Modern-day loneliness comes from being on a busy planet, says Kiran Desai

CAN YOU NAME the different kinds of loneliness? There is the isolation of an international student alone on campus during the holidays. The discontent of an unhappy relationship. The despair of being a patient, and a carer facing down a terminal illness. The aloneness of a mother pining for her son. The seclusion of a 58-year-old woman without a father, a husband, a child, a home, a profession. The vacuum a woman might feel trying to make a home for herself and her new husband in a foreign land. The aloneness of an artist or a writer creating works in seclusion. The ivory tower existence caused by fame and success. These are just some of the many lonelinesses that Kiran Desai expertly explores in her new novel The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny (Hamish Hamilton; 688 pages; Rs 999).

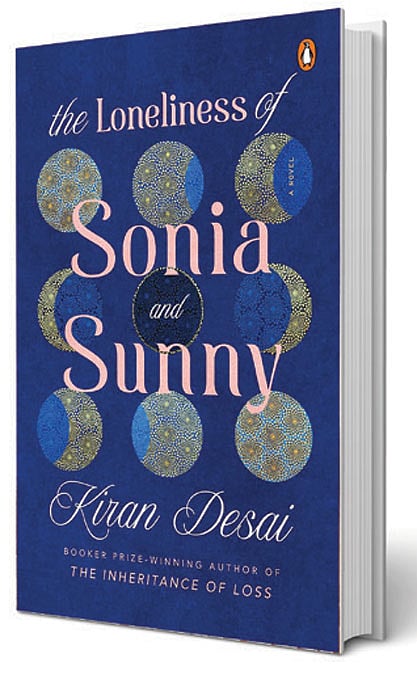

Desai, 54, is best known for The Inheritance of Loss, her second novel, which won the Booker Prize in 2006. The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, 20 years in the making, and of much wider canvas, is on this year’s Booker’s Prize shortlist. The daughter of the novelist Anita Desai, a three-time Booker Prize finalist, one could say Desai was preordained to be a writer. Through the dynamics of home and family, in The Inheritance and The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny she examines the bigger questions of globalisation, multiculturalism, and social and economic inequality. The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is a traditionally big novel both in size and scope. At 700 pages, it spans three generations and moves between India, the US, Mexico and Italy. It has many fascinating characters and compelling plotlines. The tango between Sonia, an Indian student in the US, and Sunny, an Indian copy editor, the ‘will-they’ ‘will-they-not’ suspense unspools the plot. And like all romances, the thrill lies not so much in the foregone conclusion, but rather in how it will all transpire, how will they come together. Their early relationships—Sonia with Ilan de Toorjen Foss, an abusive artist, 30 years older than her, and Sunny’s with Ulla, the daughter of Republicans—mould the protagonists in different and certain ways.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Born in Delhi, and educated in India, the UK and US, Desai has a keen eye for cultural differences and slippages. With levity and acuity, she notes in the novel, “Ulla’s civilization was built upon not snooping and wandering around naked. Sunny’s civilization was based on donning your clothes and listening to every conversation.” But at other times, these same differences are too laboured. For example, when Sunny meets Ulla’s parents at their home in Kansas nearly all topics are off limits for the fear of offending the other. Both sides are soon enough exposed to the fact that “Ulla’s parents and Sunny knew so little about their respective landscapes that they struggled to find things to say that could not be misinterpreted or did not reveal their ignorance.” After a while, these differences seem theoretical rather than actual, and at times one can’t help but feel one has read the same in other diasporic novels.

On the other hand, the women characters in The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny are hugely memorable, whether it is Mina Foi, Sonia’s aunt who finds community finally in a convent, or Sonia’s mother who comes into her own in the Himalayas after she spurns domestic responsibilities. The men often seem like foils to the women, they all seem capable of intense cruelty even if they can be tender on occasion. The predisposition of men often seems to be anti-women. After a horrific incident with a tour guide, Sonia contemplates this hatred. “Madan didn’t know her, but he hated her. He was a stranger, but his anger was familiar. She recognized it, it was ubiquitous, it was in the air, it was in every man she’d ever met, that resentment. It was in her father, in the dinner-party uncles, in Ilan, in Sunny…It was the anger of being countered, refused, surpassed, denied, not adored enough—or simply ignored, because hell hath no fury like a man who is not the centre of attention.”

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is the kind of novel that lends itself to cinematic adaptation, given its high drama, volatile characters and the scope of events from the destruction of Babri Masjid to 9/11 to the riots of Ahmedabad. It will appeal to those who enjoy books that open with family trees, which lay out the vast cast of characters, including pet cats and dogs. The sprawling cast keeps one’s attention, as Desai often creates those on the sidelines most vividly. It is an epic romance, which sketches the web of family and country, belonging and nationhood. With Sonia and Sunny, it is ultimately a coming-of-age story which grapples with creativity and ambition, loneliness and its antidote, love.

When Desai and I speak online she is at her home in New York. Next to her sits an intricate little statue of Krishna playing an invisible flute, which once belonged to her father, and which serves as an apt metaphor for an artist and her creation. Her home is in the diverse neighbourhood of Jackson Heights, famous for its Nepali momos, Bangladeshi biryani and storefronts selling gold. It has in the past been hailed as “the most culturally diverse neighborhood in New York, if not on the planet.” It seems a befitting location for an author whose writerly concerns have always honed in on questions of migration and belonging, foreigner and native.

The book’s title came to her early on and helped steer its course, keeping the focus on Sonia and Sunny. She explains the novel’s genesis, “What I was exploring is modern day loneliness because it is a particular kind of loneliness that comes from being on such a busy planet, of all of us being mixed up together and the world supposedly growing smaller all the time. While I think the divide between us simultaneously is growing bigger, I was trying to write about that unknowingness, that space between us. As you can see from Sonia and Sunny—that’s how the book is structured—it’s talking about that white space, all the rifts between us, the focus is on that emptiness.”

