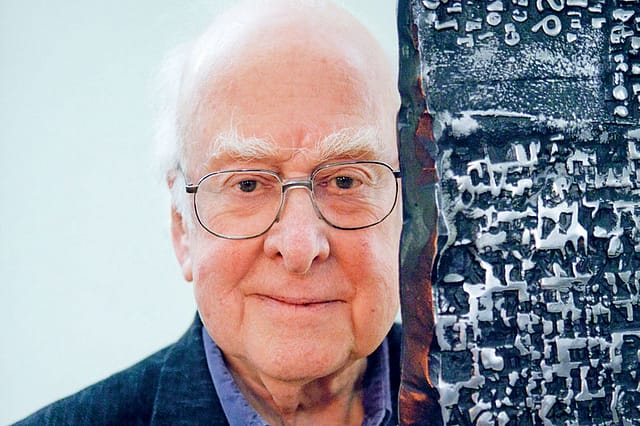

Peter Higgs (1929-2024): Master of Reality

EVER SINCE HUMAN beings developed curiosity to understand the nature of reality, they have been theorising about breaking matter into smaller pieces to arrive at the fundamental unit. All civilisations, from the Greeks to the Indic, came out with their own versions of this. Then the modern scientific age began and the exploration moved from idea to experiment that could confirm the theories. First, there were molecules, then atoms, and then it was found that atoms contained electrons, neutrons, and protons. There were then quarks below them. Every advance seemed to only lead to further complexity. Then it got even more strange with matter itself being a form of energy. Beneath the subatomic particles, other forces and fields were operating and these came with their own particles. There was also a puzzle that this intricate network should collapse into itself and the universe, as we know it, should never exist at all. Peter Higgs, who passed away at the age of 94 on April 8, showed why the matter of the world remains stable by postulating what is now popularly termed the God particle, also known as the Higgs boson. It would eventually lead to him getting a Nobel Prize in 2013, a year after his theory had been shown to be true by the Large Hadron Collider which actually managed to create a Higgs boson. The citation for the prize shared that year with François Englert says it was awarded "for the theoretical discovery of a mechanism that contributes to our understanding of the origin of mass of subatomic particles, and which recently was confirmed through the discovery of the predicted fundamental particle, by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN's Large Hadron Collider".

Higgs' initial growing-up years were often riddled with health issues. He was also precocious, so bright that he was promoted to a class two years higher than his. He learnt mathematics pretty much at home reading his father's engineering books. He continued to be a high performer throughout his schooling and initially specialised in mathematics. It would take time for particle physics to become his chosen field and that too, only after getting a job as a lecturer in Edinburgh. It was in 1964 that he came out with the seminal paper about the Higgs boson. And yet, he wasn't the only one. Particle physics was a buzzing arena and many scientists were arriving at the same theories as Higgs. There was some element of luck in the Higgs boson being associated with his name.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The discovery however did not lead to instant fame. It was only after the large underground colliders began to try to create these particles that Higgs slowly began to figure in the public imagination. As the New York Times wrote: "Interest in the boson came and went in waves. Dr. Higgs's first round of interviews came in 1988, when CERN started up a new accelerator named LEP, for Large Electron Positron collider. One of its main goals was to find the Higgs boson. There was another round when LEP was closing down in 2000 despite claims by some scientists that they had seen traces of the Higgs boson. Dr. Higgs was skeptical. ' They were pushing the machine beyond its limit,' he recalled."

And then came the Large Hadron Collider and finally the Higgs boson being spotted in it in 2012, which instantly made him a celebrity, something that the Nobel the next year only reemphasised. But Higgs remained low-key, preferring his anonymity in many ways. Frank Close, the author of Elusive, writes in it about sitting with Higgs nine years after the discovery with Higgs suddenly remarking that it has ruined his life. Close wrote, "To know nature through mathematics, to see your theory confirmed, to win the plaudits of your peers and join the exclusive club of Nobel laureates: how could all this equate with ruin? To be sure I had not misunderstood, I asked again the next time we spoke. He explained: 'My relatively peaceful existence was ending. I don't enjoy this sort of publicity. My style is to work in isolation, and occasionally have a bright idea.'"