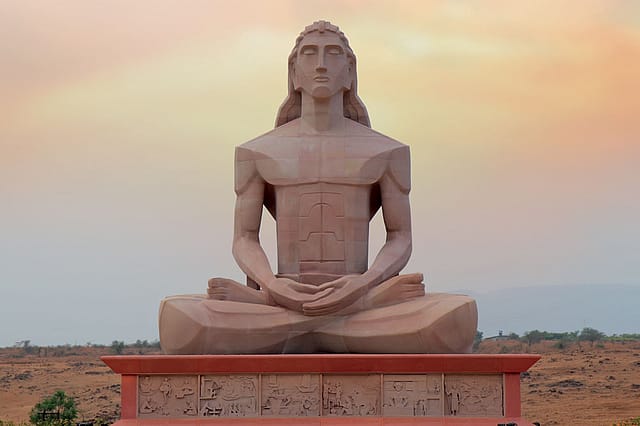

Rishabhdev by the River

HOW DO YOU make a museum for a religion? How do you take a way of living that is practised by 4.5 million Indians and put it within walls? How do you distil the essence of ancient preachings of saints and the essence of the scriptures to make them accessible to today's audience? The Abhay Prabhavana Museum and Knowledge Centre, hailed as one of the largest "Museums of Ideas," dedicated to Jain philosophy and Indian heritage attempts to do just this. Spearheaded by Abhay Firodia, Chairman of the Amar Prerana Trust, the museum was inaugurated by Union Minister Nitin Gadkari in November 2024.

Located 50km from Pune, the museum—dedicated to the "timeless values inspired by Jainism"—is ambitious in both its vision and scale. As a private museum, created by the Firodia Institute of Philosophy, Culture and History (FIPCH), it can heed its own mandate. The museum is essentially the vision of Abhay Firodia (his name even helms the museum and experiential centre's name) and the Firodia family, who have successfully founded several businesses, including Force Motors. Reflecting on the inspiration behind the Museum, Firodia says in the press note, "Abhay Prabhavana stands as a tribute to the profound values of the Shraman and Jain tradition, which form the core of India's ethical and cultural ethos, since millennia. This Museum reflects the principles of Education, Enterprise and Ethics— not just as concepts, but as the real societal values that guide individuals toward a balanced and purposeful life."

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Created over 10 years at a cost of `400 crore, the museum spreads over 50 acres, and is located by the banks of the winding Indrayani River. The location ensures that to reach it you must cross picturesque, harvested fields. The museum is surrounded by agricultural land with the Sahyadri hills forming a faint outline in the distance, nearly obscured by winter haze. In January the fields have turned an unremarkable copper, but during the monsoons the landscape will be veiled in an immodest green.

This museum aims to highlight that even if Jains make up only 0.54 per cent of the total population, the vast majority of Jains fall into India's top wealth quintiles (according to the National Family and Health Survey). With 50 per cent of Jains living in Western India, a location near Mumbai-Pune is only logical. The Jains are a sliver of India's population, and this museum attempts to tell the story of this small but vital community's past and present.

When I arrive on a Friday morning, I am in for many surprises. First, cars have to park a few meters away in a desultory parking lot, and then everyone is shepherded into waiting mini vans. At the entrance, I have to register my presence by providing a state-approved identification. I had been informed that phones and cameras were not allowed inside. But then learn that even women's handbags must be left in the locker. When I am told that I cannot take in my notebook and pen (and that I will be provided with the same) I am ready to schlep back home. Divested of my recorder, but having haggled my way into keeping my own writing instruments, I am allowed to enter.

The museum is divided into various sections, with the first part dedicated to Jain philosophy and metaphysics. Part two focuses on art and culture, architecture and literature. Other sections examine the relevance of Jain values today and the significance of Indic culture (which includes Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism). Depending on one's inclination, one will find different galleries compelling.

The foyer, which is done up all in marble with gold detailing makes an impression with its large glass doors on both sides, allowing for a play of space and light. The standout feature is the eight paintings on the wall. My guide, Navin Kumar Srivastav, assistant curator, who has done his PhD in Jainism at Banaras Hindu University, provides an in-depth explanation for each of the arresting pichwais. Like all worthwhile guides, his inputs add a new layer of meaning to the art and place.

Motifs and figures which appear in these works will reappear many times through the 30-odd galleries. The pichwais are some of the most aesthetically appealing works at the museum. In the first, a Tirthankara (supreme preacher) is seated on a throne in the centre surrounded by concentric circles of humans, animals and vehicles. Another compelling pichwai shows a Tirthankar's mother and her 14 dreams. The mother of Mahavira, Trishala's, 14 dreams (in some traditions there are 16) are another recurring motif in the museum, and the pichwai well illustrates all of them—elephant, bull, lion, Lakshmi, garlands, moon, sun, flag, clay pot, lotus, ocean, chariot, fire and jewels. As I crane my neck to look up at the paintings, two motley tour groups pass me by, and then a group of Jain women monks, easily identifiable by their white sarees, cropped hair and masks. This Friday, the museum seems rather empty, and often I feel there are more safari-clad bouncers than visitors. With a 600-seater restaurant, it is clear that the museum can (and will) host much larger gatherings in the future.

