Vinod Rai: A Defining Innings

VINOD RAI HAS been in tough places before. His time as the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) was marked by a politically incendiary report in 2010 on the 2G spectrum auctions that indicted the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) for arbitrary and non-transparent allocation of telecom licences leading to a “presumptive loss” of ₹ 1.76 lakh crore. The trial court’s acquittal of the prime accused, including Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam leaders A Raja and Kanimozhi, former officials and corporate bigwigs, in 2017 raised almost as big a storm with Rai receiving flak for allegedly concocting a scam when there was none.

The fact that the 2G scam hurt UPA and helped the Bharatiya Janata Party and its prime ministerial nominee Narendra Modi ahead of the 2014 General Election was the often unstated context to the criticism. Rai stood by the CAG report, pointing out that the court found the inquiry by the Central Bureau of Investigation into the case to be poor. The CAG’s calculations were more than borne out by revenues (pegged at ₹ 67,000 crore) generated by the 3G auctions post the 2G fiasco. Rai was grilled by Congress members of the joint parliamentary committee on 2G during its proceedings in 2011, but he strongly defended the “presumptive loss” as a globally accepted audit procedure (CAG estimated the 2G loss to range between ₹ 57,000 crore and ₹ 1.76 lakh crore). Indeed, the 2G allocations were a shameful abdication of political oversight, with even red flags within the Manmohan Singh PMO failing to attract notice.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Rai’s appointment as head of the Committee of Administrators to oversee affairs for the Board of Control for Cricket in India pitched him into an arena no less challenging, and one where he could not claim hands-on expertise. Perhaps this was a strong qualifying reason, apart from Rai’s reputation of integrity, that prompted the Supreme Court to appoint him after it sacked top BCCI office-bearers for refusing to implement the Lodha committee reforms intended to make functioning of the BCCI and its associations more transparent. No insider could have implemented the changes the court had mandated given the Board’s internecine politics and deeply enmeshed interests. It was also clear that veteran administrators, many of them politicians, were disdainful about the need for any reforms. The Board’s stupendous success in generating multi-billion dollar revenues and the achievements of the men’s team had no doubt bred a certain swagger and even arrogance.

The issue at hand was that the existing Board was unwilling to accept most of the reforms suggested by the Lodha committee, set up after a report into the 2013 IPL betting scandal. Its suggestions such as “one state, one vote” would end the outsize clout some associations enjoyed. It raised valid concerns that some states, such as those in the North East, which barely had any associations, could well become proxies of influential cricketing administrators. Though the argument was not without merit, continued dominance of a set of associations was not a healthy trend either. More troubling for some BCCI bosses was retirement at 70 and detailed provisions on curbing conflicts of interest. The committee also called for a regular full-time CEO and a CFO. The mandate for Rai and others in the CoA (women’s cricket stalwart Diana Edulji, academic Ramachandra Guha and banker and financial expert Vikram Limaye) was to get the Board and its associations to implement the reforms. The new team took up its task in early 2017.

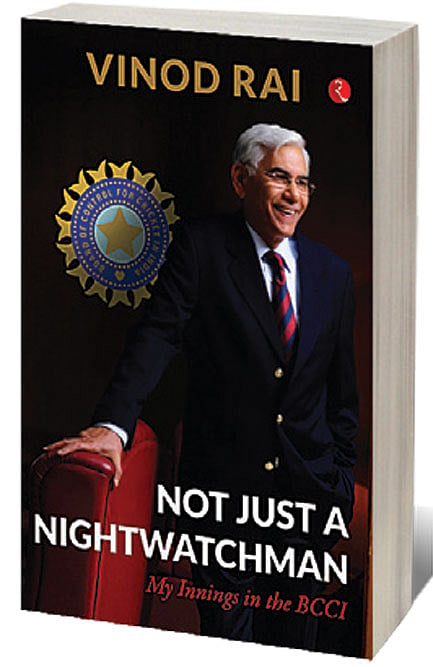

In his very readable account of an assignment that stretched to three years, Rai provides interesting and relevant insights on how the Board dealt with some important issues such as problems with the Board’s financial management (which he feels is still not as good as it should be) and incidents like differences between younger players and veteran Anil Kumble that led to the latter’s exit as coach, an ego clash that marred the women’s campaign for the T20 World Cup in West Indies and the challenge of re-negotiating India’s share of revenues accruing from the International Cricket Council. On the whole, Rai’s recollections carry a ring of authenticity and provide important lessons on the consequences of poor financial oversight and the need to respect players who are, after all, the reason for BCCI’s eminence. Virat Kohli’s reservations about Kumble led to Ravi Shastri being appointed coach in 2017, and he soon introduced a more aggressive approach to the game—one that matched Kohli’s instincts. More recently, the shoddy manner in which Kohli was made to relinquish the ODI captaincy —being informed at the fag end of a call regarding selection for a Test series — was highly avoidable, says Rai. Recalling the Kumble episode, he writes, “It was indeed very prudent of captain Kohli to have maintained a dignified silence. Any utterance from him would have set off a fusillade of opinions. Kumble, on his part, too, kept to himself and did not go public on the issue.” But this did not prevent Kumble from giving vent to his angst that complaints about his “disciplinarian” ways were unjustified. However, the episode underlined a truth: a manager or a coach must enjoy the trust of players and not make the dressing room an oppressive place. The opinion of the captain and the players will always prove decisive, as was evident during current BCCI President Sourav Ganguly’s run in with Australian great Greg Chappell.

The recent women’s ODI World Cup, where again India stumbled at a crucial stage, makes Rai’s recounting of the controversies during the T20 World Cup in 2018 timely. The decision to bench senior Mithali Raj for the semi-final, which India lost, led to a spat between her and coach Ramesh Powar. Statistics suggest India could have used Raj, but Powar and captain Harmanpreet Kaur chose to play the team that won the last game against Australia (Raj missed out due to injury). Raj felt poorly done and Rai tells of how a meeting between her and Harmanpreet helped clear the air. Ironically, Powar was back as coach with Raj as captain for the recent World Cup. Inconsistency undid the Indian team and Raj’s own contributions were patchy. In the 2017 ODI World Cup final against England, a tame run-out had ended her innings just when she might have steered the team to a win. Her place among the greats of Indian cricket is secure (sheer longevity and run records ensure that) but it might be time to look ahead. Rai suggests Harmanpreet, Smriti Mandhana, Ekta Bisht and Deepti Sharma are the future (add talents like Shafali Verma, Harleen Deol, Pooja Vastrakar and Jemimah Rodrigues). It is hard to disagree. While Mandhana is often seen as the poster girl of women’s cricket, denying Harmanpreet her due will be a disservice to Indian cricket and to a player who, according to Rai, knows nothing other than the sport. “Her focus is single-minded, and her conviviality and esprit de corps in the dressing room are truly appreciated,” he writes. The women’s team could also do with a coach of the standing of someone like Rahul Dravid.

Two members of the CoA left early. Limaye was to head the national securities exchange, then hit by a sordid “Himalayan yogi” scandal, and Guha also resigned within months. In Rai’s telling, Guha was frustrated by the slow progress over issues such as conflict of interest. He regrets Guha’s exit as he felt the CoA benefitted from the academic’s knowledge of the game. But he also notes that given the depth of resistance to any change, more time was needed. In fact, issues relating to contracts of some national coaches were soon sorted out. But Guha had left by then. “We had to be resilient and steadfast against these insidious attempts (pushback from interested parties). Throwing in the towel was the easiest way out.” There were differences with Edulji too, as she had strong views on people and issues. But the two found a way to get along, and this in the long run might have aided the cause of Indian cricket.