WITH THE NOVEL out in the world, Desai is now slowly trying to figure out what next. She has spent the last two decades dwelling with Sonia, Sunny, their parents, lovers and friends. Every day she would go to her desk and write till the evening. She adds, “The thing is, I really do love to write. It may be difficult, but it’s a joy to me. So, the day I’m not working is always sort of an empty day.” Over the last two decades, Desai’s life has changed just as her characters grew and morphed. While her father, Ashvin, was alive she would return to her childhood home in Delhi every year. His death in 2008 frayed her relationship with India. She still has family and friends in the country, especially in Hyderabad, but her anchor has been unseated. Part V of the novel titled ‘Funny Flat Smell of Home’, is a direct reference for Desai’s travels back to Delhi and the metallic taste of that first sip of water. As her visits to India reduced, she says, “I thought this is the last time, I’ll really be able to write deeply about India.”

As a fervent notebook keeper, Desai succeeds in writing deeply about India, the US, Italy and Mexico in the novel. Here, she can conjure up New Delhi and New York, Goa and Landour because she wrote those parts while she was located there. Goa comes alive in its “small shops in the crevices of banyan trees with sparse shelves of candles, pencils, soap, country eggs speckled with chicken droppings.” Thanks to the diaries, and now the novel, even 15 years later, she can still ‘see’ Goa, whether it is the street dogs with kind eyes or the lush landscape. She says, “I did not use a landscape that I was unfamiliar with because I just think that especially if you’re writing about other countries, other places, you have to try and get it right.” Immersed in the novel she hasn’t maintained her diaries over the last few years and is now in a slight panic over that omission. She hasn’t chronicled Covid, the lockdown and other such momentous happenings, and now regrets not keeping notes, as it might make the process of writing her next book harder, as it might make the process of writing her next book harder.

Desai at one time had written over 5,000 pages for The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny. She would print out sheaths of pages and carry them with her, whether she was meeting her mother in Cold Spring, New York, or travelling in Mexico. Today she has bins full of pages tied with string. To trim the novel entailed not only deleting large chunks of text but also then resettling the entire tone of the book. Calling the process, “very hard,” she elaborates, “It was extremely hard because I kept thinking that some of the things that I was exploring in those pages had a direct and important link that they actually had something to say about the pages that remained. I was really interested also in talking about the rise of nationalism in India, the beginning of those conversations, the change in tenor in the conversations in living rooms, the beginning of those shifts that at those times seemed quite subtle until they weren’t subtle at all.”

While the editing and rewriting process proved challenging in their own way, Desai had one unique advantage and that was of her mother as both reader and editor. Anita has been the first reader of her daughter’s three novels. (The Inheritance is dedicated to Anita; ‘To my mother with so much love’.) Anita reads Desai’s work with care and consideration, not slashing text, but making careful notes on what works and how certain aspects might be reworked. Desai says, “I have become extremely grateful that she is taking the time. That I have her eye on my work because I trust it so much. And I know she is a very unsentimental reader, and I know she is a very, very clear-eyed critic. She gives me a sort of map.” Desai has been greatly influenced by her mother’s bookshelves and reading habits.

In The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny Sonia, a keeper of notebooks, too gets her reading habits from her mother, who imbibes it from her German father. Desai has vivid memories of reading at the Delhi Public Library, the British Council Library and the many bookshops of Khan Market in the capital. During the summer holidays she would read at libraries in Landour and Ranikhet and was always fascinated by the books dating back to the British Raj, which had detailed descriptions of Himalayan flora and fauna. And there were also wondrous children’s books like Satchkin Patchkin that mysteriously arrived home.

Having grown up in a world of letters, Desai could take for granted a creative and rich interior life. In The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny she astutely interrogates the costs of ambition, the collateral of fame and the meaning of success through the artist Ilan. The veteran artist might introduce Sonia to gallerists in New York and help her land a job, but reading about him in a post-#MeToo era can only raise a reader’s hackles. He tells Sonia he loves her and needs her, but treats her like an unpaid maid, even telling her to get down on her knees and promise everlasting obedience to him. He even spits toothpaste foam onto her face. He is an artist in love with himself, convinced of his own genius who treats women like disposable toys. Through Ilan’s character, Desai wanted to examine not only the ‘monster artist’ but also today’s obsession with success and fame. She says, “It is a repetitive character. And yet it’s something that keeps on happening and the world keeps churning out these monsters, or the monsters keep churning out the world as we know it. What was interesting to me with the character of Ilan is this monstrous fame. And my thinking is that also is its own kind of loneliness. Our world is now more and more fame focused. There’s this extreme emphasis on fame, following famous people, on celebrity, and everything becomes linked to a personality and a person. But, the book is secretly structured according to who is in whose gaze and who is in whose purview, whose story is controlled by who. And of course, there are artists and artists. There is Ilan, and then there’s also Sonia’s grandfather, who’s a very different kind of artist. One who wants to vanish into his work and lose his sense of self, and the other one who is building a monument to himself at every moment.”

Through Sonia’s grandfather we meet Badal Baba, a talisman of sorts for both the novel and for Desai’s writing, and a nod to how the uncanny can often tie together reality.

I finally ask Desai if writing can alleviate loneliness. With a gentle smile she replies, “I think as a writer you have to be lonely.” She adds, “I know loneliness in all its different forms, the difficult bits, but also the sustenance of it, the quiet of it, sometimes it does also feel so glorious.”