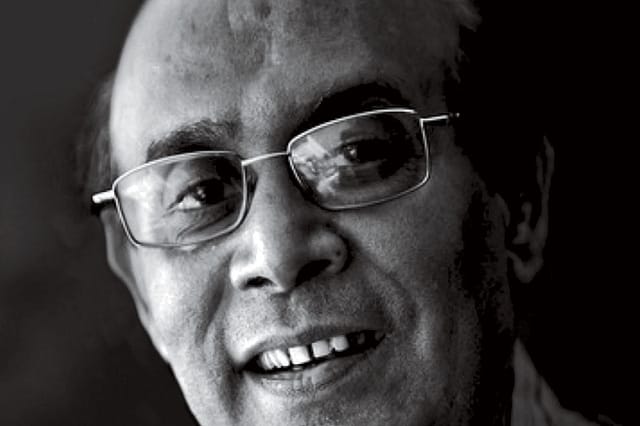

Buddhadeb Dasgupta (1944-2021): A Master Redeemer of the Uprooted

BUDDHADEB DASGUPTA ONCE said he revelled in creative unhappiness, and that nothing made him more complete than his chosen isolation. Through a feature film career that began in 1981 with Dooratwa, he made movies that explored the idea of Bengali manhood. Whether it was the freedom fighter released from prison returning to a post-independent India he didn't recognise in Tahader Katha (1992) or the family man exploring his relationship with his missing father in Kaalpurush (2005), his heroes were always in a state of uprootedness. Blame it on his itinerant childhood as the son of a railway doctor or his own innermost political and personal journeys, Dasgupta was a filmmaker constantly in search of contradiction.

Nowhere was this highlighted better than in Bagh Bahadur (1989), perhaps his most extraordinary movie, where all the binaries come together. Man versus animal, rural versus urban, folk versus modern, man versus woman. In the character of Ghunuram, the city labourer who finds meaning in his life with his annual visit home where he plays the tiger dancer, Bagh Bahadur, Dasgupta sees all our opposites collide. The final wrestling match, between the leopard and Bagh Bahadur, is as much a spectacle that entertains as it brutalises.

From his early trilogy of Dooratwa, Grihajuddha (1982) and Andhi Gali (1984), which explored the impact of the Naxalite movement on the young men of Bengal, through his later films such as Ami, Yasin Ar Amar Madhubala (2007) which examined the rise of the surveillance state and the idea of who is a terrorist, Dasgupta was a director whose only politics was humanism. In the great tradition of Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, his films had a clear-eyed view of the place of man in society, nature and culture.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

His images were startling—birds in and out of cages, much like man himself, in Charachar (1994); an army of dwarfs in Uttara (2000) constantly in search of an alternative world; and two men showing family planning films on makeshift screens against a night-time sky in Swapner Din (2004). His men are poets, wanderers, outsiders, and some would even call them losers. Like the dentist of Lal Darja (1997), always comparing himself to and falling short of the relaxed masculinity of his driver Dinu. Or the two wrestlers of Uttara locked in an eternal bout to prove their might, even as the world around them burns and the woman they are fighting over is violated and killed.

Many of his characters are looking to escape reality and inhabit another world. It could be Ganesh, the driver in Mondo Meyer Upakhyan (2002), who wants to escape an all-seeing, all-knowing job that exposes the ugliness around him; or Amina, the widow in Swapner Din who wants to return to her home in Bangladesh, or the wife in Kaalpurush who cannot wait to escape the monotony of her middle-class life and fly to America. There is a world between the real and mythical and Dasgupta's characters would invariably occupy that space. As Pankaj Tripathi's character says in his 2013 film released last year, Anwar Ka Ajab Kissa: "When I was in college, I thought I would go to the Antarctica, build a home on the North Pole." In Dasgupta's world, every man's ambition could be limitless, far outstripping his material conditions, sometimes offering hope, and at other times providing only tragedy.

For many stars, Buddhadeb Dasgupta's films were where they went to rediscover their acting origins, whether it was Mithun Chakraborty who gave two of his finest performances in Tahader Katha and Kaalpurush, or Prosenjit Chatterjee, who was shorn of all his customary swagger in Swapner Din and Ami, Yasin Ar Amar Madhubala. From Rahul Bose to Paoli Dam, the tributes to him flew thick and fast the day he died because he was one of the last remaining links to a stream of Bengali auteurs whose cinema was self-taught, self-reflective and self-critical. Dasgupta was a regular at film festivals in India and abroad, wearing his laurels—five national awards for best film, among many others—lightly and gracefully.

A teller of stories of marginal people, he was perhaps, like Mithun's character, Ashwini Banerjee, in Kaalpurush, constantly in search of the mythical Kusumpur. May he find it now as he sleeps, perchance to dream forever.