Reimagining the ultimate devotee

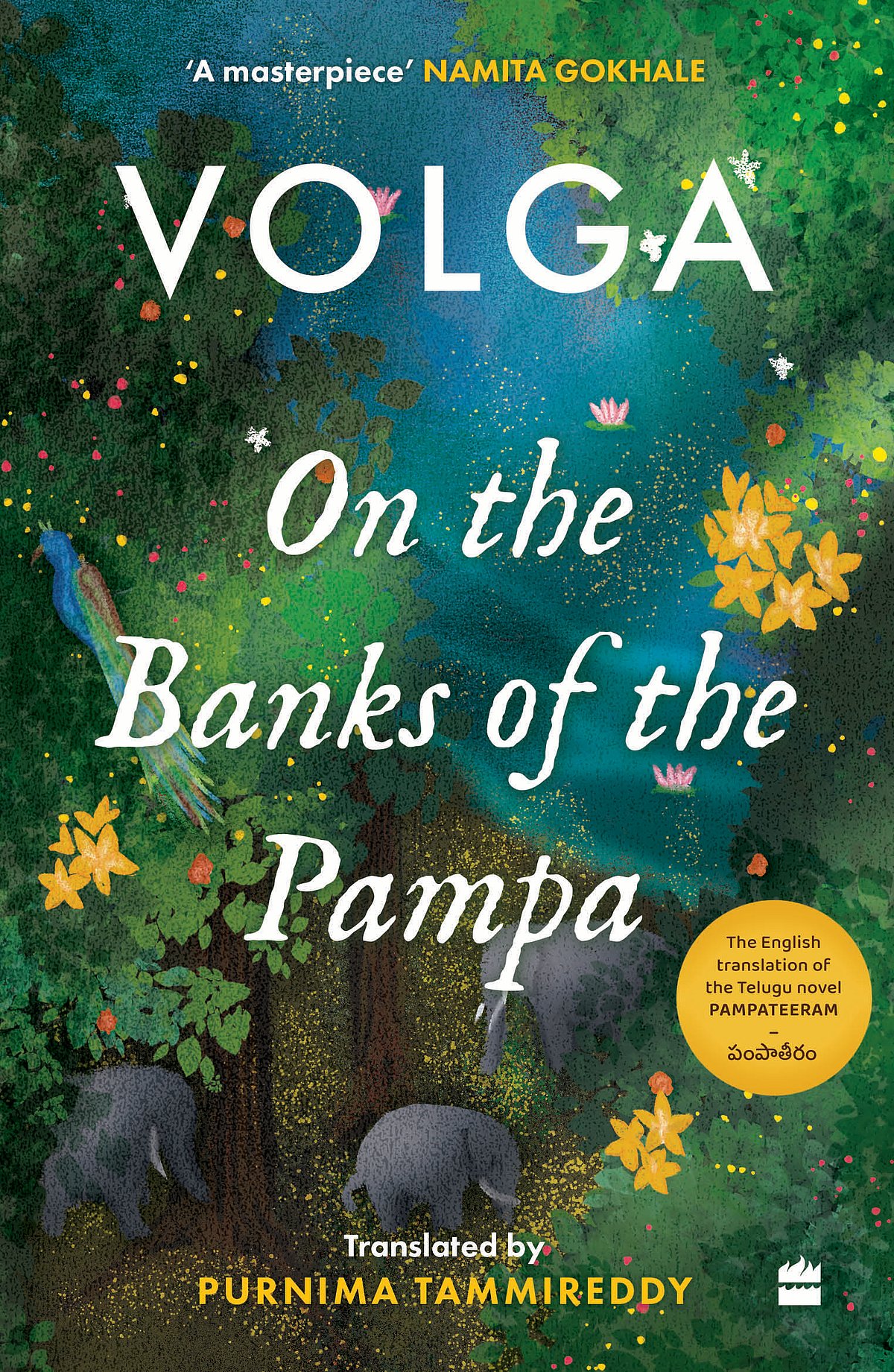

Most are familiar with Sabari’s story in the Ramayana. Ram encounters her in his exile in the forest. When she greets him, she gives him berries she sampled to see which were the sweetest. Understanding her ignorance, Ram forgives the taboo and accepts the offering and her devotion. The award-winning Telugu author and translator Volga reimagines Sabari’s role, opinions and actions in her new book On the Bank of the Pampa, translated by Purnima Tammireddy. This is the concluding volume of Volga’s trilogy of epics with a feminist retelling.