The foyer looks out at the imposing manastambha (Sanskrit for 'column of honour')—a pillar that is often constructed in front of Jain temples or large Jain statues. The 100-foot-tall pillar made from Jaisalmer stone is the central axis around which the rest of the museum is built. Each of the seven layers is intricately carved with figures. Srivastav points out the many interactions between the sculpted ascetics and laypeople. In one relief a masked female monk interacts with followers. In another, the male monk has no mask, but holds a handkerchief by his lap (which he would use while speaking). These precise details reveal the many different ascetic traditions, and emphasise the importance of the interaction between the Shraman (monk) and the Sharavak (disciple) in Jainism. Initially, I am inclined to walk to the top of the pillar, but when I am told that the tour of the museum will take five-six hours, I decide to save on time, and decline.

As we go from gallery to gallery, one learns of the many Jain values and philosophies. The Kaalchakra shows that Jainism believes time is cyclical and not linear. And that time is divided into a period of sorrow, and a period of progress and prosperity. Rishabhadeva or the first Tirthankara (Supreme preacher) of Jainism is shown in different forms. Identified by his long locks of hair which fall to his shoulders, we see him seated in the lotus position in some galleries. He is also shown tearing out his hair, which was an early sign of renunciation. To help humankind, he taught them the skills like Asi (military work), Mashi (writing), Krishi (agricultural work), Vidya (science and arts), Shilpa (making various articles) and Vanijya (trade). Today, the success of Jains as entrepreneurs and businesspeople is still mythologically attributed to Rishabhadeva's lessons.

The Abhay Prabhavana Museum and Knowledge Centre will prove to be especially useful to those who cannot travel or do not wish to travel far and wide in India, as it showcases many Jain monuments. To anyone who has stepped into the Ellora Caves in Maharashtra, stared up at Shravanabelagola in Karnataka or admired the Dilwara Temples in Rajasthan—the replicas can prove as handy reminders, but they do little to recreate the majesty and awe of the original. The replicas are well done, but they will always be a diminished copy of the original. One misses the weathered sincerity of the real which has been replaced by contemporary perfection.

One entire section of the museum is dedicated to "state-of-the-art audio-visuals, animations and virtual reality". With "35 projectors, 675 audio speakers, 230 LED TVs/kiosks, 8000 lighting fixtures," it can all feel like a sensory overload, allowing for little quiet and no contemplation. While these days "virtual reality" might be the buzzwords for many cultural venues, what this often translates into is a Disneyfication of life and living.

Tenets of Jainism, Ahimsa (nonviolence), Anekantavada (pluralism, truth is multifaceted), Aparigraha (nonattachment) are explained through videos. One gallery is packed with eight-feet tall artificial flowers in pink and white and with large hirsute pollen centres. And a video of a bee buzzing from flower to flower is played. The lesson— the bee should take little nectar from each flower, if it takes too much, it will get trapped. Anekantavada, the relativity of views, is illustrated through a large installation of an elephant and a group of six blind men. The earliest versions of the parable of blind men and the elephant are found in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain texts, and they highlight the limits of perception and the importance of complete context.

The LED kiosks provide additional information in Hindi and English about the various figures donning the walls. Curious I try one that is located near a fake body of water. On the kiosk I am asked to choose three bad habits, and three bad emotions. Together these six negative traits form the shape of a boat. And when I press a button the boat sails into the water. For some, these additions to the museum will prove enjoyable. To others it might be rather bewildering.

The personal highlight, after visiting all the galleries, was the "open air heritage walk". The talisman of the Abhay Prabhavana Museum is the 43-foot marble statue of Rishabhdev seated in a lotus position, foregrounded against the Western ghats. Built in an Art Deco style, his cascading locks, sculpted physique, aquiline nose and angular features will evoke certain early representations of Apollo, common in France, which were created in the early 20th century. The nature trail, passing above the river, takes one past other striking landmarks, such as the Plaza of Equanimity and a bonsai garden dedicated to the 24 Tirthankars.

It is perhaps under the blue sky and in the vast open space, skirted by a river, that one can best comprehend Jain values, whether it is nonattachment or pluralism. The Abhay Prabhavana Museum provides something meaningful for everyone. The believer can bask in a space that is built on their principles. And the laity can marvel at how some ancient ethics hold contemporary significance.