Being and Soundlessness

A meditation on the loss of hearing

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

|

10 Nov, 2023

|

10 Nov, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Soundlessness1.jpg)

The Ear by Salvador Dali

My father-in-law doesn’t like to wear his hearing aids. At 79, he spends two hours driving to and from work in the nefarious Chennai traffic. “I prefer to shut out the street noise,” he says with a smile. I’d gone to the hearing aid lab with him to choose the instruments he liked best. We were shown how to use those skin-toned contraptions shaped like cashew nuts snuggling on top of his ears, silent appendages whispering what to do next. As soon as we got home, he stuffed them in a drawer. They rarely come out of there. He really doesn’t enjoy putting them on. “Sometimes they squeak,” he explains. They resurrect all the irritating sounds of urban reality that hearing loss conveniently shelters him from.

I went with him not only as a gadget nerd but also as the family hearing aids expert, because I’ve been wearing them for more than a decade. I was first diagnosed with hearing loss when I was 27 years old. I’d been living in New York City for six years, and I was about to move back to Italy when I realised I couldn’t hear people very crisply when they spoke. As a young reporter, I wanted to understand what was being said during interviews or in press conferences. So, this was going to be a problem.

I was prone to ear infections, and I just knew there was something wrong with the sound of the world. I’d attended too many loud concerts in small places. I knew a lot about New York nightlife in the late ’80s and ’90s. When I walked out of thumping bars and nightclubs, for a few minutes I’d experience a long hiss in my head. I was also on the phone more than I probably should’ve, in my office on the 21st floor of the Newsweek building on Madison Avenue.

When the doctor told me I was already lip reading, I was taken aback. I’d lost the capacity to capture some high frequencies, he said, especially the ones with consonants like S, T, and Z. Basically, when someone pronounced my last name in a loud environment, instead of “Pizzati,” all I could hear was “Pi_ _ a_i.” Like PI. I needed to become my own Private Investigator to decipher what people said in loud contexts. I had to become Carlo’s PI.

I could see lips pronouncing sounds, but words came off as either silence or as grumblings from a distant cave. The otolaryngologist informed me that I’d need to immediately start wearing hearing instruments. If I didn’t, he warned, the section of my brain accustomed to receiving those frequencies would atrophy. I’d go deaf.

“You might not be able to ever regain your hearing back,” the doctor said, “but if you don’t wear hearing aids, you will increasingly deteriorate your capacity to capture conversations, sounds, music. By the time you’re in your 50s, your deafness might get serious. You can prevent that.” There was no cure, no possible surgery. “Your only hope is to live long enough for stem cell research to find a way to rebuild the dead high frequency receptor cells inside your ear,” the ENT expert concluded. I stumbled out of that office on Fifth avenue in a daze, and for the following 20 years I considered whether or not I should get hearing aids.

At parties and dinners, I struggled to understand what was being said when people covered their mouth with a glass or with their hand, or if they spoke while chewing. In restaurants or at dinners, I would sometimes crane my neck and lean perhaps too uncomfortably close to the person I was trying to understand. What was wrong with me? Hadn’t I heard about personal space?

I’m not sure how many sweet nothings were whispered to me in the most intimate moments, or encouragements to do something which might have been fun, had I only been able to hear the idea instead of blurting out an annoyed: “Sorry, what did you say?”

Once, I visited a blind masseur who touched my neck and said: “You have a hearing problem.” I asked him how he could tell. He touched the side of my neck: “You’re straining this muscle,” he said, pressing on the splenius capitis, “typical of those hard of hearing when they tilt their head closer to the speaker.”

To those who asked why I wouldn’t wear hearing aids, I’d joke that I was afraid: who could guarantee the instruments wouldn’t be hacked, and what if I were subliminally forced to buy IBM stocks just as they were about to plummet? What if these contraptions wired around my ears pushed me to do something I didn’t want to do by whispering subliminal secret commands?

The truth is that I feared that wearing visible hearing aids in my late 20s or 30s, or even in my 40s, would make me look like a much older and disabled man than I wanted to appear. Narcissism kept me away from something science was offering: the possibility of not shutting out from the world of sound around me. Later in life, when my hearing did worsen, I realised I would increasingly avoid crowded restaurants and parties. When riding in the backseat of a car, I’d wander out of the conversation, pretending to be taken by the poetic beauty of the landscape, but actually losing interest in a mangled drumming sound which I could not discern as language.

I could see lips pronouncing sounds, but words came off as either silence or as grumblings from a distant cave. The otolaryngologist informed me that I’d need to immediately start wearing hearing instruments. If I didn’t, he warned, the section of my brain accustomed to receiving those frequencies would atrophy. I’d go deaf

Lips were moving, heads nodding, teeth flashing, eyes winking, heads tilting, as people waited to hear feedback on what they’d just said to me. I could tell them the truth: that I only heard clinking of glasses, rattling of plates, dragging of chairs, humming of traffic, slamming of doors, a jumbled wave of indistinguishable chatter cloaking the words around me. Or I could lie and blurt out: “Yes, great idea!” or “Hmm, oh, I agree,” or more cautiously “Not sure about that one…” I could make people laugh with how often I misunderstood something. Or I could say nothing, sporting the I’m-above-it-all grin that suggested I’d heard this before, although I actually couldn’t tell if I had, because it all sounded like: asterisk, number sign, pound sign, dollar sign, exclamation mark, question mark, and again asterisk, exclamation mark.

A QUEST BORN FROM REDISCOVERING THE LONG-LOST SQUEALING SOUND ON A TRAIN

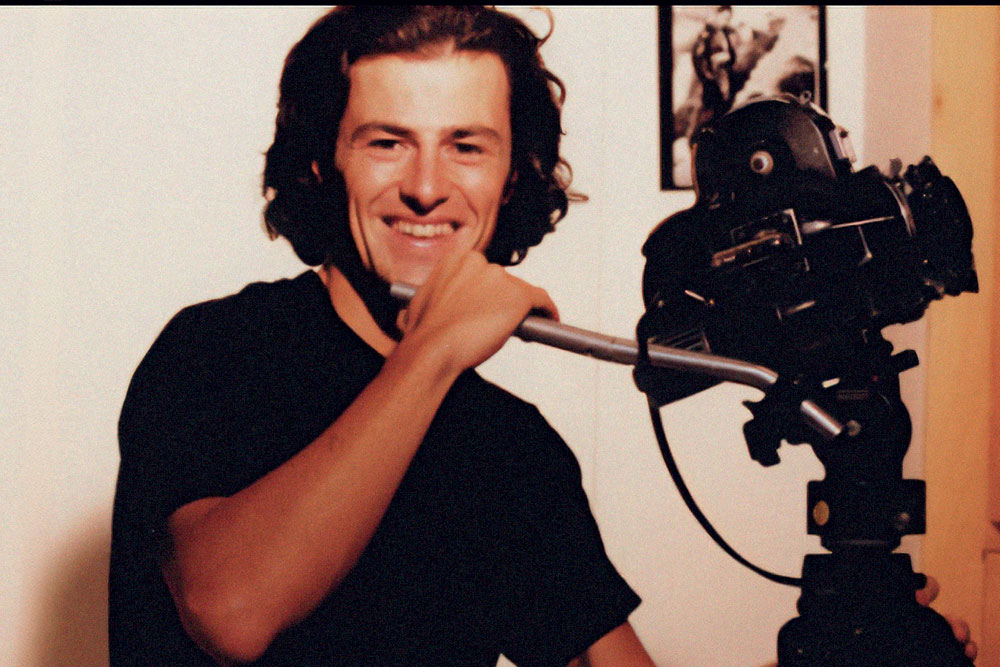

One night, many years ago, I found myself travelling alone with a camera and earphones, while shooting a documentary in Naples. As the train slowed to a stop, I pointed the lenses to the dark nightscape of Naples, floating in the distance. Thanks to the earphones’ amplifying effect, I captured the squealing sound of the badly oiled train wheels right below me. I was moved to tears. I’d just rediscovered a frequency I’d not heard in years. Those dramatic screechy sound was like finding again a dear lost friend, the memory of something I used to know, but I’d forgotten.

Since I had that emotional reaction, I asked myself whether high-pitched sounds are related to a spectrum of emotions, and whether losing the capacity to hear them meant becoming vaccinated against certain types of feelings which I, perhaps, was no longer capable of having. Are we what we perceive? Is our emotional life hampered by sensorial degradations, inevitable with age?

As the senses get duller, so, perhaps, does our capacity to feel and be inspired by the manifested reality around us. Does this give freer rein to anger, stifling tenderness, eating into our emotional cognition? It would explain the existence of a lot of impatient, grumpy dads and uncles roaming around everywhere in the world. Plus, the inevitability of becoming blasé is a known professional hazard for journalists. And yet, I thought there might be something else.

When I was in my early 20s and living in New York, I was a lover of the opera. But I did find it cliche of me to be: 1) Italian 2) living in New York and 3) going to the opera. Really too “Sopranos” of me, too Francis Ford Coppola, too spaghetti and mandolin with a pizza on the side, capish?

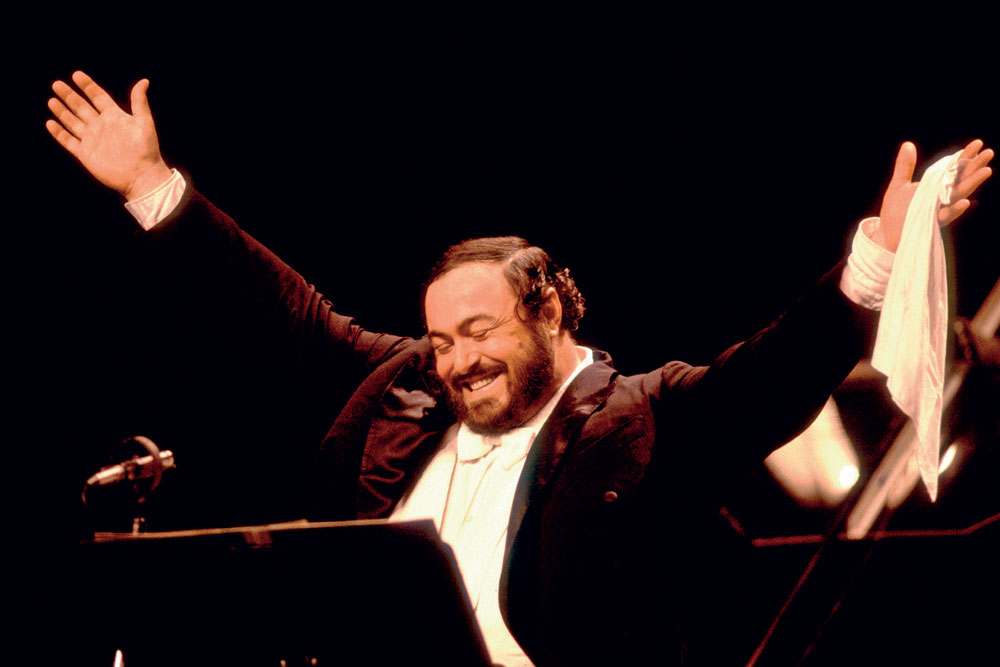

Yet I reacted emotionally to many types of music, including classical and opera. It moved something inside my chest. I rode the subway from downtown to the Metropolitan Opera and bought $10 standing only tickets, knees aching while listening to Luciano Pavarotti belt out his songs. When a soprano reached the peak of her long solo, I would at times feel my throat clench and a tear roll down my cheek. Regardless of the meaning of the lyrics, the sound connected emotionally to me via the ears, through the throat, the lungs and into the heart.

It was as though fireworks made of salty tears exploded in slow motion behind my cheekbones, oozing towards my eyelids, while my lips widened in an ecstatic smile and a deep, long exhalation allowed my clenched neck, tightened shoulders, and stiff back to rest. I felt something soar inside of me: the bliss of musical rapture.

The mind transcribed this as being able to experience a great exaltation through the wonders of the arts—just like when you are inspired by a mind-opening, soul-searching poem, or when you lose your rationality inside a hypnotising painting. You perceive you’re having an experience beyond time and space, you’re elsewhere, drawn by the senses into a diverse interpretation of reality.

In Naples, that night on the train, I realised my capacity to be moved by such sounds had disappeared. I’d lost some shades of the spectrum. I’d also noticed, when listening to music, that the sound of a violin reaching into the high notes would disappear, while people’s faces around me at a concert would still be enraptured in the melody. I understood it didn’t actually dissolve. The sound had simply vanished from my capacity to hear it.

Was my ability to feel certain types of emotion evaporating like that shrill cry, that universal call, that fine musical thread joining humanity in the common experience of musical ecstasy? I decided to investigate. Eventually, I also decided it was time for me to try hearing aids. I think moving to India helped me take this important step.

INVESTIGATING THE EMOTIONAL IMPACT OF SOUND

Hearing involves waves, membranes, vibrations, bones, nerves, chemicals, and electrical signals—a series of complex passages that’s fascinating to unravel. First, sound waves waltz their way into the ear canal and hit a membrane. The eardrum sends those vibrations to three tiny bones with Hobbit-sounding names: the malleus, incus, and stapes. As their Latin names indicate, they resemble a small hammer hitting a miniature anvil pulling on a stirrup-shaped bone. Their job is to amplify the sound vibrations into the cochlea, which is shaped like a snail-shell, as the Greek name indicates, a weird squid-like structure filled with fluid, nestled deep in the inner ear. The vibrations make that fluid ripple: imaging waves caressing hair cells inside this tiny snail-like part of you. Some of these hair cells detect the higher-pitched sounds that people like me lose with either age or overexposure to noise. Thus stimulated, the microscopic tips of the hair cells, the stereocilia, release chemicals that spark an electrical signal which the auditory nerve carries to your brain, so you can hear your mother calling you from downstairs to come have lunch before it gets cold. Complicated, but how wondrous that every single sound we hear goes fantastically fast through this vibrating, liquid, and electrical rigmarole right inside our ears, right now.

The doctor back in New York had told me that because of a congenital issue, or because I exposed them to too many loud sounds too often, or a sum of these two causes, many of my high frequency hair cells had simply been grinded down. Goodbye high pitch. And goodbye emotions. As I dug deeper into audiological and otolaryngologists research, I realised there was some truth to my suspicion.

Pitch matters. To animals and humans alike. A study of 56 birds and mammals by David Huron titled, ‘Affect Induction through Musical Sounds: An Ethological Perspective’ posits that high pitch calls in animals are associated with fear, affinity, or submission. Low pitch calls are associated with threat or aggression. The study confirms that it’s the same for humans. High pitch sounds are associated with friendliness or deference. Low frequency sounds are more threatening, darker.

Once, I visited a blind masseur who touched my neck and said: ‘You have a hearing problem.’ I asked him how he could tell. He touched the side of my neck: ‘You’re straining this muscle,’ he said, pressing on the Splenius Capitis, ‘typical of those hard of hearing when they tilt their head closer to the speaker’

The same holds true for music. Low pitch melodies are perceived as less polite, less submissive, and more threatening than high pitch sounds. Think Wagner. High pitch is more cheerful. Think Mozart. So, the question to myself, as my own Carlo’s PI, now was: is losing the capacity to hear high frequencies making me less cheerful and more cantankerous, since I’m likely to hear more aggressive and intimidating sounds? My wife certainly seems to think so… But had I also forever lost the capacity to feel that pang of emotion I experienced when the soprano hit her high note?

Sound studies do indicate that in opera, heroic roles tend to be assigned to high pitched tenors and sopranos. Villainous roles are mostly assigned to the lower pitched singers like bassos and contraltos. Was my loss of high pitch receptiveness making me less heroic and more villainous, overly exposed as I was to lower pitches?

It would be wrong to assume that the association we have with sounds is universal. It’s all based on personal experience and on what sensorial memory we attach to that sound. Our preferences determine the intensity of an emotional response to various acoustic stimuli.

The sound of thunderstorms feels relaxing to me, perhaps because I associate them with the excitement of my childhood summer vacations in Italy. They tend to scare and induce mild anxiety in my wife, and in all our three dogs. Wind chimes are soothing to me, my wife gets restless listening to them after a while. The drumming sound of rain evokes feelings of freshness and exuberance in my wife, who grew up experiencing India’s monsoons. Nonstop rain makes me melancholic, reminding me of my Northern Italian hometown, which, before climate change heated up the planet, was one of the coldest and dampest valleys in Northern Italy.

A study at Lund University in Sweden indicates what seems obvious: sound and sound environment can affect humans on personal, emotional, and psychological levels. Most people contextualise sound according to what they associate it with. A song you listened to repeatedly after a painful break-up will make you feel maudlin for years. Only laughter is interpreted as universally positive and contagious, unless of course it’s that wide-eyed, insistent, loud grinning Joker kind. That’s universally scary.

Sound does affect emotional contagion on the brain. And music alters moods. According to French otolaryngologist Alfred A Tomatis, the ear is a generator for the nervous system and brain: it can transform stimuli from our environment into energy. High frequency sounds are food for the brain, energising it, stimulating it, enabling it to focus and remember. But it can also manipulate people. Adolf Hitler’s speeches were always accompanied by low frequency drumming, putting his listeners into a hypnotic state. Low pitch can make you want to invade Poland.

The way you perceive a sound impacts your body at a chemical level. Research has shown that certain irritating noises (like those unbearable reverse park beepers) can increase the production of the stress hormone, cortisol, with negative effects on your body and mind. But, again, certain frequencies, melodies, and rhythms (like those soothing massage playlists) can instead help to regulate the stress response system and reduce the cortisol level.

And there it was, amidst the piles of data, the sad truth I had already intuited: “With hearing loss, you lose the emotional impact associated with the sounds you can’t hear or can’t hear well.” In Pierre Sollier’s book, Listening for Wellness, he writes, “With hearing loss, nature walks become less enjoyable when you can no longer hear the faint sounds of flowing water. Music loses its emotional impact when you can’t differentiate specific instruments.”

A STAR-STUDDED ROSTER OF HEARING LOSS

If hearing is indeed more vital to our emotional lives than we realise, then hearing impaired people who lose certain contextual meanings will be marginalised in society. Although this no doubt often happens, especially in cases of total hearing loss, I discovered an impressive list of famous successful hyper-achievers in many fields who suffered from total or partial hearing problems.

The most obvious one of course is Ludwig van Beethoven. He was completely deaf when he created The Ninth symphony. Thomas Edison made all his world-changing discoveries with little or no hearing. Francisco Goya dug into the darkness and depth with his paintings while being hearing impaired. The list is long, from Robert Redford to Whoopi Goldberg and many more. William Shatner got tinnitus, a fastidious ringing in the ear, due to a pyrotechnic mishap while shooting Star Trek. Former US president Bill Clinton was wearing in-canal hearing aids while having adulterous sex in the Oval Office. Harvest Moon, a marvellous album I listened to a lot when I was in middle school, and my hearing had not been damaged yet, was composed by Neil Young with particularly soft tones because he had just been diagnosed with tinnitus and was aware of the damaging impact of loud noises.

In that cold bedroom where I’d play my vinyl LPs and later cassettes, learning English by studying the lyrics, music got me through some pretty humid winters. The late ’70s were a golden era for Italian singer-songwriters who often had a political message woven through their arpeggios, but most often they sang of love, not revolution. They were slow and melodious ballads. Capable fingers plucking guitars felt like they were pressing into my heart, making me imagine a romantic world, creating an enchantment which surrounded my adolescence: it enhanced my already vibrant imagination, it allowed me to create a soundtrack for my plans for a life of travels and adventures, which I actually turned out having. Listening to classical music made me feel like the abstract journey away from my rainy reality was reaching even more elevated, inspiring heights, while putting on the LPs of Sibelius, Schumann, Schubert, Chopin, Mozart. They were transcendental friends. Then, the sharp noises of punk and ska fed into my rebellious streak, jerky sounds smashing like hammers a mildewing reality that the raw, youthful me felt needed to be destroyed, before it could be changed. Music accompanied and provoked my moods, back when I could hear the nuances. And too loud music most likely took away some of my hearing.

I rode the subway from downtown to the metropolitan opera and bought $10 standing only tickets, knees aching while listening to Luciano Pavarotti belt out his songs. When a soprano reached the peak of her long solo, I would at times feel my throat clench and a tear roll down my cheek

But there are more serious issues than losing your connection to music when you no longer hear well. Three years ago, the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care identified hearing loss as the greatest potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia. When you begin to lock out the world of sound and of meaning, things get more confusing. Many other studies demonstrate the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline. So, can treating it reverse the process and reduce the loss? A study by Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders shows that, among those between 70 to 84 years of age, hearing aids could reduce the rate of cognitive decline by 48 percent.

REDISCOVERING THE WIND THROUGH THE PALM TREES AND THE FOAM POPPING IN THE OCEAN

My Indian wife made me. Simple as that. Moving to India I was faced with learning how to comprehend a new accent. Growing up in my teens and 20s in the US, surrounded by English as a second language, getting used first to thick Floridian twang and then to the tough New Yorker street talk, I was already finding it difficult to understand some British accents.

In India, I often found myself begging people to repeat what was being said over the phone, over the counter, in a car, in a classroom, and especially in social settings. Consonants were tweaked beyond my understanding; vowels squeezed out of my capacity to comprehend. I became more reluctant about going to dinners or social gatherings because I couldn’t get what was being said. The music was too loud, the chatter undecipherable. I must’ve looked stupid, or, worse, off putting. I was becoming more solitary. My need to face this issue was then greatly “encouraged” by my wife, who finally made me do the math. Is the fear of appearing old with hearing aids more important that the reality of not understanding a thing? Duh.

A dear friend put me in touch with a hearing lab with good customer care and products. Ranjoth, one of the heirs of the family business, a friendly, turban-sporting Sikh with a strong and clear baritone voice, was and still is so helpful, precise, and available to me and my issues. After the audiological test, he helped programme the channels and bands in my instruments for different hearing contexts: normal, car, restaurant, music.

During my first fitting in his office, with the bustling sounds of chairs scraping and the workers chatting, I could already pick up the sound of traffic whizzing in the major OMR road nearby. A lost crispness was returning to my hearing, but it was only once I left the building that I was overcome by shock and awe.

As the glass door swivelled close behind me, I was astounded by a swooshing sound as I looked up. A tall palm tree. Long branches dancing in the air. Wind, the sound of wind through the palm tree branches! Again, the ancient tears resurfaced in my eyes as I stayed there staring at the palm tree, actually hearing again that acoustic detail I’d lost for so many years. Then, slowly, I began to discern some honking horns in the distance, rising up like tenuous wind instruments of an orchestra, over there on the highway, beyond the trees. All the different sound details re-emerged, outlining an auditory world that had faded away into a duller, rougher, “high-frequency free” world. It was as if, suddenly, colour had returned to colour-blind eyes.

That evening I went for a walk on the beach on the Bay of Bengal. For the entire sunset and into darkness, I sat by the waves, observing in amazement the foam on the surface of the water washing in and out, hearing all the bubbles on the white froth of the sea popping in sequence. It was a natural concert to my cyborg-like ears, a rediscovered world manifesting itself to my renewed listening capacity. I was again in sound ecstasy after so many years of sound darkness.

I now have an app on my phone allowing me to change the volume and adapt to different listening situations in my hearing aids. It feels so futuristic. But I’m not satisfied. I’m now eyeing new hearing aid models. They have rechargeable batteries, more channels, and, most importantly, Bluetooth streaming. You won’t be able to see me wearing them unless you probe the top of my ears to look for those plastic cashew nuts instruments.

I’m planning to invest in those Bluetooth hearing aids. That way I can shut out the world again with the tap of an app. I could be playing Vivaldi while pretending to listen to you, as I sport again that old, familiar, hearing loss attitude of the I’ve-heard-it-all-before grin. You’ll think I’m nodding in agreement, but I’ll be jamming to the Vivaldi beat.

Hearing loss can be useful, if it’s voluntary.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha

Mumbai’s Glazed Memories Shaikh Ayaz