The book is mostly from Sabari’s viewpoint, and she is more than a brief anecdote in Ram’s life, and more than the ultimate devotee. Ram himself is a shadowy figure, appearing at the end. Sabari is an aranyavasi, coming from traditional forest dwellers. She is an ascetic, living in harmony with nature with the rishi Matangi Muni in the forest ashram. As a child, Sabari, along with her parents, was enslaved by an unnamed kingdom. Throughout the book, Sabari’s experiences are used to critique mythical kingdoms (referred to as ‘rajyams’), as she believes them to be exploitative and grasping, destroying forests and enslaving its inhabitants for ‘civilisation’.

The book describes, “The invaders were from a city on the other side of the forest, where they had been living for many years. However, their population had grown exponentially... The only solutions they could conceive for all these problems were to occupy the forest, expand the city, convert parts of the forest into arable land and divert water from the rivers to the streams for irrigation.”

Given Sabari’s torment at the hand of a rajyam, Volga stresses that Sabari’s admiration of Ram is not because of his royalty or even his reputation as a demon-slaying hero, but because her knowledge of him is incomplete. Sabari thinks he voluntarily gave up his claim to the throne to live in the forest, so she

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

believes he is an idealistic figure who rejected the rajyam, and so can inspire real reform for the marginalised. She doesn’t realise he was banished by his father and he complied out of filial duty.

The catalyst for Ram being banished is the same across versions of the Ramayan. Some myths even have the Vedic gods orchestrate Ram’s exile so he can defeat the demons in the South. Volga has reimagined the reason for Ram’s exile. Here the rishis Vaishashti and Purishotam plot to have Ram bring the southern states and its people (daishyas) brought under Ayodhya’s dominion as the southern numbers are too great to challenge outright. In her book, Kaikei and Mantra are made public scapegoats, instead of petty women who wanted Ram disinherited so Bharat could be king. Volga uses her narrative to emphasise that the feudal kingdoms in the epics, with just, heroic kings, prosperous subjects, and idyllic societies were myths. War, conquest, slavery, hierarchies and discrimination were necessary to maintain ancient feudal structures. Sutapa, from Ayodhya, is dazzled at Ram’s heroic stature, and believes in the myth of his being a saviour. His brother asks him wearily, “Do you think anything will change when he is king?” He is one of the few city characters to voice his sceptism. The experiences of the low caste sage Matangi Muni is also used to explore how the Brahmins perpetuated the caste system and the rajyam to stay in power. Much of the book is written through Matangi and Sabari’s memories. The plot moves slowly through the present, showing the aging Sabari’s anticipation of Ram, believing he has renounced the world.

In Volga’s other novels of her trilogy, The Liberalisation of Sita, and Yashodhara, the women are also no longer patient satellites in their men’s lives. Sita’s ultimate fate is not seen as the final tragedy when she is unable to bear more injustice, but as a choice giving her freedom. Yashodhara is more than the long-suffering wife of Prince Siddharth after he became Buddha. Volga reminds readers, that as one of the first women to be ordained as bhikkhuni, Yashodhara had more agency than many remember.

Volga reimagines these women, and Sabari as introspective, assertive even radical individuals. The forest, like the rajyam, are major secondary characters in the novel. On the Banks of the Pampa is a layered, deeply political novel, which deconstructs many preconceived notions about mythical kingdoms. Volga’s message of cruel and exploitative rajyams, and the idyllic peace of forests is at times repetitive and heavy-handed. The pace of the novel is uneven, and much of the dialogue is anachronistic. However, it is still an unforgettable and thought-provoking novel.