra and his mates were made to attend an anti-corruption seminar, which he claims was his first tryst with the concept, and it opened his eyes. He had already fallen prey to its playbook, albeit not in IPL. “I thought, chalo, it happened so long ago, nothing to worry about. But I had a bad feeling about what had happened.”

The lurking worry surfaced, and how. “I was at the team hotel in Hyderabad, stretching in my room when a friend called and asked what I was up to. I didn’t understand, so he asked me to turn on the TV,” he says, slumping his shoulders into his chest. “I sat like this all night, watching my face on TV without blinking, unable to believe that any of this was happening. Before I knew it, the sun had come up.”

Deccan Chargers sent two members of their team management to his room, who heard him out patiently but told him he had been booked on the next flight back to Raipur. Kumar Sangakkara, captain of the team then, did not meet him. When he landed, he feared the presence of the press but was greeted only by his brother-in-law and an email from BCCI stating that he had been suspended until further inquiry. He wept in the taxi all the way from Raipur to Bhilai, and didn’t stop weeping for a few days after. His mother, who had gone into a state of shock on hearing the news, would weep with him.

“I wish nobody sees such times. I would eat for two hours in a row because that helped with my anxiety, and I would only eat with the TV on to drown out the noise in my head. I wish I had sought therapy then.”

Therapy, or a version of it, came from his father, brother-in-law, and a handful of friends, who gave him enough love and support for him to eventually try and return to his office job some 20 days later. “When I first joined there in December 2011, I felt like a hero. Everyone would want to talk to me. But now, I used to even eat my lunch alone. They put me in the photocopy room. I used to take printouts all day long. That was at least better than hearing some of the comments passed by the people there.”

Like what?

“To my face, one officer said: ‘Naam na hua toh kya hua, badnaam toh hua’ (You couldn’t make a good name for yourself, but at least made a bad one).

“Even my fiancé had to hear things like that from her colleagues. But she stayed by me. You know, after everything that happened, I tried to call off the marriage, telling Shruti that life as my partner would be very difficult for her. But she said, ‘I will marry only you, come what may.’ Sometimes, that’s all you need to pick yourself up and take the next step.”

Step after excruciating step, he turned his life around. Sudhindra married Shruti, with whom he now has two children. He also became a gazetted officer. Then came the BCCI pardon, which saw him enrol for a position of coach in the Chhattisgarh set-up and was handed their Under-19 team. In his very first year in the role in 2023, he was named the state’s ‘outstanding coach of the year’. Sudhindra wears it lightly.

“See, I know I am not a hero,” he says. “But I also think I am not a villain.”

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande